Jul 25, 2019

U.S. immigration policy hands Canada an opening in tech

, Bloomberg News

Croxon: Tech giants foster competition within the startup space

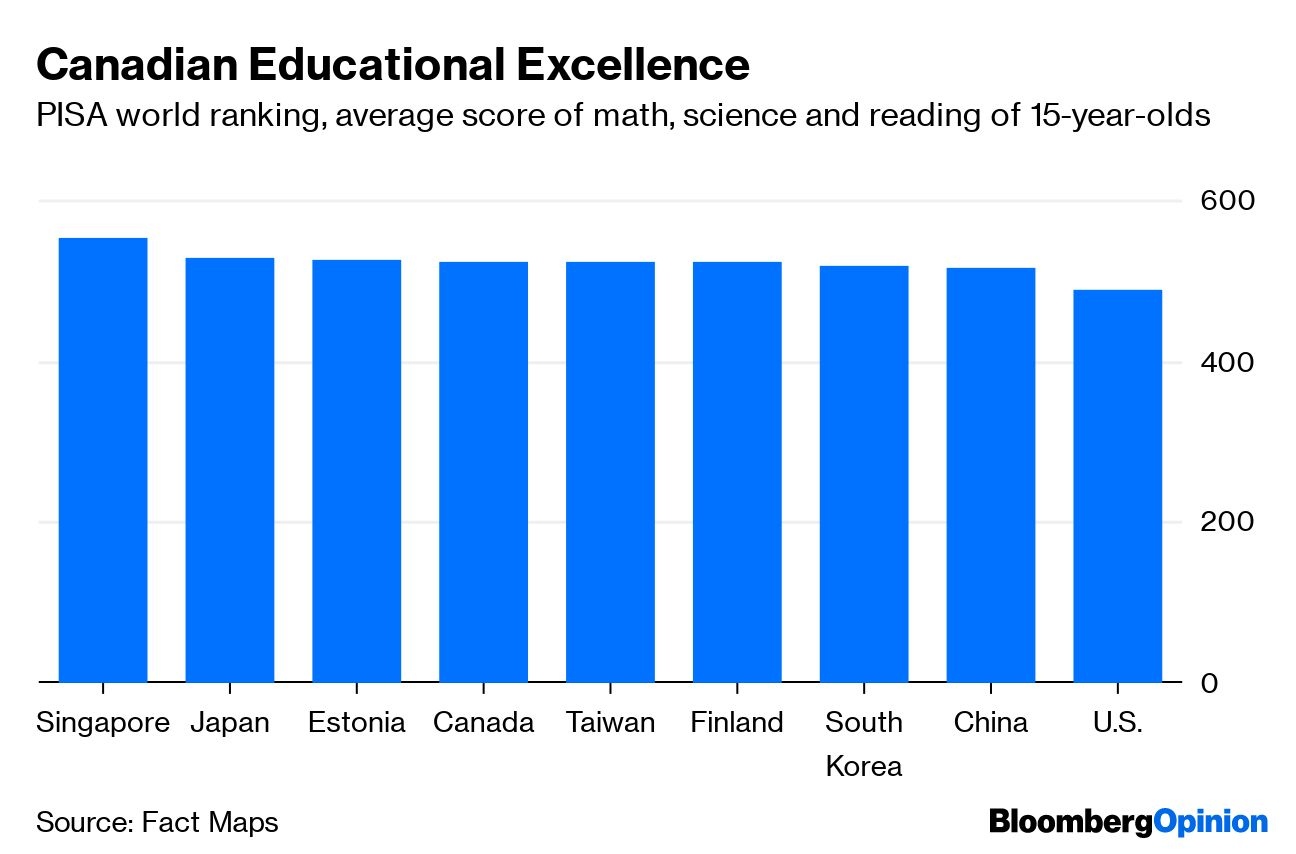

Canada ought to have a world-beating technology industry. The country has arguably the best system for admitting high-skilled immigrants. As a rich country, Canada has plenty of capital to direct toward building tech companies. The legal environment for venture capital and startups is very similar to that of the U.S., and taxes are not much higher. With its proximity to the U.S., its English proficiency, and its cultural ties to both Europe and Asia, it should have little problem selling into the biggest markets. And its educational system is one of the world’s highest-ranked:

Canadian cities such as Toronto and Vancouver would make great tech hubs. They’re beautiful, safe and fun -- just the kind of place that young educated workers should enjoy living in. And even after recent rent increases, they’re more affordable than San Francisco, Los Angeles or New York.

