Jun 24, 2022

Ukraine Budget Lifeline at Risk as Biggest Bond Buyer Gets Antsy

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Ukraine’s war-battered budget is coming under more strain as the central bank increasingly raises the alarm about the limits of its ability to provide cash through sovereign debt buying.

The dilemma shows the difficult choices for policy makers in Kyiv as Russian forces have destroyed cities, blockaded the nation’s grain exports and displaced more than 10 million people. The economic fallout has brought budget funding for everything from pensions to military operations to breaking point.

The country’s government and the National Bank of Ukraine are locked in a row over how much more cash the central bank can print without stoking inflation or a collapse in foreign reserves, although some progress has been made in talks this week, according to people familiar with the discussions, who asked not to be identified because the negotiations aren’t public.

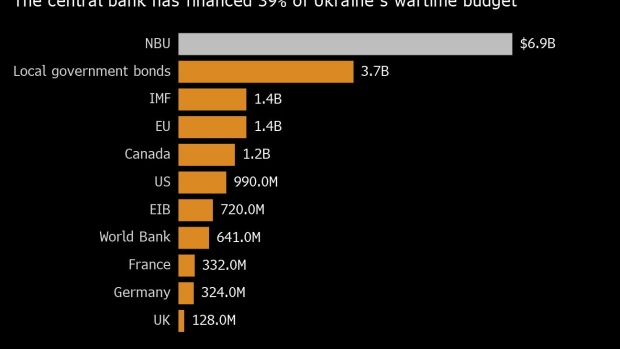

Since Russia’s invasion began four months ago, the NBU has financed 39% of Ukraine’s budget and the central bank has publicly piled pressure on the Finance Ministry to find other buyers for its war bonds. The concern is that this dependency will grow as the war cuts off key sources of revenue, investor demand for Ukraine’s bonds fizzles and foreign aid trickles in too slowly to cover the gaping budget hole.

Privately, central bankers say the bank can continue to provide funds for the war effort but is resistant to helping roll over or servicing government debt, according to one of the people. In a bid to ease the standoff and lure more financial investors, President Volodymyr Zelenskiy’s government agreed to consider increasing yields on its debt, the people said.

The thorny issue makes Ukraine even more reliant on timely access to foreign aid, the people said.

“There’s not very much Ukraine can do right now,” Timothy Ash, a senior emerging-market sovereign strategist at BlueBay Asset Management, said in an interview. “It has to pay the military, otherwise it dies. Their options are to print money, run down foreign reserves and hope that eventually the money from the West does come.”

International financial institutions along with bilateral agreements and grants have jointly provided another 40% of Ukraine’s wartime funding, with bond sales to investors other than the NBU accounting for the remaining 21%, official data show.

‘Crucial Imports’

Ukraine’s budget is increasingly strained with the war triggering an exodus of refugees, destroying factories and slashing state revenues to less than a third of government outlays. Russian blockades have cut off most of Ukraine’s agriculture exports at the country’s Black Sea ports, while additional military spending has tripled monthly state expenditures since the war began.

The central bank has stepped in with bond purchases and has become the provider of dollars and euros for “crucial imports,” a list that initially including fuel and weapons but has expanded to other goods -- to the chagrin of central bankers. This has drained Ukraine’s reserves by $3 billion to around $25 billion while inflation has accelerated to 18%.

Foreign currency sales have “significantly increased” in past weeks in what is largely a reaction to the “growing amount of money printed to shore up the state budget,” NBU Deputy Governor Serhiy Nikolaychuk told reporters on Tuesday. “Deficit financing should be first and foremost covered by external revenues and finance ministry debt sales on the market.”

The central bank bolstered its key interest rate to 25% from 10% this month in a bid to help the hryvnia and prompt an increase in government bond yields. But the Finance Ministry has until now been reluctant to boost the coupons on its war bond from between 9.5% and 11.5%, saying the cost of making them attractive to new investors would be too high.According to the latest deal, the ministry signaled it’s ready to test market demand at higher yields, although it’s not yet clear how much it’s willing to raise coupons or when, the people said.

In the three weeks since the emergency rate hike, Ukraine raised a total of 2.3 billion hryvnia ($79 million) of its once-popular hryvnia-denominated war bonds, a fraction of what it sold during the early stages of the conflict.

This has forced the finance ministry to rely more on foreign-currency bills and short-duration securities designated for non-military needs. Its buyers often include state-controlled commercial lenders that treat the investment as part of the government’s rollover strategy, rather than purely for profit, the people said.

“We hope the situation stabilizes soon and that we will be in a position to return to market rates,” Yuri Butsa, the Finance Ministry’s debt chief, said in an e-mailed response to a query. At that point, inflation and the Ukrainian currency will be relatively stable, also “thanks to proactive monetary policy,” he said.

Meanwhile, Ukraine’s dollar bond due in 2033 is trading around 32 cents on the dollar, below levels indicating distress and restructuring risk. Nevertheless, the government has said it will honor foreign-debt obligations even as it faces a $1.4 billion redemption and interest payment on Sept. 1, according to Bloomberg calculations.

The government has some reserves for 2022. Its bond-sale cap for the NBU stands at 400 billion hryvnia, nearly twice the amount the central bank has already bought, while it expects a total of $23 billion in international aid flows.

According to Olena Bilan, chief economist at Kyiv-based investment firm Dragon Capital, central bank budget support should be at least halved from the current pace of $1.7 billion to $2.4 billion per month to mitigate currency risk and ensure the country’s reserves aren’t drained.

“While it is acceptable for a central bank to support the budget during war, such funding should be considered as a last resort, not routine,” she said by e-mail.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.