Jan 28, 2020

U.K. gives Huawei partial role in 5G network, breaking with U.S

, Bloomberg News

U.K. grants Huawei partial access to 5G network

Britain will let Huawei Technologies Co. play a limited role in building the country’s next-generation mobile phone networks, denying a long-running attempt by the U.S. to have the Chinese tech giant barred.

In a statement released midday in London, the U.K. said it will keep high risk vendors, alluding to Huawei, out of the most sensitive core parts of the networks but will allow the company to supply other gear that’s critical to the roll-out of 5G, such as antennas and base stations.

The country will also impose a cap of up to 35 per cent on the Shenzhen-based vendor’s radio access components, so phone carriers like BT Group Plc’s EE and Vodafone Group Plc may face a challenge reducing their dependence on Huawei. The Chinese company currently has a similar overall share of the U.K.’s 4G networks.

High risk vendors, a category which could also include China’s ZTE, which is already banned from the U.K., are also to be “excluded from sensitive geographic locations, such as nuclear sites and military bases.”

The recommended 35 per cent cap will be kept under review and could reduce over time, the statement said. BT is already set to switch out Huawei core network components inherited when it bought the EE mobile network in 2016.

The widely-expected announcement by Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government is a compromise between the outright ban on Huawei sought by the U.S. and the access sought by telecommunication companies. While it ends months of political wrangling, the process remains fraught with peril for Johnson as he prepares to end 47 years of European Union membership for the U.K.

In a statement, Huawei Vice-President Victor Zhang said it was “reassured” that the U.K. will let the company keep working with carriers on 5G.

“This evidence-based decision will result in a more advanced, more secure and more cost-effective telecoms infrastructure that is fit for the future,” he said, committing to build on Huawei’s more than 15 years supplying U.K. telecom operators.

The Confederation of British Industry, the leading business lobby in the country, said “this solution appears a sensible compromise that gives the UK access to cutting-edge technology, whilst building in appropriate checks and balances around security.” Vodafone Group Plc, which uses Huawei in its U.K. radio network, said “we aim to keep any potential disruption to customers to a minimum.”

A key pillar of Johnson’s vision for a future outside the world’s richest single market is a trade deal with the U.S. and the Huawei license risks setting up a clash with President Donald Trump.

By curbing Huawei’s access but still allowing the supplier to play a role in 5G, British officials are betting they can manage any security risks at home and still maintain intelligence-sharing ties with the U.S. and other allies.

Johnson discussed Huawei in a phone call with Trump on Friday, and clearly wasn’t swayed by the push for a total ban. The prime minister said the U.K. could have the best of both worlds: retaining access to the best technology while protecting the data of consumers. British security services deem the risks manageable.

For the U.K. timing of its announcement is particularly sensitive. U.S. Secretary of State Michael Pompeo, who had warned Johnson’s predecessor not to “wobble” on the issue, is due to visit on Wednesday.

