Sep 11, 2019

Trump Brags He’s the ‘King of Debt,’ But He Doesn’t Get It

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Financial markets at this point ignore just about any tweet from President Donald Trump about the Federal Reserve. Occasionally, one will merit a meme. But for the most part, the president’s tweets are dismissed either as evidence of frustration that he can’t simply fire Jerome Powell, his choice for Fed chair, or the search for a scapegoat if the U.S. economy falters and damages his re-election prospects.

Then came this missive on Wednesday:

The timing is obvious. It’s the day before the European Central Bank will presumably drop interest rates further below zero, and a week before the Fed’s own rate decision. A Washington Post-ABC News poll this week showed a majority of Americans fear the U.S. will enter a recession within a year. Stephen Moore, who withdrew his candidacy for the Fed board earlier this year, wrote a recent op-ed in the Wall Street Journal with the headline “Refinance U.S. Debt While Rates Are Low.”

Put it all together, and you have Trump’s two-part tweet. Unfortunately, the self-proclaimed “king of debt” doesn’t appear to truly understand it. Let’s unpack the president’s comments piece by piece:

The Federal Reserve should get our interest rates down to ZERO, or less

First, the Fed is already cutting its benchmark rate and is widely expected to drop it another 25 basis points on Sept. 18. A more significant reduction — and certainly to the extent the president wants — would probably just panic the markets. It could also severely damage banks, particularly if longer-term yields also tumble. Citigroup Inc., JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Wells Fargo & Co. this week already reduced their annual net interest income targets.

Second, the idea that Americans would willingly accept negative interest rates is very much an open question. After all, it’s not something they have ever had to deal with before. As Katherine Greifeld wrote for Bloomberg Businessweek, U.S.-based investors don’t just have the good fortune of buying Treasuries at above-zero interest rates. They can also easily turn the world’s $15 trillion pool of negative-yielding debt positive.

and we should then start to refinance our debt.

This is not something that the U.S. does in any significant way. The federal government is not like a company that issues bonds that can be bought back if borrowing costs fall. There’s no mechanism, for example, for the Treasury to get big investors to give back bonds issued in 1995 that mature in 2025 and pay 7.625% interest. In fact, these are likely among funds’ most-prized possessions because they boost both the credit quality and average payout of the overall portfolio.

INTEREST COST COULD BE BROUGHT WAY DOWN, while at the same time substantially lengthening the term.

This is hardly a given. The Fed controls only short-term interest rates, not long-term yields. In 2010, when the fed funds rate was near zero, the 10-year Treasury yield was 4%. If central bankers slash interest rates when the economy is on solid footing, it could boost inflation, which would cause yields on longer-term obligations to climb. The reason long-term rates in Japan and Germany are at or below zero is because their economies are stagnant and inflation is largely nonexistent.

As for “substantially lengthening the term,” the Treasury Department itself has found that there’s insufficient demand for ultra-long Treasuries that mature in 50 or 100 years. Yes, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin is taking another look, but the bond-market group that advises him is likely to dismiss the idea again.

Also, issuing ultra-long bonds would probably steepen the yield curve, again making the claim that “interest costs could be brought way down” dubious at best.

We have the great currency, power, and balance sheet

And yet, the president clearly wants a significantly weaker dollar, which, if done recklessly, could threaten its position as the reserve currency of the world.

The USA should always be paying the the lowest rate.

It goes without saying to anyone who took Macroeconomics 101 that stronger economies pay higher interest rates.

But setting that aside, why should the U.S. receive more favorable treatment than Germany? It has the same triple-A ratings from Moody’s Investors Service and Fitch Ratings, and Germany even has a top grade from S&P Global Ratings while the U.S. was dropped to AA+ in 2011.

Plus, investors are begging Germany to borrow more, rather than stick to its rigid balanced budget. That’s of no concern whatsoever for the U.S. — its budget deficit grew to $866.8 billion in the first 10 months of the fiscal year, up 27% from the period a year earlier. The gap is now projected to reach $1 trillion by the 2020 fiscal year, two years earlier than previously estimated. Supply and demand isn’t everything in the Treasury market, but it is something.

Obviously, the ECB has distorted the bond markets in its region. In Italy, which is barely rated investment-grade, 10-year debt yields less than 1%. But again, this is more a symptom of the lack of economic growth in the euro zone.

No Inflation!

Low inflation? Sure. But “no” inflation?

On Wednesday, a Labor Department report showed underlying U.S. producer prices increased 2.3% in August from a year earlier, topping the median forecast in a Bloomberg survey. Producer prices excluding food, energy and trade services rose 0.4% from the prior month, the most since April.

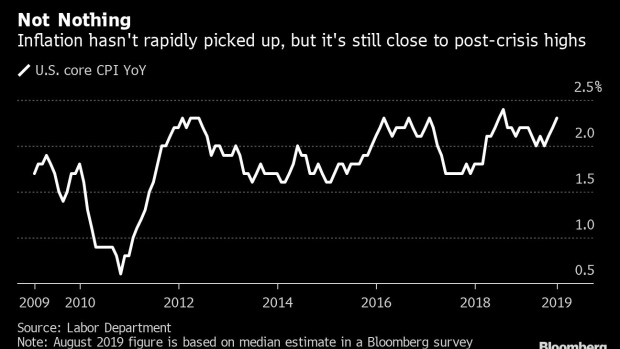

Those readings suggest Thursday’s consumer price index data could also meet or exceed expectations. Core CPI is already projected to rise to 2.3% year-over-year in August, which would be close to the fastest growth in the past decade. It’s fairly modest relative to the historical average, but it’s not nothing.

It is only the naïveté of Jay Powell and the Federal Reserve that doesn’t allow us to do what other countries are already doing.

Is this the first tweet from President Trump with accent marks?

It’s not naivete that is keeping the Fed from more drastic interest-rate cuts, but rather prudence and a focus on economic data. Fed officials saw some slight weakness earlier this year — business confidence was particularly rattled by the U.S.-China trade war — and provided a bit of accommodation to help ease concerns. Dropping interest rates to zero would serve little purpose except to most likely create a larger bubble in risky financial assets.

The president seems to think that Europe and Japan want negative interest rates. I’m fairly confident that the ECB and Bank of Japan wish they were in a similar position as the Fed, which was finally able to move away from the zero-bound and now has some breathing room in the event of an economic downturn.

A once in a lifetime opportunity that we are missing because of “Boneheads.”

Readers can draw their own conclusions about who’s truly boneheaded.

To contact the author of this story: Brian Chappatta at bchappatta1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.