Oct 2, 2022

UK Pension Strategy That Gilt Market Relied On Becomes Big Risk

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The UK’s pension sector created the modern gilt market. Last week, it almost broke it.

For decades these investors have demanded long-dated assets to match their liabilities going out decades into the future, particularly for defined-benefit programs which need to make payouts irrespective of market moves. That’s been a boon to UK government finances, with the average maturity of the nation’s debt outstripping its peers.

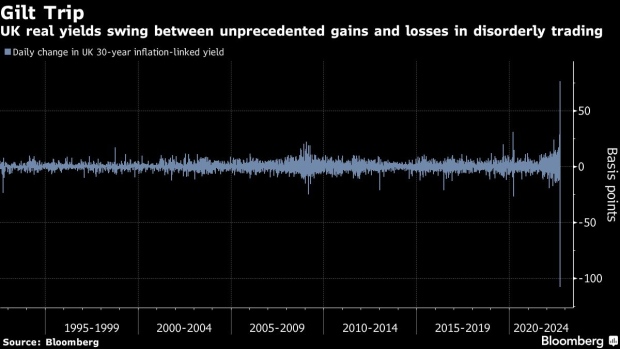

But last week, that symbiotic relationship started to unravel. The market saw new Prime Minister Liz Truss’s unfunded tax-cut policy as fiscally reckless. Pensions which pursued so-called liability-driven investment strategies with leverage faced emergency collateral calls on their hedges as government bond yields soared, resulting in the largest selloff in history. The Bank of England, which had been on a mission to reduce its balance sheet, was forced to start buying bonds again to calm the turmoil, sparking the greatest rally on record.

For investors whiplashed by this unprecedented volatility, the risk is the worst isn’t over. There’s no sign yet of a Truss u-turn ahead of a Conservative party conference this week, even with the pound having slumped briefly to a 37-year low. And for some, the long-lingering fragilities in the market remain exposed to another blowup.

“The challenge for the BOE is to ensure there are sufficient tools in place to maintain market functioning,” said Daniela Russell, head of UK rates strategy at HSBC, who predicted the need for an intervention last week. “It needs to recognize that the pressures on pension schemes have not suddenly disappeared.”

Pension fund demand for long-dated bonds and inflation-linked paper has been near-insatiable since the so-called minimum funding requirement came into force in 1997. The rules, which set valuation metrics to ensure a minimum level of solvency, have been followed by updates that have meant the appeal of such securities to the UK pension community remains high.

“It’s what makes gilts unique among global bond markets,” said David Parkinson, sterling rates product manager at RBC Capital Markets. “UK debt has a much longer average maturity than anywhere else because of that pension demand.”

Yet last week demand for long bonds collapsed. The yield on 30-year inflation-linked gilts -- favored by these pension funds due to its long maturity and its protection against price increases -- soared 76 basis points on Tuesday, a fresh record which eclipsed a 68 basis-point spike a day earlier. For context, both moves were more than double the previous largest jump recorded in March 2020.

Future Liabilities

On paper, the rise in yields is great for defined-benefit pension schemes. This is counter-intuitive, given they mostly hold bonds which fall in value as yields rise. Yet the value of their future liabilities is calculated in reference to market interest rates. When they rise, their funding status improves, other things being equal. At end-August, these funds had a solvency ratio of 125%, and the situation would have got even better since then given the sell-off in gilts, according to Bank of America analysts including Agne Stengeryte.

“These should be happy days for the defined-benefit pension system, with higher yields delivering record surpluses,” they said. “It‘s not quite like that.”

The problem stems from the speed and scale of recent yield moves and the leverage used by LDI strategies in order to hedge against higher rates. As rates spiked, they set off a chain of collateral calls. These aren’t strictly unusual -- the same funds had to post collateral earlier this year given the bond selloff -- but the pace of this market move triggered a full-blown crisis. Instead of weeks, they had just hours to post more cash.

The BOE intervention on Wednesday relieved the immediate pressures and has allowed markets to resume functioning, albeit with liquidity still strained. But it’s unclear whether its commitment to buy long bonds until Oct. 14 will be sufficient to stave off vulnerabilities, especially given it said it will start actively selling bonds into the market from the end of the month.

Exposed Funds

“The current purchases buy a little time, but it will take much longer for collateral pools to be adequately replenished, potentially leaving pension funds exposed in the meantime,” said HSBC’s Russell. “While some schemes are facing less pressure, for those that added interest-rate hedging on a leveraged basis when 30-year gilt yields were down close to 1%, current levels near 4% are unpalatable.”

Russell said one option would be to design a new backstop, taking inspiration from the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan. She proposes an ongoing commitment by the BOE to carry out purchases of long-dated UK government bonds on whatever scale is necessary to support market functioning, rather than the temporary program announced last week. That would be combined with a front-end skewed active quantitative-tightening program. The BOE could potentially only sell short- and medium- gilts from its portfolio, she proposed.

That might not be popular with investors who favor shorter maturities, with the long-end dominated by domestic pension funds and asset managers. And in any case, it doesn’t tackle the initial catalyst for the selloff: concern over the new government’s fiscal plans.

“Unfortunately, we believe the root cause of the problem -- which is the loss of confidence in UK fiscal policy -- will not be addressed” by the BOE’s intervention, said Rufaro Chiriseri, head of fixed income for the British Isles at RBC Wealth Management, who expects a further decline in gilts.

Long-Term Damage

It’s a view shared by others. More concerning is the long-term damage to the UK’s financial credibility with investors. Truss’s government signaled it’s sticking with its plan for tax cuts after a meeting Friday with the UK’s fiscal watchdog, damping market expectations that a policy U-turn might be imminent ahead of the ruling Conservative Party’s annual conference this week.

“I don’t think we’ve seen the peak in yields yet,” said Imogen Bachra, a strategist at NatWest. “Although the BOE interventions this week have served to calm markets and regain a sense of composure, I don’t think it materially alters the net supply outlook, which is really the driving force behind higher yields.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.