Sep 12, 2019

U.S. and China Are Growing Hungry for a Trade Deal

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- There’s nothing like an empty stomach to focus your mind. That may be driving the trade talks between the U.S. and China as close to a truce as they’ve been in months.

China is considering renewed imports of U.S. products such as soybeans and pig meat which have been under unofficial embargo as a result of the trade war, Bloomberg News reported Thursday. That would be a gesture of goodwill ahead of the next round of bilateral talks and may take the edge off pork prices, which rose 47% from a year earlier last month.

President Donald Trump is in a similarly forgiving mood, promising Wednesday night to delay a slice of tariffs worth about $12.5 billion:

Could we be on the verge of a breakthrough?

There are certainly signs that the pressure of recent months is starting to weigh on both sides. China suffers a perpetual three-year boom-bust cycle in pork prices, as we’ve written, but this year the effects of culling animals to stop the spread of African Swine Fever have caused the biggest price spike since 2011.

Solving the protein shortfall has clearly been preoccupying the country’s leadership. U.S. pork imports are restricted because of China’s ban on a feed additive common in America. Imports of U.S. soybeans, a crucial high-protein ingredient in animal feed, have also been limited by government diktat, as well as by the destruction of much of the U.S. crop in floods earlier this year.

Beijing’s concern extends all the way to Brazil, which recently overtook the U.S. as the biggest soybean producer and is a major meat exporter as well. President Jair Bolsonaro is expected to visit China in October and President Xi Jinping will return the gesture the following month, Bolsonaro’s vice president said Monday. China also authorized an additional 25 meat-packing plants for exports, bringing the total to 89, Reuters reported.

That’s a remarkable love affair by the standards of Beijing’s prickly diplomacy, as Bolsonaro has gone out of his way to antagonize China since starting his campaign for the Brazilian presidency.

More changes are afoot just across Brazil’s southern border. Argentine soy crushers will finally be able to export soy meal to China after 20 years of talks, Bloomberg News reported this week. That could mean China-bound shipments for the world’s biggest exporter of animal feed from early next year.

The way China is moving on agricultural trade with South America suggests Beijing has a long-term plan to reorient its agricultural import dependence toward smaller countries that it has a better chance of dominating diplomatically. At the same time, there’s clearly also a short-term problem around food supplies generally, and taking the foot off the brake on U.S. imports can only help.

The hunger in the U.S. is more metaphorical, but no less real. The farm belt’s loyal Trump voters are hurting. Net farm income will increase this year by about 4.8%, the U.S. Department of Agriculture forecast last month, but the figure would be in decline were it not for a $5.8 billion increase in direct government payments, which will amount to about 22% of the $88 billion total income.

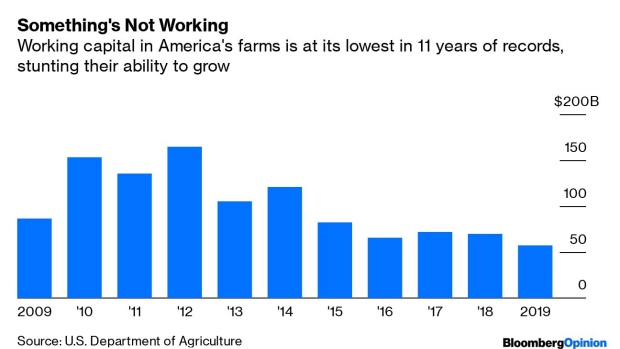

Low interest rates over the past decade have ensured that bankruptcy rates for U.S. farms have remained relatively subdued, but less catastrophic measures of financial stress suggest money is getting tight. Working capital in the sector, which was as high as $165 billion in 2012, is forecast by the USDA to fall to $57 billion this year, its worst level in 11 years of records. As a share of gross revenues, that’s just 13%, also a record low.

The risk is that a deepening trade conflict could push things to the point where government subsidies aren’t enough to support the sector. A gradual retreat of Chinese demand could hollow out the U.S. farm belt, the way the trade boom of the 2000s decimated their near-neighbors in the rust belt. Much of America’s industrial heartland is already suffering recessionary conditions as the trade war drags on.

A revival of the farm-focused deal that the two sides were working on before talks broke down in May would at least slow China’s pivot away from dependence on U.S. agricultural exports, and keep up food supplies to that country’s 1.39 billion people. What this dispute’s been lacking hunger for a deal. Now we may finally be seeing it.

To contact the author of this story: David Fickling at dfickling@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.