May 18, 2022

UK Inflation at a 40-Year High Engulfs Johnson and BOE in Crisis

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) --

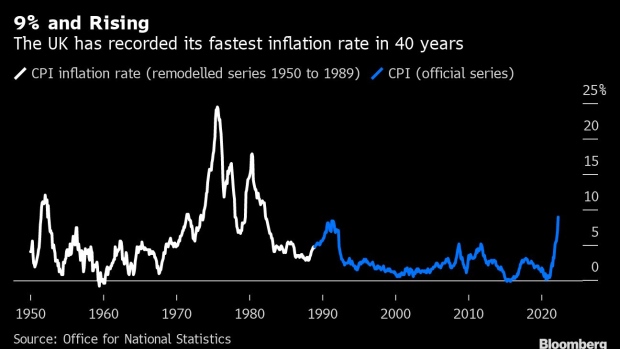

Britain’s worst bout of inflation in 40 years is quickly becoming a crisis both for Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government and the Bank of England.

The central bank is in the eye of the storm after consumer prices surged 9% in the year through April. Cabinet ministers, economists and even a former BOE boss are complaining that Governor Andrew Bailey was too slow to act and is failing in his job to keep inflation to 2%.

That finger-pointing may be meant to distract from rising pressure on Johnson’s administration to protect voters from the biggest squeeze on living standards in memory. Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak to date has targeted relief at those in work, while the Labour opposition says help should be extended to pensioners and those on benefits.

A YouGov Plc poll published on Tuesday found that a record 72% of those surveyed think the government is handling the economy badly, and three-quarters think it’s doing poorly with inflation. More than half of those who voted Conservative in 2019 faulted the government.

Bailey didn’t help matters by admitting this week he felt “helpless” in the face of global price pressures, warning of an “apocalyptic” surge in the cost of food. He has “run out of horsemen” after the pandemic, the war in Ukraine and the latest price shock, he said.

Even former senior BOE officials have weighed in. Andy Haldane, who warned about the inflation “tiger” until he stepped down as chief economist in August, said the BOE should have acted sooner. Mervyn King, who was governor through the financial crisis a decade ago, told LBC radio on Tuesday that officials “around the world made serious mistakes in not acting much sooner … including ours.”

That marked a rare breach of the unwritten code that past governors do not criticize their successors. What’s more surprising is the depth of the critique, with King calling last year’s dose of quantitative easing a mistake, with detailed reasoning.

“There was too much money chasing too few goods,” King said. Bailey is wrong to feel helpless, he added. “The second mistake was the belief that there’s not much we can do about the high energy and food prices.”

King argued that the BOE should be raising rates aggressively because imported prices determine future pay settlements. With more job vacancies than unemployed, the jobs market is tighter than it has ever been, creating the ideal conditions for a wage spiral.

“The idea that an interest rate of 1%, when wages are rising at anywhere between 5% and 7%, (is) going to have much impact on that inflation rate is really very strange,” King said.

In effect, he was telling the BOE to drive up unemployment. And that goes to the heart of the terrible dilemma the BOE faces: push people out of work now to prevent a wage price-spiral, or go easy and risk a long-term stagflationary slump.

The BOE’s mandate is clear that it should raise rates even if doing so runs the risk of a recession. What makes the crisis so tricky, and the politics so adversarial, is the fact that the solution from the BOE’s view point is very different to the one voters and politicians want.

From the BOE perspective, inflation is a technical problem that can be addressed with a technical response: rate rises and unwinding the vast stock of government bonds acquired by the central bank.

From the view of households and politicians, it is a human cost-of-living crisis that can only be addressed by handouts, potentially inflationary ones, from government. Monetary and political incentives are working at cross-purposes.

When politicians blame the BOE for failing to keep a lid on inflation, they may hope to deflect attention from their own shortcomings but they are in fact advocating for unemployment. Of course, they would never use those words, leaving responsibility for both the inflation shock and possible job losses with the BOE. It’s neither the fairest nor the cleverest approach but it’s not hard to see why ministers are looking for a scapegoat.

Tensions will only ratchet up because the crisis is going to get worse. Input prices, the costs producers bear, are rising at an annual rate of 18.6% -- the highest on record, and companies, as a BOE survey this month showed, are passing those on. Factory gate prices, the prices retailers pay, rose at the fastest rate since 2008. In October, energy bills will jump again. The BOE is forecasting inflation to peak at 10.2%. That is beginning to look optimistic.

Since the Spring Statement’s underwhelming package of measures, amid warnings that destitution levels could reach 1 million, the government has been under relentless pressure to do more for the poorest households, who are experiencing an inflation rate of 10.2% already, the Resolution Foundation think tank estimates.

Sunak is reported to be planning as much as £1 billion pounds of grants for low-income households through the Warm Home Discount, The Times newspaper reported. The paradox is that the more the BOE addresses the technical inflation shock by raising rates, the worse the cost-of-living crisis in the short term will get. Jobs will be lost, debt will be harder to service.

The hard truth, as King said, is that “people are stuck with this.” All the BOE can do is increase borrowing costs in an attempt to prevent inflation becoming embedded. All the government can do is redirect wealth, either in transfers through the tax system today or in borrowing and the cost that leaves for the taxpayers of tomorrow.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.