Mar 18, 2019

U.S. Treasuries Trade Like 1965 After Fed Kills Volatility

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s starting to feel like the world’s biggest bond market will never be exciting again.

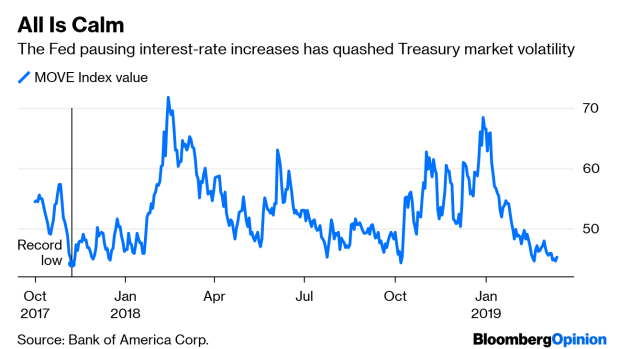

That’s an exaggeration, of course, but only slightly. Benchmark 10-year Treasury yields did fall to 2.58 percent on Friday, the lowest since January, only to climb back within their well-defined range. A few weeks ago, I asked if bond volatility was too quiet, given that Bank of America Corp.’s MOVE Index, which tracks price swings on U.S. Treasury options, was near the lowest since 1988. Turns out it wasn’t — the gauge fell to almost the exact same level last week.

Bond traders can thank Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell for these months of boredom. To give some context for just how contained Treasuries have been in 2019, consider this: Since Jan. 7, the first full session after Powell “pivoted” and signaled the central bank would pause indefinitely on interest-rate increases, the 10-year yield has fluctuated within a 22-basis-point range. That’s narrower than any calendar-year quarter since 1965.(1)

Bond traders, for their part, have basically thrown in the towel. “Favor selling 10yrs when they trade near 2.6%,” wrote Tom di Galoma, managing director of government trading and strategy at Seaport Global Holdings. But also, “U.S. money managers are targeting 2.7% as a decent buy level.” BMO Capital Markets noticed that trading volume in two-year Treasury notes on Wednesday was the lowest since the final days of 2018, when many desks are short-staffed. Bloomberg News’s Cameron Crise recently declared that “Treasury Bond Traders Are Just Too Good at Their Jobs.” On Thursday, he commented that “the Fed has just been brutally effective at crushing rates volatility.”

It seems like no one wants to test the range themselves, but they wish others would. “If you look at implied volatility from options on the longer part of the U.S. Treasury market, 10 and 30 years, it’s the lowest it’s been at in a decade, and that just makes absolutely no sense,” Gershon Distenfeld, co-head of fixed income at AllianceBernstein LP, said Thursday on Bloomberg TV. “The closest parallel you have to this, and it’s different in many ways, is probably the late `60s.”

There’s still time this month to shake things up, including by Powell himself – the Federal Open Market Committee is having its two-day meeting in Washington this week. But it’s hard to see what would cause a major move, given that there’s virtually no chance policy makers will alter interest rates. The only change might be to lower the group’s median expectation to one rate hike this year, rather than two. Some money managers have said the markets are “misinterpreting” the Fed. But officials haven’t really left room for interpretation at all in their unified guidance.

Meanwhile, the S&P 500 Index closed Friday at the highest since October, when 10-year Treasuries yielded close to 3.2 percent, rather than the current 2.6 percent. So it doesn’t seem like general risk appetite will push yields higher. Bets on a steeper yield curve have mostly gone nowhere, too, at least between two- and 10-year maturities.(2) The only winning wager has been going short volatility by selling options structures like strangles or straddles.

Sure, some major news one way or another on Brexit, a U.S.-China trade deal, or another stock-market collapse could end this lifeless Treasuries trading, but apart from that, it’s really starting to feel like the $15.8 trillion market is stuck in place until the Fed changes its tune. Of course, this is probably welcome news to the central bank, which has managed to tighten monetary policy far more than its peers over the past two years while keeping inflation in check.

Elsewhere in markets, equities seem to have forgotten their once-pressing concerns about the Fed’s balance-sheet reduction, and the average corporate-bond spread is near the narrowest since mid-November. Investors are turning sanguine about the risk of triple-B-rated debt, anticipating that companies will use this window to clean up their balance sheets. A large $4.2 billion leveraged-loan deal was able to cut pricing by 50 basis points in the face of what Bloomberg News’s Lisa Lee called “overwhelming demand,” even though lender protections were considered among the “worst ever.” In short, markets are riding the wave of steady interest rates.

Treasuries traders, on the other hand, may have to get used to floating along in a lazy river.

(1) Even including the first few trading days of 2019, when investors were still reeling from stock-market losses, this quarter is shaping up to have the second-tightest trading range of 10-year Treasuries since the 1970s.

(2) The yield curve from 5 to 30 years is the one exception. It reached the steepest level since February 2018.

To contact the author of this story: Brian Chappatta at bchappatta1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.