Jan 12, 2023

U.S. inflation cools again, putting Fed on track to downshift

, Bloomberg News

The Fed may have already gone too far: Investment strategist David Dietze

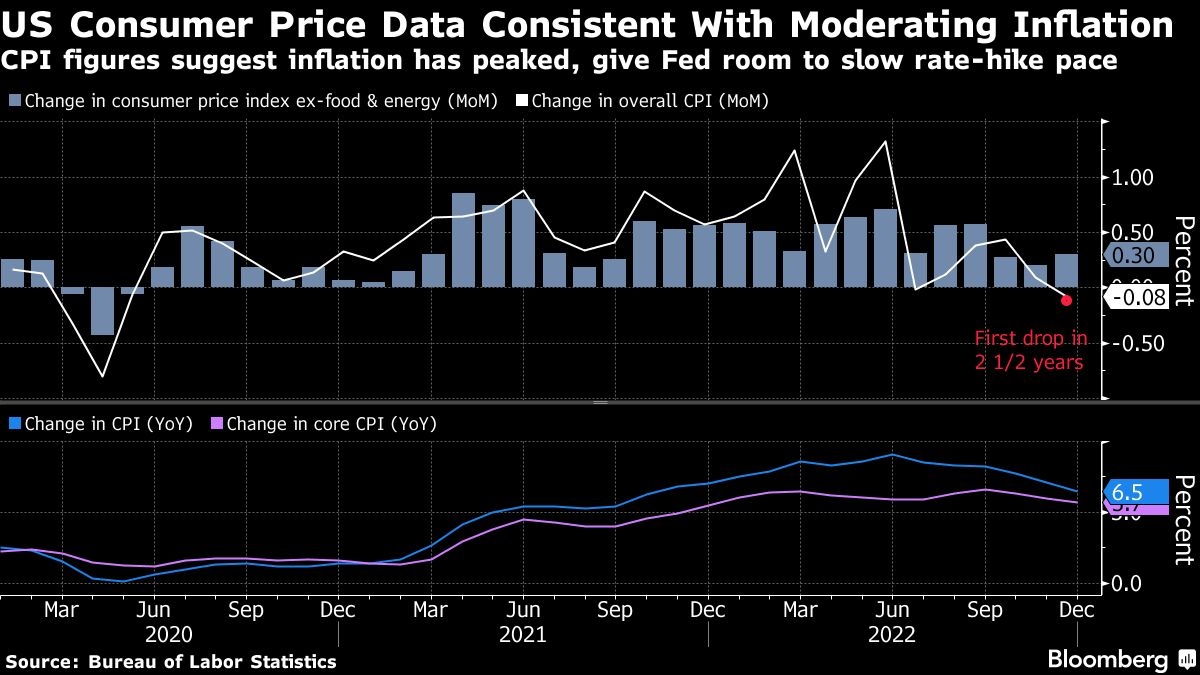

U.S. inflation continued to slow in December, adding to evidence price pressures have peaked and putting the Federal Reserve on track to again slow the pace of interest-rate hikes.

The overall consumer price index fell 0.1 per cent from the prior month, with cheaper energy costs fueling the first decline in 2 1/2 years, according to a Labor Department report Thursday. The measure was up 6.5 per cent from a year earlier, the lowest since October 2021.

Excluding food and energy, the so-called core CPI rose 0.3 per cent last month and was up 5.7 per cent from a year earlier, the slowest pace since December 2021. Economists see the gauge — known as the core CPI — as a better indicator of underlying inflation than the headline measure.

The data, when paired with prior months’ lower-than-expected readings, point to more consistent signs that inflation is easing and may pave the way for the Fed to downshift to a quarter-point hike at their next meeting ending Feb. 1. That said, the central bank’s work is far from over.

