Mar 12, 2022

U.S. Economy Can Likely Weather Russia Crisis Shock But Democrats Face Peril

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Inflation-walloped Americans are largely prepared to withstand the economic pain imposed by Russia’s Ukraine invasion. That may be little solace for President Joe Biden’s Democrats, who will pay a price at the ballot box for the surging cost of living, if history is any guide.

Consumer prices were already rising at the fastest pace in four decades even before the hit to energy and food supply chains caused by the war and sanctions imposed by the U.S. and its allies on Russia. Gasoline prices are already up about 20% this month, reaching an unprecedented $4.33 a gallon in recent days — contributing to the weakest consumer sentiment in more than a decade.

Americans have overwhelmingly supported banning Russian oil imports, a step Biden took Tuesday. At the same time, polls show a majority see the nation as on the wrong track, and fault Biden’s handling of the economy, particularly on inflation. Biden now might be running out of time to turn opinions around before Democrats have to defend their razor-thin congressional majorities in November's elections.

Voters tend to lock in their perceptions of the economy six to nine months before an election, said Christopher Wlezien, a political economist at the University of Texas at Austin who’s been analyzing elections for more than three decades.

“Things that happen late can still matter, but over time you have more and more history to overcome,” Wlezien says of election campaigns.

Economists have scrambled to incorporate the impact of the geopolitical crisis. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. sees about a 20% to 35% chance of a recession in the next year. But put another way, their baseline is in accord with the assessment of Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, who said Thursday she didn’t expect an economic downturn.

“We haven’t derailed our view on a still-solid recovery,” Bruce Kasman, chief economist at JPMorgan Chase & Co., said on Bloomberg Television Friday. “The U.S. economy has shown already pretty significant resilience in the face of shocks — the underpinnings are healthy.”

The latest shock comes against a backdrop of a powerful economic recovery.

The unemployment rate is historically low at 3.8%, and there’s a notable cushion of savings thanks to unprecedented federal support for households the past two years — median checking-account balances at the end of last year were well above 2019 levels, especially for lower-income Americans, analysis by the JPMorgan Chase Institute shows. And total consumer spending, adjusted for inflation, is notably higher now than before the pandemic. Furthermore, gasoline makes up less than 4% of the average consumer basket.

The Biden administration has blamed inflation on Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of his neighbor. This is “Putin’s price hike,” the president said Tuesday with regard to gas-price increases.

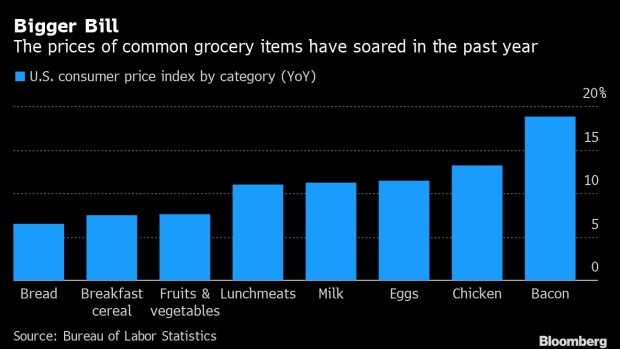

Trouble is, price gains are a whole lot broader than just energy, and they began well before the war. Americans are also simultaneously dealing with higher rent and food costs, along with the biggest jump in the cost of services — a category including airfares and hotel stays — since 1991. And inflation may not peak until April, according to Bloomberg Economics. Depending on how high oil prices rise, consumer-price increases could reach 9% or even over 10%.

“I’m worrying about what will happen tomorrow,” says Naomi Ogutu, a 45-year-old single mother of three who’s been driving for Uber and Lyft since 2016 in New York and New Jersey after immigrating from Kenya in 2012. She used to spend about $200 per week on gas for her rideshare work but now pays $300.

Most economists expect there to be at least some impact on consumer spending this year from the war overseas. As people spend more on necessities, they have less money to spend on discretionary items and services like dining out.

If oil prices stay near $120 a barrel for the rest of the year, then gasoline prices would likely average $4.40 a gallon, for an increase of $1.40, according to Oxford Economics. That would represent an additional cost of $190 billion this year for U.S. families -- or $1,500 per household, says Lydia Boussour, the research group’s lead U.S. economist.

Six months ago, Chris Cary was doling out $500 a week in payday advances to workers at the two Virginia franchises of his staffing agency, Express Employment Professionals, in Newport News and Chesapeake — loaning the money interest-free and deducting it from their checks. That’s ballooned to $1,000 to $2,000 a week recently, with most workers citing transportation costs.

“We're getting two or three a day saying, ‘I need gas money,’” Cary says of his employees.

Political Risk

Democrats were already facing a difficult issue environment heading into the November elections, having lost ground in Virginia and other states in the off-cycle election last year. The sitting president’s party typically suffers a reversal in support during the midterms.

Biden’s approval rating — which really started to suffer in the chaos following the U.S.’s withdrawal from Afghanistan — now stands at 42.9%, roughly 10 points below this time last year, according to the RealClearPolitics average. An Economist/YouGov poll earlier this month found that 61% of Americans thought that inflation was a “very serious” problem. That number was even higher among registered voters, independents and suburbanites — the people Democrats most need to keep their razor-thin control of the House and Senate.

The president at least may win support for his strong stance against Putin.

“I support the higher good of protecting U.S. allies” even with higher prices, says Carol Reyes, a resident of the Atlanta suburb of Lawrenceville. “I haven’t thought of the breaking point, but nothing could sway my vote for freedom,” says the 50-year-old Democrat, who’s been making ends meet with credit cards since the pandemic.

While the prospects for the conflict in Ukraine are uncertain, Ethan Harris, head of global economics at Bank of America Corp., emphasizes the crisis is “a significant shock hitting a fundamentally strong backdrop.”

“We will get a lot more worried if we see two kinds of developments,” Harris says. First is a cut-off of Russian energy so severe it sends crude oil spiking to $175 a barrel, averaging $130 for the year. Second is a failure of inflation to recede, spurring the Federal Reserve to tackle inflation more aggressively. “Combining a major oil shock with serious policy tightening implies a serious risk of recession.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.