Feb 11, 2019

Treasury to Investigate Bond Holdings of Venezuelan Banks

, Bloomberg News

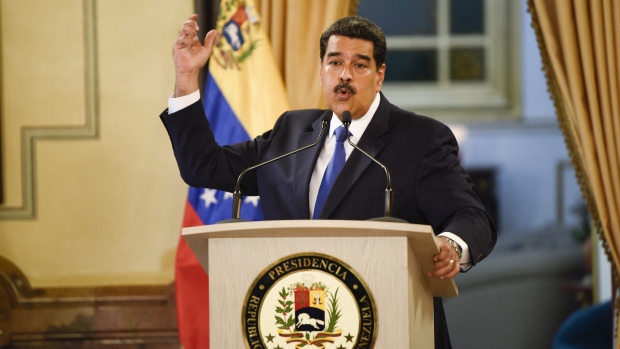

(Bloomberg) -- The Treasury Department is seeking to unmask the accounts Venezuela’s state-run banks could be using to sell bonds and raise money for Nicolas Maduro’s regime, according to six people familiar with the matter.

Treasury officials told investors that the U.S. ban on Venezuelan debt trading is in part designed to prevent sales that could benefit the authoritarian government, according to the people, who asked not to be identified because they weren’t authorized to discuss the matter. The restrictions are so sweeping because at this point Treasury can’t be sure which transactions might be providing money to the regime or high-ranking officials, they said.

Venezuela observers have long suspected that billions of dollars of the country’s bonds, most issued years ago, are held in local accounts controlled by individuals connected to the administration or by state-owned entities like the central bank, Banco de Venezuela and the Economic and Social Development Bank. Such notes came under scrutiny in May 2017, when Goldman Sachs Asset Management bought $2.8 billion of securities from the state oil company through a broker, providing cash to a financially strapped regime carrying out a deadly crackdown on street protests.

The Treasury met with investors early last week to explain the scope of the sanctions and hear concerns. About $60 billion of Venezuelan bonds are in default.

Officials have been reviewing intermediary accounts from Miami to Panama City and the Cayman Islands to look for connections to suspect accounts, the people said. While there’s optimism recent sanctions that largely prohibit trading in Venezuelan debt have been effective in cutting off sales that could benefit the government, the ban would need to be re-evaluated if a political transition takes longer than expected, the people said.

The U.S. and dozens of other nations have backed National Assembly leader Juan Guaido as interim president, and officials sees cutting off funding as a critical component of pressuring Maduro to leave office peacefully.

As of last year, roughly $17 billion worth of Venezuelan notes were in local accounts, according to New York-based brokerage firm Torino Capital.

A spokesperson at the Treasury Department declined to comment on any meetings related to Venezuela.

“Is it a crime or illegal for public banks to sell their securities in the secondary market?” Simon Zerpa, Venezuela’s Finance Minister, said in an interview. “The question comes with the stain that we cannot seek resources to help the economy of our country work.”

Venezuela’s benchmark bonds suffered their worst week in more than a year last week as trading restrictions sapped demand for the defaulted debt. The $4 billion of government notes due in 2027 tumbled 3.7 cents to about 30 cents on the dollar, according to price quotes compiled by Bloomberg. Investors had bid up the debt earlier this year as Guaido and his allies gained momentum in their efforts to oust Maduro from power.

--With assistance from Jose Enrique Arrioja.

To contact the reporter on this story: Ben Bartenstein in New York at bbartenstei3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Rita Nazareth at rnazareth@bloomberg.net, ;Jeremy Herron at jherron8@bloomberg.net, ;David Papadopoulos at papadopoulos@bloomberg.net, Brendan Walsh

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.