May 29, 2022

UK’s Credit Market Tells a Grim Story of a Looming Cash Crunch

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The sterling bond market is flashing red, with double-digit losses and borrowers put to flight.

That’s alarming for firms that need cash. They’re up against the Bank of England’s rate rises, a cost-of-living crisis with inflation at the highest in 40 years and the slow-burning legacy of low productivity. And then there’s the added fallout from Brexit. All in, Bloomberg Economics expects the economy to shrink 0.4% this quarter.

“It makes for a pretty tough set up,” said Justin Jewell, a high-yield portfolio manager at BlueBay Asset Management LLP. “The sterling market has been a bit unloved this year partly because of BOE rate hikes and partly because the UK economic outlook is looking the weakest out of the major economies.”

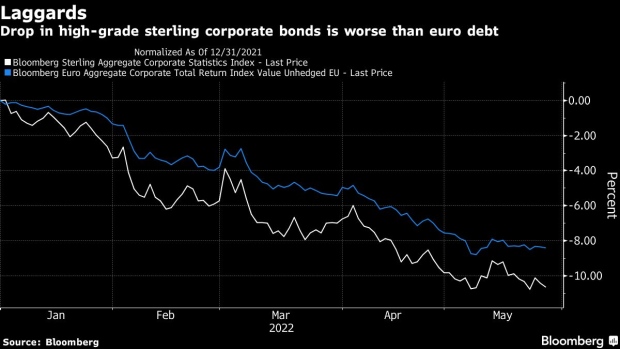

A Bloomberg index that tracks top-rated sterling securities, the bulk of which belong to companies based in the UK, has fallen 11% this year as of Thursday, two percentage points more than euro-denominated debt. The gauge’s market capitalization has shrunk £38 billion ($48 billion), the worst year-to-date contraction since at least 2000, which is as far back as the data goes.

On top of that, the market for new sterling corporate bonds, which is much smaller than its euro and dollar peers, has virtually ground to a halt. Issuance by UK-based, non-financial firms in 2022 is just £3.78 billion, the lowest since 2016 and a third of what was sold this time last year. Companies such as Matalan Ltd. are having to rethink their capital structure, and funding mergers and acquisitions is becoming tricky and expensive.

“UK corporates that need liquidity and are struggling with the inflationary environment may struggle to service their debts or raise more capital or keep their businesses going,” said Zachary Swabe, a portfolio manager at UBS Asset Management. “As sterling issuers refinance they will be forced to pay higher coupons, in some cases double and in others, even triple.”

That’s because borrowing costs have soared this year, with the yield on sterling high-grade company bonds skyrocketing about 160 basis points to 3.66% in May, the highest since 2016, according to a Bloomberg index. Yields are almost a percentage point above their 10-year average.

A deep dive into the gauge shows all the bonds that can be measured on a year-to-date basis are down in 2022. The biggest losers are some consumer credits, which dropped an average of 13%. A Bloomberg index of junk-rated sterling debt portrays a similar picture, with all but a handful of bonds dropping.

“Higher borrowing costs and a more challenging borrowing environment will inevitably add to growing margin pressures facing corporates, against the backdrop of weaker consumer demand,” said James Smith, an economist at ING. “It’s fair to say the SME space is more vulnerable, partly because they’re probably more vulnerable to the higher inflation backdrop, but also because debt levels increased much more substantially during Covid.”

Sterling corporate debt sales from domestic non-financial borrowers almost doubled in 2020 to £8.4 billion, and then rose again in 2021 to £10.7 billion, the highest since 2018, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Rampant inflation and the Bank of England’s string of interest-rate increases to the highest since 2009 are fueling the surge in corporate bond yields, but so is the prospect of slower economic growth and concern over corporate earnings. While the government’s recent package to help households cope with rising energy prices have reduced the risk of recession, growth will likely be lackluster.

Bloomberg Economics’s Dan Hanson expects gross domestic product to grow 0.3% in the third quarter, and shrink 0.3% in the last three months of the year. But he also says the government’s measures will prompt the BOE to hike rates four more times this year. That would send companies’ borrowing costs higher.

Market Swings

The threat of stagflation is driving up volatility for credit. A measure of market swings for sterling high-grade corporate bonds -- the 100-day historical volatility gauge -- is the highest since August 2020. That makes tapping the market a challenge, and it’s one reason why bankers are nervous about committing to funding deals backing mergers and acquisitions.

Take the sale of Boots chemist, a high-street staple. Before the Issa brothers, who were bidding together with TDR Capital, mulled walking away from talks, they and the rival consortium -- Indian tycoon Mukesh Ambani and buyout firm Apollo Global Management Inc -- hadn’t yet secured binding financing deals from banks.

One of the deterrents for lenders is the fact that banks have a staggering $20 billion of debt that they underwrote to fund buyouts, which they can’t get off their balance sheets because of the rising cost of money, and waning appetite for risk.

If markets weren’t so volatile, banks would probably be racing to provide the cash. But they’ve seen the struggles their peers continue to face with WM Morrison Supermarkets Plc, which was underwritten in August, when borrowing costs were considerably lower. Earlier this month, banks had to delay the sale of more than $2 billion worth of debt backing the buyout of UK bookmaker William Hill Ltd.’s international assets.

Those issues are diminishing the appeal of UK assets for private equity firms.

“The job of private equity is to buy stuff at the cheap part of the cycle,” said UBS’s Swabe. “PE still has the luxury of time and a worsening of the UK economy will unfold before they pounce.”

But for a handful of investors, the drop in corporate bond prices is an opportunity to hunt for bargains, particularly for those who think rate hikes are already priced in.

Some of the valuations are starting to look attractive, according to Paola Binns, a senior fund manager at Royal London Asset Management. That’s only “if you have the ability to not lose your nerve.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.