Dec 1, 2020

Treasury Yield Spike Risks Sparking Domino Effect Across Markets

, Bloomberg News

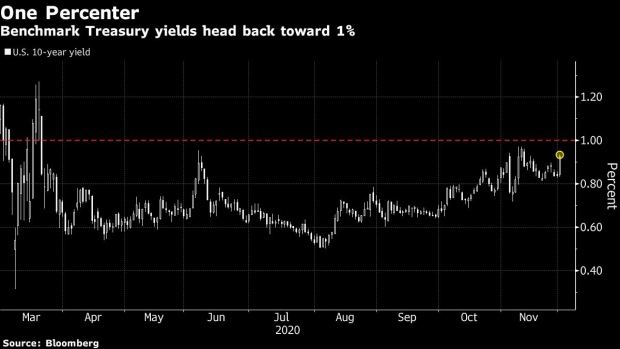

(Bloomberg) -- After a late-November lull, 10-year Treasury yields are on the march toward 1% again, leaving investors to contemplate what that might mean for different markets.

The level of the world’s global bond benchmark -- which traded at 0.92% Wednesday -- influences a host of investment decisions from equity sector selection to emerging-market currency choice to duration and credit bets. The reason yields are moving is even more important, as are expectations for where they will end up.

“A range of 1% to 2% is certainly possible and it would have wide implications across everything from emerging Asian currencies to commodities,” said Vishnu Varathan, head of economics and strategy at Mizuho Bank Ltd. in Singapore. “It’s likely a matter of when -- not if -- yields will climb.”

On Tuesday, 10-year yields saw one of their biggest spikes of the year as renewed stimulus hopes added to optimism over progress on coronavirus vaccines. Benchmark yields have tripled from their March lows on bets of a global economic recovery and a Bank of America survey last month found a record 73% of investors expected a steeper yield curve.

Here’s a look at what higher Treasury yields could mean for other asset classes:

Skyrocketing Stocks

One of the clearest winners from higher Treasury yields could be equities, particularly those most exposed to a reflating economy. The MSCI AC World Index is already trading at a record and an investor rotation to cyclical shares such as industrial and materials names accelerated last month.

“To the extent yields rise, it’s likely to be on higher inflation expectations,” said Andrew Sheets, cross-asset strategist at Morgan Stanley. “Periods where yields were rising and the yield curve is steepening -- those are some of the best periods for the stock market.”

JPMorgan Asset Management is more cautious on how far a Treasury selloff could go, but “the most likely scenario is that yes, equities will go further” in the event of higher yields, said Patrik Schowitz, global strategist at JPMorgan Asset Management in Hong Kong. “There’s more air to the upside in value stocks.”

No Fear For EM

While higher Treasury yields have traditionally triggered a selloff in emerging market bonds and currencies, 2021 may prove otherwise, according to strategists. Because the recent climb is clearly linked to improved economic prospects, it’s also positive for asset prices in developing nations, said Khoon Goh, head of Asia research at Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd. in Singapore.

“A break of 1% in the 10-year U.S. bond yield is unlikely to cause too much stress for emerging markets,” Goh said. “With the Fed expected to keep policy very accommodative for some time, there is nothing for EM to fear at this stage.”

Case in point is Indonesia, whose 10-year bond yield plummeted to a 2018 low last month as investors snapped up higher-yielding and growth-sensitive assets. The rupiah is also Asia’s best-performing currency over the past month, rallying more than 3.6% against the dollar.

Gold Hold

The outlook is a little less certain for gold.

If a rise in Treasury yields to 1% or higher “is due to a reflation trade, then inflation breakevens -- gold and gold miners, commodities, will do well usually,” according to Societe Generale SA strategist Sophie Huynh.

But further gains in yields might also hurt the yellow metal as demand for haven assets wane, according to Ken Peng, head of Asia investment strategy at Citigroup Inc.’s private-banking arm.

“Say we go to 1.5% on the 10-year yield, then you’re likely to see gold below $1,800, closer to $1,700,” Peng said. Gold traded around $1,810 on Wednesday.

Credit Bonanza

Like equities, the credit market may also stand to gain from higher Treasury yields.

Debt investors have been clamoring for longer-term U.S. corporate bonds as stimulus spending bolsters risk appetite, sending spreads on notes maturing in 10-years or more to their tightest since February.

Credit spreads should remain tight as long as the move higher in Treasury yields is due to a reflation trade, SocGen’s Huynh said. But “if bonds start to sell off to due expectations of an increasing net supply of Treasuries, that could start to be quite negative for any leveraged parts of the economy first,” she added.

Fed Reaction

Still, much will depend on the response of the Federal Reserve to any spike in U.S. yields, particularly amid the ongoing debate on its asset purchase program and expectations it will let the economy run hot.

The Fed is currently buying about $120 billion in Treasuries and mortgage-backed bonds every month, partly aimed at lowering borrowing costs for businesses and households.

Longer-term bets around Treasuries and their ripple effects on other asset classes may hinge on “how the Fed communicates,” said Citi’s Peng. “There’s a huge amount of inertia in terms of positioning that’s prevented higher yields -- that’s fine when we’re in a recession, but not when we’re in proper recovery mode.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.