Jan 31, 2023

Trump-Backed Dream of a Venezuela Coup Dies With Maduro Gaining Power

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Juan Guaidó was feted like a rock star when he emerged as the fresh-faced leader of Venezuela's opposition. He met world leaders at Davos, received a standing ovation at Donald Trump’s State of the Union address and led protests in Caracas that drew thousands of supporters screaming his name.

Four years later, the US-backed effort to replace authoritarian President Nicolás Maduro with Guaidó has ended in humiliating defeat. After ousting Guaidó, the pro-democracy movement installed a doctor living in exile in Spain as its nominal head. Now, the opposition is pinning its hopes on the 2024 presidential election.

The gambit marks a return to a strategy that has mostly failed over the past 25 years. Even if the opposition had a strong candidate — it doesn’t — Venezuela’s elections have long been shadowed by allegations of fraud and voter intimidation, making a pro-democracy victory implausible at best.

“It’s a moment of deep fracture” for the opposition, said Michael Penfold, a professor at the Institute of Advanced Studies in Administration in Caracas. “The dilemma is if they are going to be able to rebuild themselves.”

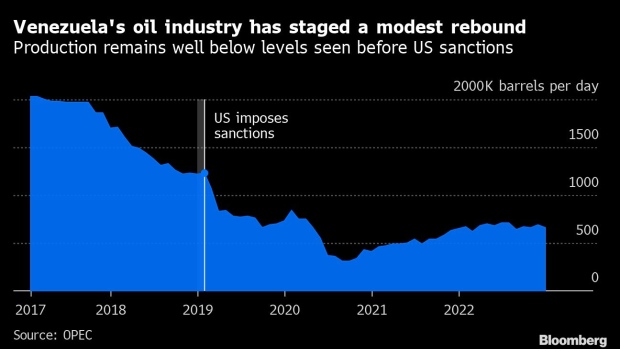

The opposition’s implosion comes at a critical juncture for Venezuela. In the runup to next year’s election, 60-year-old Maduro is as strong as ever. He’s restoring relations with other Latin American governments. In an about-face, the US has lifted some sanctions on his regime, allowing Chevron Corp. to pump more oil in the once-mighty petrostate.

Dozens of foreign governments had gifted Guaidó, 39, control of Venezuelan state-owned assets abroad, including refiner Citgo Petroleum Corp. and $1 billion of gold held at the Bank of England. With his removal, they’re closer to falling back into Maduro’s hands or into those of creditors. While the country’s economic crisis has eased, triple-digit inflation endures and there’s no end in sight to the exodus of millions of Venezuelans fleeing poverty and political persecution.

The opposition-led National Assembly's new president, 61-year-old Dinorah Figuera, is one of three exiled lawmakers elected this month by legislators. Leaders living outside the country, lawmakers reasoned, would be less likely to face harassment from the government. Still, an arrest warrant has been issued for them and the homes they left behind in Venezuela were recently raided.

For Figuera, unifying behind the maximum-pressure strategy was long ago “exhausted,” she said by phone this month from Valencia, Spain, where she makes ends meet by caring for an elderly woman while awaiting a Spanish medical license.

“The route is electoral. That’s the path we’re pursuing,” she said.

The opposition is pushing for negotiations with the government to win electoral guarantees, such as the presence of international monitors and the lifting of bans on candidates. The two sides last met in November in Mexico, however, and a new round of talks has yet to be scheduled.

Guaidó’s ouster leaves in limbo billions of dollars in Venezuelan government-owned assets held overseas. A five-member council appointed by the opposition will now be charged with overseeing that wealth, including fending off lawsuits from plaintiffs pursuing about $40 billion in claims.

For now, US and European sanctions protect some of those assets. But governments are under pressure to drop those protections, putting the opposition’s ownership of them at risk, said Yon Goicoechea, a member of the assets council and Guaidó's former adviser in international cooperation and assets protection.

In the case of Citgo, a US judge has already ordered a court-appointed special master to organize the sale of shares of parent company PDV Holding Inc. The sale is only being held up by Washington’s protections, which come up for renewal in April.

It’s a stark reversal from the early days of 2019, when Guaidó declared himself interim president and — with Trump’s blessing — formed a shadow government replete with staff and ambassadors. But after failing to win over Venezuela’s powerful military and deliver on his promise to quickly unseat Maduro, his popularity began to ebb.

Guaidó’s fall from grace is a victory for Maduro, who took over from the late firebrand Hugo Chavez a decade ago.

With the opposition’s collapse, Maduro is poised to continue winning back legitimacy on the international stage. Though it doesn’t officially recognize Maduro, Washington sent envoys to negotiate with him last year, carrying out prisoner swaps and lifting sanctions that have allowed Chevron’s oil output from Venezuela to jump 80%. Closer to home, newly elected leftist presidents in Latin America have been restoring ties with his government.

“Someone now has to pick up the broken pieces in Washington,” Maduro said following the vote to remove Guaidó. “The Trumpist policy against Venezuela of assaulting the public powers, replacing them, appointing a president, a national assembly, a judicial power, from abroad — it failed.”

The US continues to recognize the opposition-led National Assembly as the “only remaining democratically elected institution in Venezuela today,” Ned Price, a spokesman for the State Department, said earlier this month.

“We support the Venezuelan people in their desire for a peaceful restoration of democracy through free and fair elections,” Price said.

Guaidó has called his removal “unconstitutional,” though he says he will abide by the decision. In a shift from years past, when he led boycotts of elections, he’s expected to compete in crowded primaries the opposition plans to hold this year.

But he faces long odds. Support for Guaidó fell to 12% in December from around 60% in January 2019, according to Caracas-based pollster Delphos.

“In reality the support was not for him, the support was for the hope of the possibility of change,” said Félix Seijas, head of Delphos.

Stripped of his status as interim president, Guaidó is more vulnerable to being arrested in connection with investigations the government has opened against him. He’s not allowed to travel outside of the country and is barred from competing in elections, though the opposition is pushing Maduro to lift those bans.

“I understand exile perfectly, but my decision is to stay here in Venezuela, because the battle field must also be defended,” Guaidó said in an interview Jan. 12.

In a speech on Thursday, Guaidó acknowledged that under his leadership, the opposition had failed to achieve its goal of ousting Maduro.

“Ending this dictatorship is a task that’s still pending,” he said. As he spoke from a Caracas stage near the site of massive street rallies he’d led just few years ago, a power outage plunged the theater into darkness.

--With assistance from Nicolle Yapur.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.