Aug 10, 2022

U.S. inflation runs cooler than forecast, easing pressure on Fed

, Bloomberg News

U.S. CPI data doesn't show inflation has peaked, but prices are cooling: JP Morgan's Manley

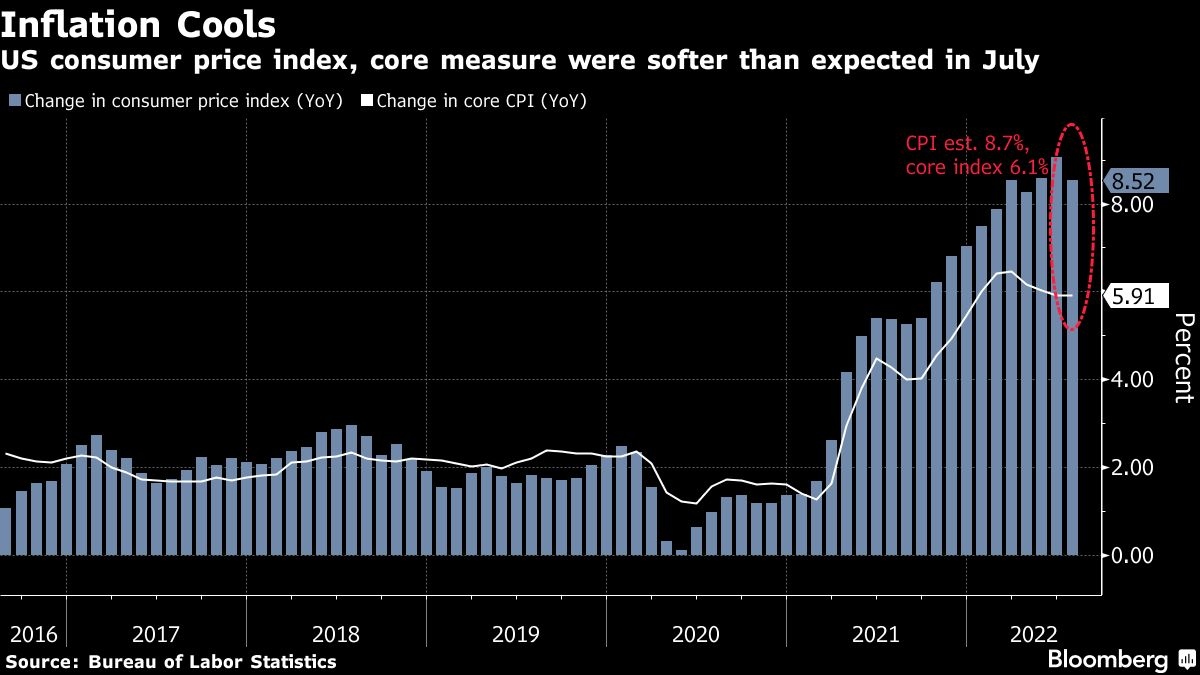

US inflation decelerated in July by more than expected, reflecting lower energy prices, which may take some pressure off the Federal Reserve to continue aggressively hiking interest rates.

The consumer price index increased 8.5 per cent from a year earlier, cooling from the 9.1 per cent June advance that was the largest in four decades, Labor Department data showed Wednesday. Prices were unchanged from the prior month. A decline in gasoline offset increases in food and shelter costs.

So-called core CPI, which strips out the more volatile food and energy components, rose 0.3 per cent from June and 5.9 per cent from a year ago. The core and overall measures came in below forecast.

The data may give the Fed some breathing room, and the cooling in gas prices, as well as used cars, offers respite to consumers. But annual inflation remains high at more than 8 per cent and food costs continue to rise, providing little relief for President Joe Biden and the Democrats ahead of midterm elections.

COST OF LIVING

While a drop in gasoline prices is good news for Americans, their cost of living is still painfully high, forcing many to load up on credit cards and drain savings. After data last week showed still-robust labor demand and firmer wage growth, a further deceleration in inflation could take some of the urgency off the Fed to extend outsize interest-rate hikes.

Treasury yields slid across the curve while the S&P 500 was higher and the dollar plunged. Traders now see a 50-basis-point rate increase next month as more likely, rather than 75.

“This is a necessary print for the Fed, but it’s not sufficient,” Michael Pond, head of inflation market strategy at Barclays Plc said on Bloomberg TV. “We need to see a lot more.”

Fed officials have said they want to see months of evidence that prices are cooling, especially in the core gauge. They’ll have another round of monthly CPI and jobs reports before their next policy meeting on Sept. 20-21.

Gasoline prices fell 7.7 per cent in July, the most since April 2020, after rising 11.2 per cent a month earlier. Utility prices fell 3.6 per cent from June, the most since May 2009.

Food costs, however, climbed 10.9 per cent from a year ago, the most since 1979. Used car prices decreased.

What Bloomberg Economics Says...

“With rents still pushing higher and elevated wages beginning to seep into services inflation, we expect this pause to be short-lived. Core CPI could approach 7 per cent in the coming months -- despite our assumption of moderation in goods prices.”

--Anna Wong and Andrew Husby, economists

Shelter costs -- which are the biggest services’ component and make up about a third of the overall CPI index -- rose 0.5 per cent from June and 5.7 per cent from last year, the most since 1991. That reflected a 0.7 per cent jump in rent of primary of residence. Hotels, meanwhile, fell 3.2 per cent.

Elsewhere in leisure, airfares dropped 7.8 per cent from the prior month, the most in nearly a year.

While prices are showing signs of moderating, there are several factors that risk keeping inflation high. Housing costs are a big one, as well as unexpected supply shocks. And wages are still climbing at a historically fast pace, concerning some economists of a so-called wage-price spiral.

However, those gains aren’t keeping up with inflation. A separate report showed real average hourly earnings fell 3 per cent in July from a year earlier, dropping every month since April 2021.

“We’re seeing a stronger labor market, where jobs are booming and Americans are working, and we’re seeing some signs that inflation may be beginning to moderate,” Biden said after the report. He cautioned, “we could face additional headwinds in the months ahead,” citing the war in Europe, supply-chain delays and pandemic-related disruptions in Asia.

The impact of inflation on wages has started to dent spending, with the pace of personal consumption growth decelerating between the first and second quarters.

That said, consumer expectations for US inflation declined sharply in the latest survey by the New York Fed, suggesting Americans have some confidence that prices will come off the boil in the next one to five years.