Yet despite these advantages, Canada’s technology industry has remained modest. Although it has risen in Bloomberg’s Innovation Index recently, the country is still 12 spots behind the U.S., which sits at eighth place. Research in Motion, Canada’s former flagship tech company and manufacturer of the BlackBerry, famously lost the smartphone race despite a strong early lead. And no others have grown up to replace it, meaning most Canadian engineers have to seek employment at small startups or at offices of foreign tech companies if they want to stay in Canada. As of May 2018, Silicon Valley boasted 57 tech unicorns (private companies worth more than US$1 billion); Toronto and Vancouver each had zero.

What has held back Canada’s tech industry? In a word, geography. Canada’s proximity to the U.S., as well as their shared language and the U.S.’s relatively relaxed policy toward Canadian immigration, is both a blessing and a curse. Canada’s best and brightest young workers have long had the option of going to work to Silicon Valley. If you’re an engineer in Vancouver, why not hop across the border to work in Seattle, home of Amazon, Microsoft and Boeing? If you’re living in Toronto, the bright lights of New York beckon. A number of prominent tech founders, like Stewart Butterfield of Slack Technologies and Garrett Camp of Uber Technologies, started their companies south of the border.

This reflects what economists call the clustering effect. Venture capitalists, start-up founders, big companies, and engineers all want to be near each other, in order to have the maximum number of options, and also to take advantage of the ideas and expertise that seem to permeate the air in places like Silicon Valley. Because the U.S. tech hubs have a big head start, Canada’s cities are left struggling to get off the ground.