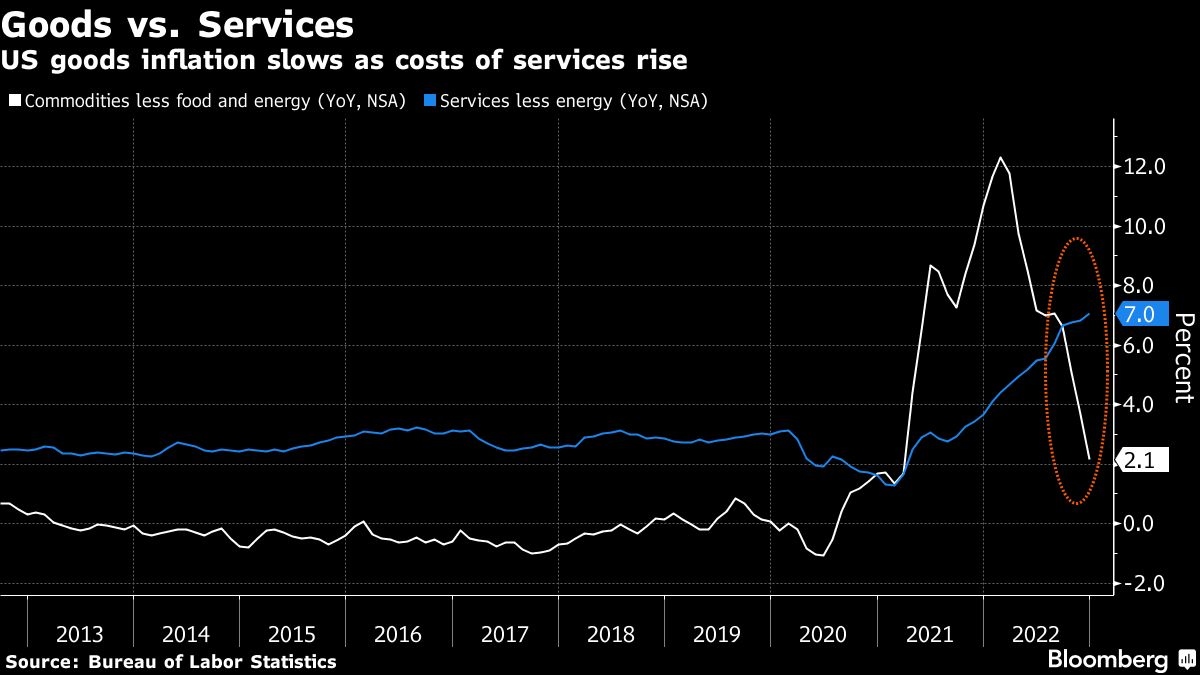

Resilient consumer demand, particularly for services, paired with a tight labor market threaten to keep upward pressure on prices.

The Fed is expected to raise interest rates further before pausing to assess how the most aggressive tightening cycle in decades is impacting the economy. Policymakers have emphasized the need to hold rates at an elevated level for quite some time and cautioned against underestimating their will to do so. Investors are still betting the central bank will cut rates by year end, despite officials saying otherwise.

Shortly after the report was released, Philadelphia Fed President Patrick Harker said the central bank should lift interest rates in quarter-point increments “going forward” as it approaches the end point in its hiking campaign.

The S&P 500 opened higher and Treasuries advanced while the dollar fell. All of the figures matched the median estimates in a Bloomberg survey of economists.

What Bloomberg Economics Says...

“A mostly favorable December CPI report gives the Fed room to further downshift the pace of rate hikes to 25 basis points at the Jan. 31-Feb. 1 meeting. We expect the Fed funds rate to peak at 5 per cent in March and stay at that level for the rest of the year.”

—Anna Wong, economist

Shelter costs — which are the biggest services component and make up about a third of the overall CPI index — increased 0.8 per cent last month, an acceleration from November. Rents and owners’ equivalent rent both rose by the same amount, while hotel stays advanced 1.5 per cent after falling in the prior month.

Because of the way this category is calculated, there’s a delay between real-time measures — which currently show rents are beginning to decline — and the Labor Department data.

Stripping out energy, rent and owners’ equivalent rent, services prices were up 0.3 per cent, according to Bloomberg calculations. Fed Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues have stressed the importance of looking at such a metric when assessing the nation’s inflation trajectory.

Removing medical care as well, an adjustment that helps offset a quirk in the CPI’s calculation of health insurance, services prices were up by a similar amount.

Given wages make up a large share of these businesses’ costs, economists expect the labor market to play a key role in the inflation outlook. The latest jobs report showed some cooling in earnings growth, but hiring remains robust and the unemployment rate fell to match a five-decade low.

The persistent imbalance between labor supply and demand remains firmly entrenched, underpinning wage growth and consumer spending at a time when the Fed is trying to slow it down. A separate report Thursday showed inflation-adjusted average hourly earnings rose 0.4 per cent from the prior month, the most in five months. Still, they were down 1.7 per cent from a year earlier.

Other data showed applications for unemployment benefits remained historically low last week.

Monthly Price Moves

- Food at home +0.2 per cent, smallest since March 2021

- Fuel oil -16.6 per cent, biggest decline since February 1990

- Household furnishings +0.2 per cent

- Used cars -2.5 per cent, sixth-straight decline

- Apparel +0.5 per cent, most since June

- Airfares -3.1 per cent, biggest drop since August

- Medical care services +0.1 per cent, first rise in three months

Excluding food and energy, goods prices fell 0.3 per cent, led by used cars. Gasoline prices dropped 9.4 per cent, “by far” the largest contributor to the decrease in the headline figure, the report said.

A rotation in spending from goods to services continues to weigh on merchandise prices. A further retreat in goods prices is expected to be a major driver of a rapid descent in annual core CPI in 2023, building on a pullback in the final months of last year.

While it’s broadly expected for annual price growth to substantially slow this year, a lot of uncertainty remains as to how far inflation may fall and whether the Fed’s rapid rate increases ultimately tip the U.S. into recession.

The inflation trajectory will be determined in several crucial areas. Some are domestic — the job and housing markets — and others are global, including supply chains and geopolitical tensions.

The Fed will also have December data on its preferred inflation gauge, the personal consumption expenditures price index, in hand before its decision next month. Central bankers anticipate that measure to moderate considerably this year, but won’t near its 2 per cent goal until 2025.

Another data point to consider will be the employment cost index for the fourth quarter, which comes out at the start of the Fed’s two-day meeting.