Aug 19, 2019

U.S. Treasury seizes the moment to revisit ultra-long bond proposal

, Bloomberg News

What trillions of dollars in negative-yielding debt means for markets

The odds on the U.S. Treasury’s ultra-longshot may just have narrowed.

Record-low interest rates make this an opportune time for the Treasury to revisit a proposal it’s shelved in the past: To issue the longest-term debt it can. So for the second time since U.S. President Donald Trump took office, the department is exploring the prospect of selling bonds due in 50 or 100 years, going way beyond the current three-decade maximum.

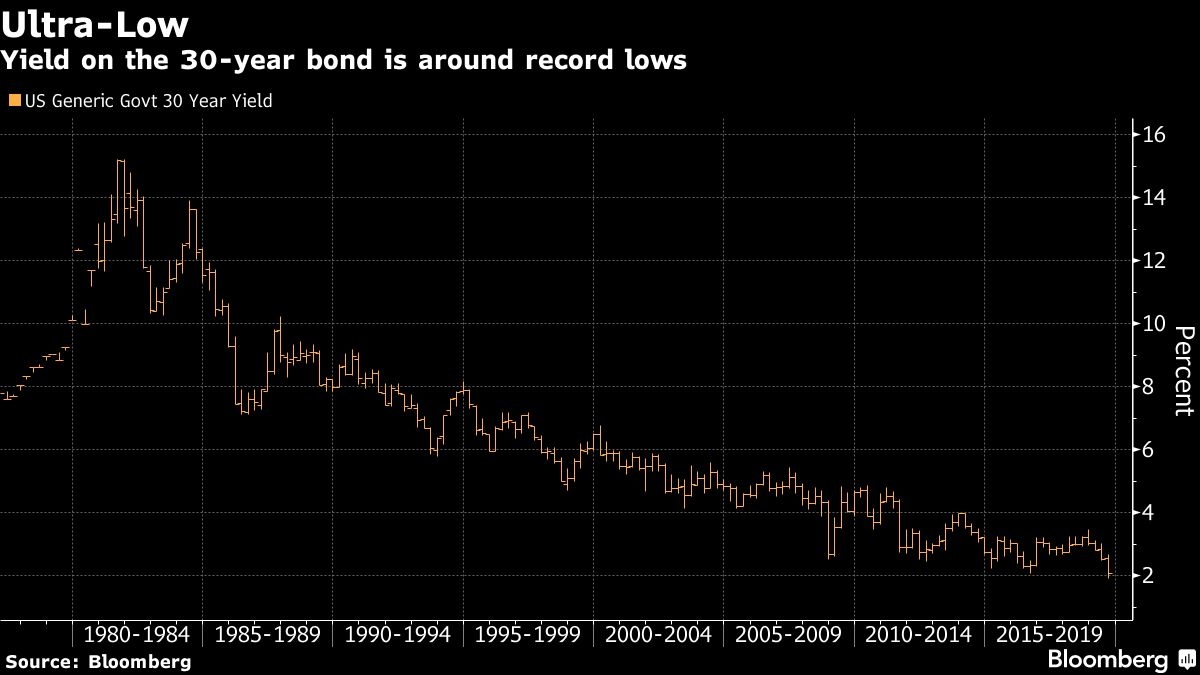

The idea has fallen flat in the past, but now might be its moment. The world’s spreading pile of negative-yielding securities — it’s at US$16.4 trillion and counting — is driving investors further out global yield curves, in part to finance retirees’ longer lifespans. The rate on 30-year U.S. government debt fell to an all-time low sub-two-per-cent last week. It’s now within about 60 basis points of what it would cost the Treasury to borrow for five years.

“The yield level for 30-year debt suggests there’s still demand for duration and I don’t think the Treasury expects that to change any time soon,” said Thomas Simons, senior money-markets economist at Jefferies in New York.

The last time Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin broached the issue, in 2017, the dealer community snubbed it. Jefferies was among the more-receptive to the proposal then, too. But Simons said the prospects may be better now given the “significant pivots” of central banks toward lower rates and monetary easing.

And from the Treasury’s perspective, the idea certainly seems timely as the department seeks to limit the cost to taxpayers of plugging a budget gap that’s headed to US$1 trillion annually.

“They might need an additional point on the curve to meet issuance needs,” said NatWest Markets rates strategist John Briggs. While he sees the rationale for an ultra-long bond, he said “there are no changes in the concerns I had in 2017.”

Any such move is a long way off, according to Simons. But the Treasury is clearly keen to test the waters, posting a note on its refunding website at the end of last week that the Office of Debt Management is “conducting broad outreach to refresh its understanding of market appetite” for 50- or 100-year bonds.

DEMAND QUESTIONS

Among the risks of the ultra-long bond is the ebb and flow of demand over the course of an economic cycle. Buyers may be enthusiastic when yields are high, but in downturns, when the Federal Reserve is cutting rates, demand could well evaporate, pushing government borrowing costs higher across the curve.

As a result, ultra-long bond auctions are likely to become “very tactical,” said Bank of America’s Bruno Braizinha, director of U.S. rates research.

“Demand is going to vary a lot,” he said. “Presumably you want to issue every year, you’re going to have auctions of these ultra-long bonds that are going to systematically fail in periods of ultra-low yields.”

That was the crux of Wall Street’s argument against the move the last time the Treasury broached the idea of ultra-long issuance. It received a cool reception as dealers said demand wasn’t sufficient to maintain the government’s goal of regular and predictable issuance.

For Briggs at NatWest, another risk is that 50- or 100-year debt could cannibalize demand for the 30-year. In 2017, some saw the potential for ultra-long issuance to further erode dealer margins that have been squeezed by automation and alternative sources of liquidity, by offering an alternative to the almost $300 billion market for zero-coupon Treasuries, known as Strips.

Instead, some analysts proposed reviving 20-year bonds, which were discontinued in 1986. The issue was included in the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee’s list in January of potential new securities the government might use to expand its investor base.

Given the voracious global demand for duration and the appeal of locking in low borrowing costs for generations, some observers see a window for the department to move forward in the face of Wall Street’s concerns.

“If rates remain at current levels, I could imagine the Treasury moving ahead with this,” said Lou Crandall, chief economist at Wrightson ICAP.