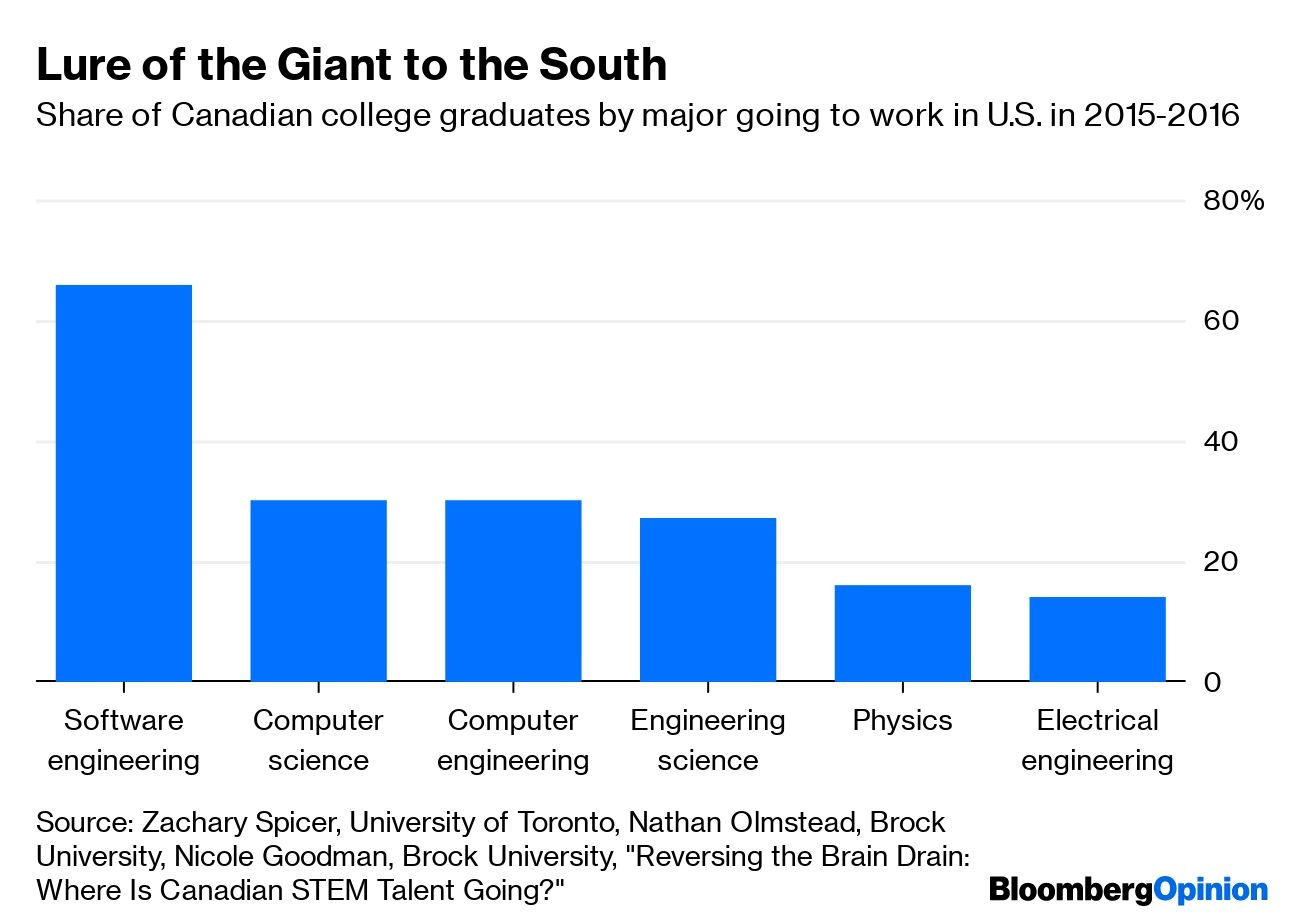

A report by researchers at the University of Toronto and Brock University found that large percentages of Canadian science and engineering graduates from top universities in the classes of 2015 and 2016 went to work in the U.S. For software engineers, the rate of brain drain was enormous:

As fast as Canada can train smart young engineers, they leave for greener pastures.

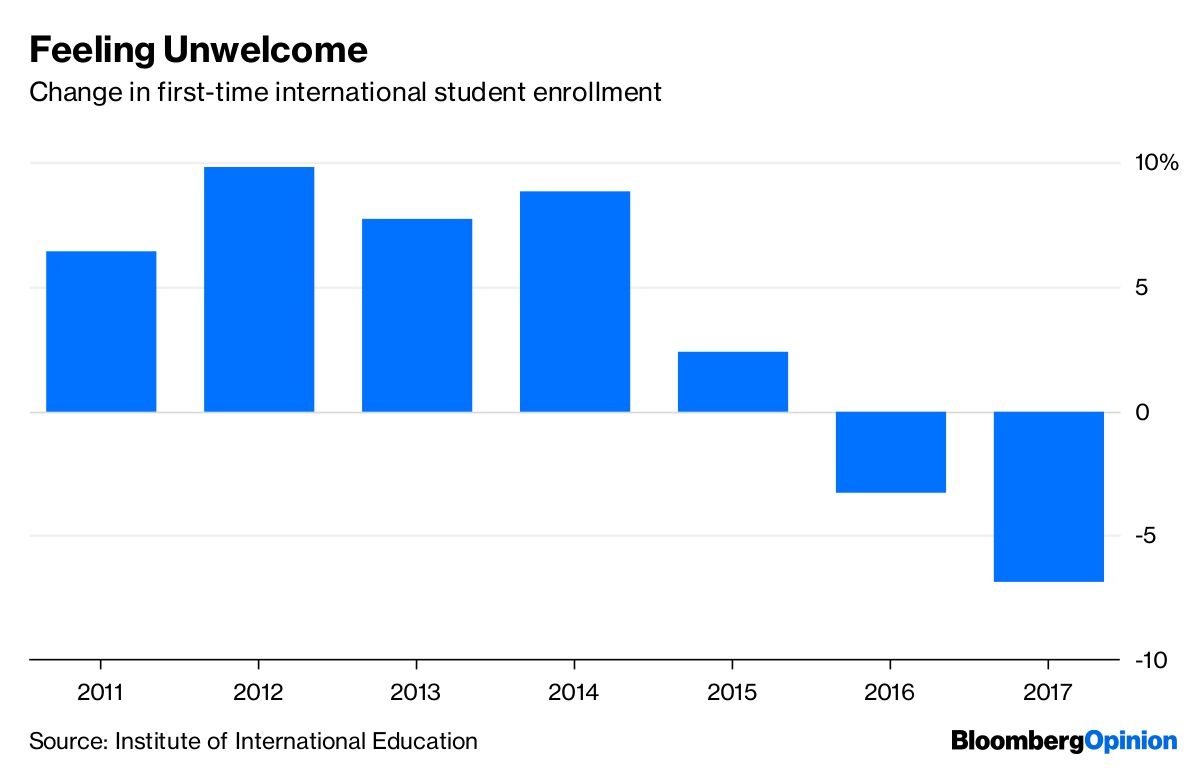

But the winds may be changing. Silicon Valley, New York and Seattle have one major weakness -- they are located in a country that has chosen to elect Donald Trump as president. Trump’s restrictive policies toward high-skilled immigration, combined with his general xenophobic attitude and rhetoric, are making the U.S. look like a less attractive destination for foreign talent. This is visible in the shrinking enrollment of foreign students in the U.S.:

Trump’s stands on immigration could make some Canadians wary of working in the U.S., and slow the brain drain. Even more importantly, it could divert more skilled immigrants to cities like Toronto and Vancouver -- what Canada loses in native-born outmigration, it might be able to make up in overseas recruits. Since the beginning of 2018, job-search website Indeed has found rising foreign interest in Canadian so-called STEM jobs. A new Canadian program to recruit high-skilled immigrants has pulled in about 24,000 during the past two years. Meanwhile, venture investment in Canada has grown, totaling US$2.9 billion in 2018 -- a modest sum, but in per capita terms almost equal to the U.S.