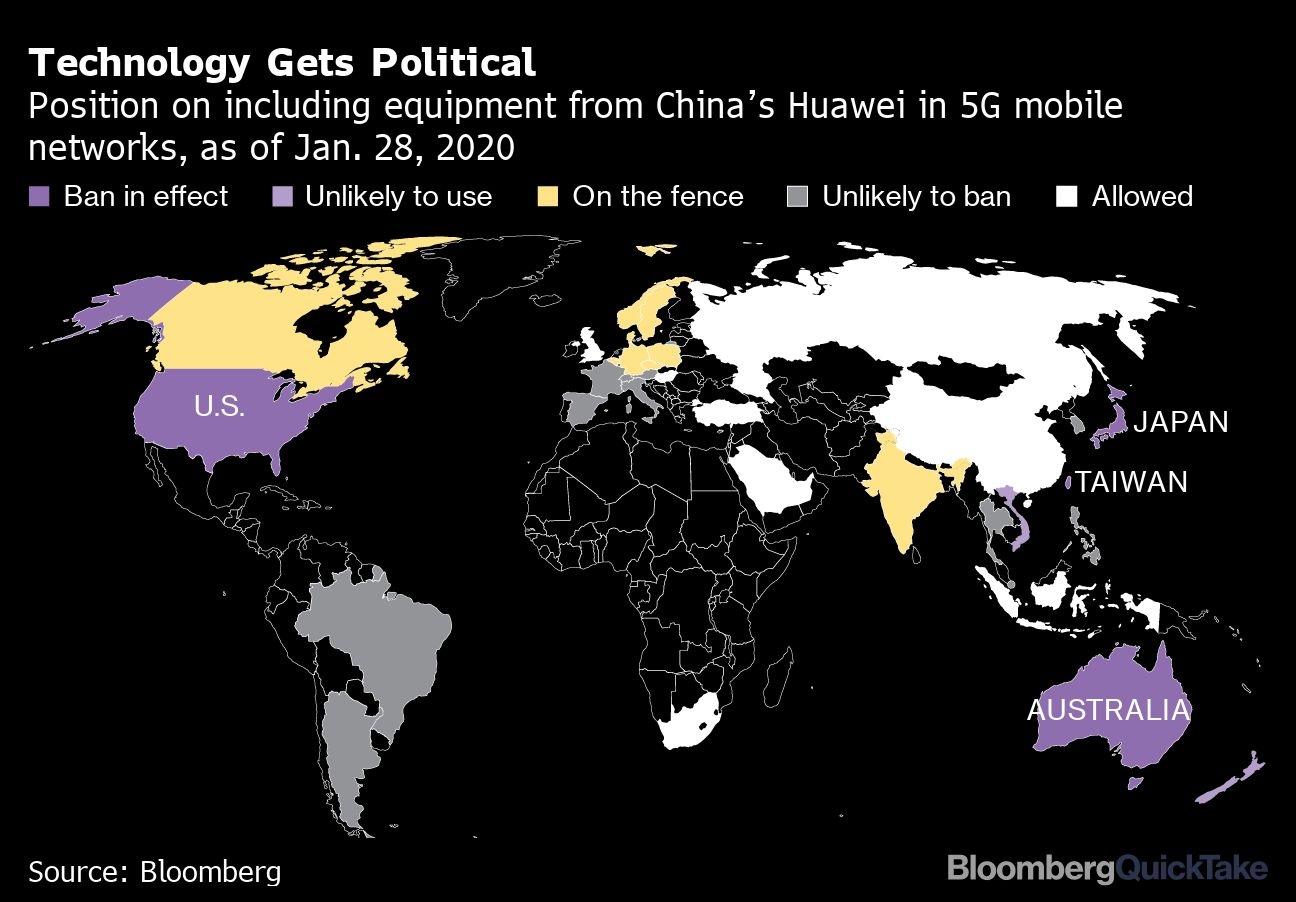

Huawei has been a key supplier to the U.K. and many other European phone networks for over a decade so this decision will be closely watched by others. In fact, many European nations and Canada are leaning in the same direction as the U.K.

The EU will publish its own guidelines on Wednesday which give leeway to member states to restrict or ban Huawei without forcing them to do so. According to a draft of the document seen by Bloomberg, countries should consider banning suppliers based in countries with insufficient “democratic checks and balances” from core 5G components.

A key concern of the U.S. is that other countries will copy-and-paste the U.K.’s solution, relying on its regulatory system and high level of access to Huawei technology.

“The U.K. model isn’t easily replicated,” warned Ian Levy, technical director of the National Cyber Security Centre, in a blog published alongside the decision. “The approach we’ve come up with for the U.K. is specific to the U.K. context. Others shouldn’t assume they’re getting the same level of protection for modern networks if they do similar things without performing their own analysis.”

The market is broken, he added, because it’s not commercially attractive to build good security into networks.

--With assistance from Olivia Konotey-Ahulu.