Jan 20, 2022

U.S. Labor’s Watershed Year Failed to Boost Union Memberships

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- After a year marked by weekslong labor strikes and unprecedented movements to organize at some of the largest corporations in the U.S., unionization levels fell back to historic lows.

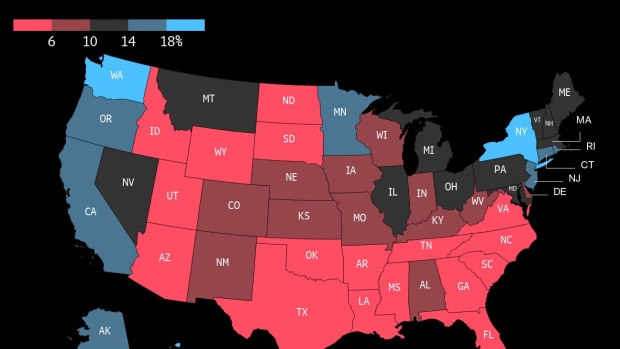

The rate of union membership, or the percentage of wage and salary workers who were part of a union, dropped to 10.3% in 2021, matching the record low in 2019, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data released Thursday.

Among private-sector workers, the numbers were even bleaker: union members made up just 6.1% of that workforce, compared to 33.9% of the public sector.

“There’s no denying that there has been an upsurge in worker activism over the last few years, and it’s obvious that large numbers of workers are fed up, and the conditions of the pandemic just aggravated it,” Wilma Liebman, who chaired the National Labor Relations Board under President Barack Obama, said before the latest data was released. “But it’s not translating into increased numbers for unions.”

Last year, U.S. workers seized attention through individual choices like quitting their jobs in record numbers and collective action including strikes by union members at Deere & Co., Kellogg Co., and Columbia University -- as well as non-union walkouts at companies like Activision Blizzard Inc. and McDonald’s Corp.

They also mounted high-profile unionization campaigns at top U.S. companies, including a failed union vote among thousands of Amazon.com Inc. workers in Alabama, and a successful ones among a few dozen Starbucks Corp. staff in New York.

But these actions didn’t translate into more overall members. That’s partly because successes like those at Starbucks remained limited in scope, and workers at big corporations like Amazon have voted against unionization, sometimes out of fear that otherwise the company would shut their workplace down.

For decades, organizers have struggled to secure major unionization wins in the nation’s many union-scarce industries. Such efforts tend to come up short in part because U.S. law allows companies to deploy well-honed tactics to derail campaigns. They have included mandatory meetings where managers warn workers about the dire consequences of organizing.

Because the NLRB isn’t allowed to fine companies punitive damages, the penalties for firing workers in retaliation for organizing have usually been limited to things like posting a notice agreeing to follow the law, and reinstating the terminated activist with backpay, sometimes years after a campaign has already lost steam.

Even when a union wins a labor board election, companies aren’t required to make major concessions in negotiations, and in the majority of cases workers still haven’t secured a contract a year later, according to a 2009 study.

Victories in 2021 that unionized only a handful of workers, or improved non-union employees’ working conditions without unionizing anyone, could lay the groundwork for bigger future gains, said Seattle University labor law professor Charlotte Garden.

“Any time there’s a demonstration of workers’ collective power, that helps create the conditions for more workers’ collective action,” she said. But under the current legal system, she said, “unionizing really requires employees to take a leap of faith.”

Organized labor’s decades-long decline has meant that even unions’ victories have less impact on surrounding firms’ norms and standards, said labor historian Nelson Lichtenstein at University of California, Santa Barbara.

“Unions are definitely an island with high waters all around,” he said. “The managerial mindset for decades now has been that it’s cheap, advantageous and easy to stop unions, so just do it.”

Even hard-fought big public sector victories that unions have achieved in recent years, like the unionization of 17,000 University of California employees last year, underscore how much tougher organizing is for their private sector counterparts.

“Unions always can organize more, they can do more to empower their own members and build their own membership ranks,” said historian Lane Windham, associate director of Georgetown University’s Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor. “But within our current system that will not be enough.”

For half a century, each time Democrats controlled the White House and both branches of Congress, unions have pushed to overhaul labor laws, but each time they’ve come up short in the face of business opposition and the Senate’s 60-vote filibuster rule that some Democrats are committed to preserve.

“The path to formal union recognition and bargaining in this country is torture,” said former Communications Workers of America president Larry Cohen, who chairs the advocacy group Our Revolution.

Cohen said he still believes the trend of declining unionization that’s marked his whole career in organized labor will someday be reversed, through a mix of political and workplace movement-building.

“It will occur, but the forces against it are greater here than any other democracy in the world,” he said.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.