Oct 27, 2021

U.K. Budget Signals Sunak Embracing Inflation to Erode Debt Pile

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- U.K. Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak appears to have embraced surging inflation.

With a budget that increased wages, cut taxes for low income households and pumped investment into public services, Sunak on Wednesday laid out plans to add 75 billion pounds ($103 billion) of stimulus across the next six years.

The spending spree will overheat the economy, with growth running above capacity for the next three years. That will drive up inflation but dramatically shrink borrowing, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility.

The move surprised economists anticipating greater fiscal restraint and left some with the impression that Sunak, while talking tough about the need to prevent an upward spiral in prices, is fanning those pressures as a way to escape the record 2.2 trillion-pound debt burden Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government built up during the pandemic.

“The government needs to be careful not to be seen to outright embrace inflation as a quick fix,” Mats Persson, a former Treasury adviser and now a partner at EY, said. Demands that companies raise pay suggest some parts of government are also compatible with rising prices, he added.

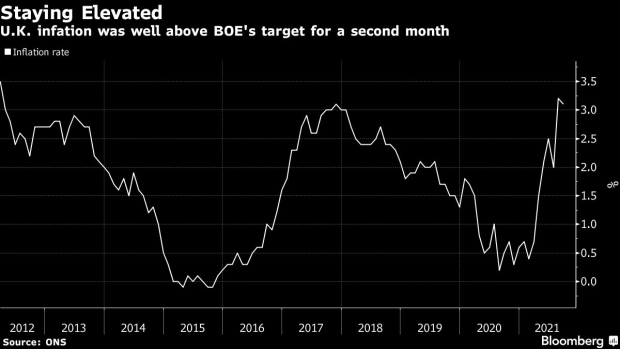

The OBR expects inflation to peak at “close to 5%”, more than double the Bank of England’s target. Sunak’s budget makes it a “little more likely” that the BOE would raise interest rates this year, according to Dan Hanson, senior economist at Bloomberg Economics. The central bank’s next decision is on Nov. 4.

The anticipated surge in prices will drive up the nominal size of the economy, which determines tax receipts. In cash terms, the economy is now forecast to be 4.1% larger in 2025/26 than projected in March. That’s equivalent to 110 billion pounds, the bulk of which was due to inflation.

As a direct result, the OBR cut its borrowing forecast by 154 billion pounds over the lifetime of the parliament. That was despite the chancellor’s 75 billion-pound spending spree and a 51 billion-pound increase in debt servicing costs.

“If what you were trying to do was to unwind high debt ratios, then this is exactly how you would go about it,” said Erik Britton, the managing director at Fathom Consulting who formerly served as a BOE official. “If you wanted a burst of inflation, you would announce a big increase in the minimum wage and public sector pay. That would then start to embed higher expectations in the private sector wage round.”

For his part, Sunak insisted that the government’s aim is to keep a lid on inflation before it squeezes the finances of consumers. “I understand people are concerned about inflation -- but they have a government here ready and willing to act,” he told Parliament on Wednesday.

The budget measures included:

- A 6.6% increase in the national minimum wage, which is more than double the current inflation rate

- Looser restrictions on pay for public-sector workers

- Tax cuts for the hospitality industry including restaurants and bars that were hard hit by lockdowns

- Lower excise duties for beer and wine

- A freeze in petrol duties and some taxes for heavy goods vehicles

- A tax break worth 13.6 billion pounds over six years for people receiving universal credit benefit payments

- An extra 65 billion of departmental spending over the parliament.

Those decisions, the Institute for Fiscal Studies said, made Sunak’s budget look more like the work of Gordon Brown, who served as chancellor in the Labour government from 1997 to 2007, than of George Osborne, a Conservative from the last decade.

The combination of higher growth and inflation increased tax receipts by around 50 billion pounds a year while lifting debt interest and welfare costs by 15 billion pounds, the OBR said. That gave Sunak a 38 billion-pound average annual windfall -- roughly half of which he spent.

Calls by ministers for businesses to increase pay chime with OBR scenarios published on Wednesday that show inflation driven by rising wages “lowers borrowing significantly over the medium term.”

Higher wage growth is likely to increase income tax and national insurance receipts by 27.6 billion pounds and VAT receipts by 8 billion in 2025/26 compared with the March forecast, the OBR said.

In July, the fiscal watchdog published analysis showing that a temporary inflation shock would eradicate a quarter of the debt increase relative to gross domestic product within three years. Even after the budget spending spree, the OBR estimated that the underlying debt ratio will stabilize at around 85% of GDP.

Embracing inflation carries some risks. If consumer prices increase but wages remain flat, borrowing rises in the short term as interest rates climb. That pushes up debt servicing costs, a second OBR inflation scenario published with the budget warned.

The budget forecasts were based on an increase in interest rates from 0.1% to 0.5% next year and to 0.75% in 2023, which is a slower path than markets currently expect. The OBR said earlier rate rises would be negative for the public finances.

John Glen, the Treasury’s economic secretary, rejected the idea that the budget would boost inflation.

“It’s a budget that says we have to have sustained growth,” he said in an interview on Bloomberg Television with Francine Lacqua. “It means spreading economic activity across the country. We’ve seen growth better than anticipated this year, and that gives us the flexibility to make some of these choices.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.