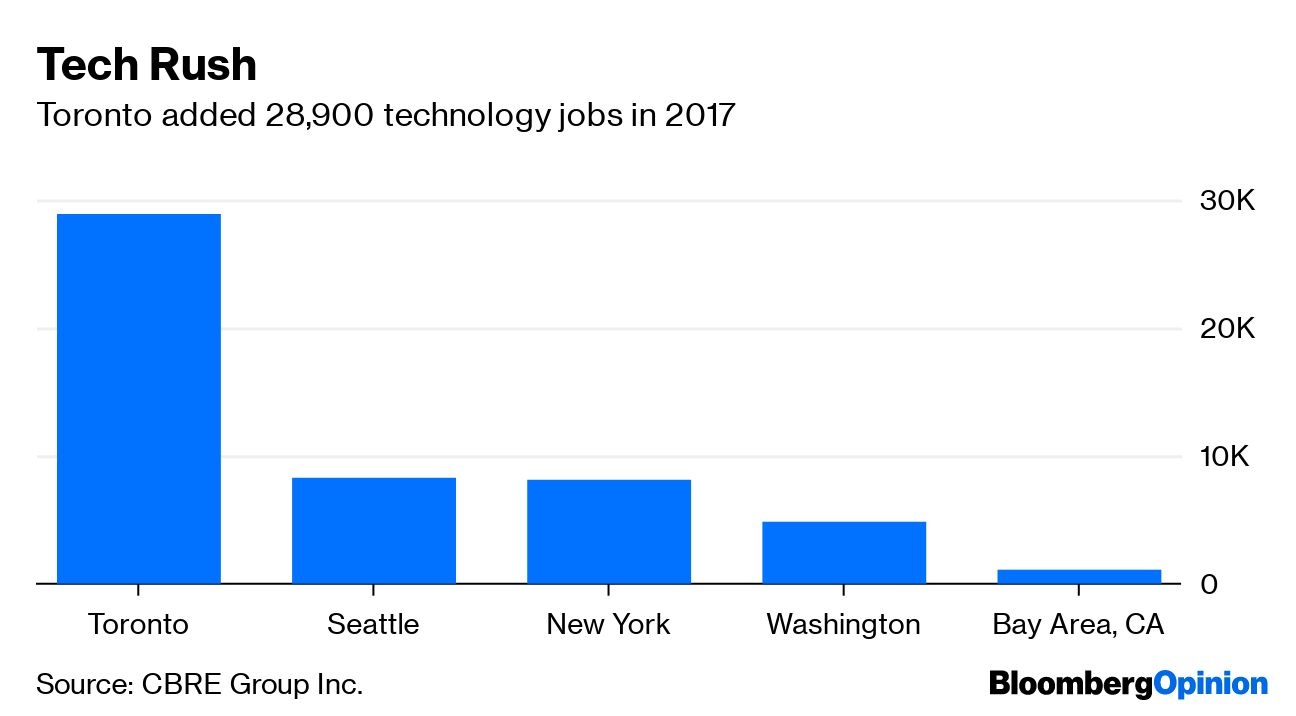

Toronto, in particular, may be well poised to capitalize. In 2017, it added more tech jobs than the San Francisco Bay Area, Seattle or New York:

Toronto’s government, business community and universities have come together to promote a unified development strategy, including government funds and university-business partnerships. U.S. tech giants are opening up offices in the city, and startups are multiplying. Vancouver, too, is trying to become a tech hub, with the province of British Columbia boasting a large number of startups. And Ottawa is a contender as well, with a large concentration of tech jobs.

There are additional steps the Canadian government could take to help its budding technology hubs. It could ban the enforcement of noncompete employment clauses, as California does, barring workers from taking jobs with corporate competitors. And it could spend a lot more on research, which at only 1.53 per cent of gross domestic product is much lower than the 2.74 per cent spent by the U.S.

Meanwhile, some U.S. tech clusters are threatened not only by Trump, but by their own self-inflicted wounds. Thanks to local political interests blocking new housing development, rents in the San Francisco Bay Area have grown unbearable for many young workers. San Francisco has epidemics of property crime and homelessness. Meanwhile, New York is quietly bleeding population, and has taken a more adversarial stance toward technology companies in recent years.

The U.S.’s fabled tech clusters may therefore have reached their apogee. The outflow of workers and capital from these cities will benefit other cities throughout the U.S., but nowhere in the country is safe from Trump’s immigration policies. A great opportunity for Canada awaits.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.