Nov 1, 2022

Ukraine Supply to Take Spotlight at Bali Palm Oil Conference

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The supply outlook for cooking oil will be a hot topic at a conference in Indonesia this week after Russia suspended its participation in a pact to ensure safe transit of ships carrying grain and foodstuffs from Ukraine.

Ukraine accounted for almost half of the world’s sunflower oil exports before the Russian invasion in February. The war choked off that supply, and helped drive prices of palm oil, the most consumed edible oil used in everything from margarine to ice cream and shampoo, to a record close in April. Indonesia is the top global supplier of palm oil and Malaysia is the No. 2 producer.

Other topics are the increasingly volatile weather, the viability of biofuels in a year when food costs hit a record, and government policy in Indonesia, which roiled the market this year by imposing a temporary ban on exports. Analysts Dorab Mistry, James Fry and Thomas Mielke also present their outlooks at the conference, which is on Nov. 3-4. Here’s a closer look at likely talking points:

1. Russia’s War in Ukraine

Russia’s move to halt participation in a UN-brokered pact that allows exports of crops, including sunflower oil, from Ukrainian ports through a safe corridor in the Black Sea is the latest threat to global food security. It’s a further manifestation of the deepening geopolitical tensions that are sending shock waves through food supply chains still recovering from the pandemic.

The war in Ukraine has already skewed global trade flows of grains and oilseeds, raising longer-term questions about the availability of supplies from the Black Sea. A prolonged conflict will likely make those changes permanent, paving the way for palm oil to expand market share in places like India and China, where supplies of sunflower oil from Ukraine have dried up, according to Anilkumar Bagani, head of research at Mumbai-based Sunvin Group.

India, the largest importing country for palm oil, sunflower oil and soybean oil, is at the center of the struggle for market share. On top of all that, the potential for lasting Covid restrictions in China, and fears of a looming global economic recession, will probably keep the market volatile in coming months.

2. Weather Watch

La Nina is returning for a third year. The climate phenomenon occurs when the surface of the Pacific Ocean along the equator cools and the atmosphere above it reacts. This usually brings more rains to oil-palm regions in Indonesia and Malaysia, and drier conditions to soybean and corn areas in Argentina and Brazil. The event could spur flooding in Southeast Asia and hurt soybean crops in South America, said Oscar Tjakra, a senior analyst at Rabobank in Singapore.

If La Nina Persists, Expect More Drought and Flooding: QuickTake

Meteorological departments in Indonesia and Malaysia have warned about the risk of heavy rain and floods during the year-end monsoon season. Indonesia’s weather agency forecast an early rainy season this year in most of its regions with extreme weather during October and November. Prolonged floods will disrupt harvesting and transport of palm fruit, as well as reduce oil quality.

3. Indonesian Export and Biofuel Policy

Top shipper Indonesia flip-flopped this year on a controversial export ban and domestic sales rule, designed to cool the home market. Local supply ballooned as a result, which forced the government to reverse tack and ramp up exports by offering levy waivers that are in place through the end of the year.

Investors are focused on the fate of the domestic market obligation, which requires local producers to sell a portion of their output on the home market. The country in August raised the amount producers can export to nine times the domestic sales requirement from seven times, so they can now ship more.

Indonesia’s biodiesel plans are also in the limelight. The country has the highest volume of blending in the world with a mix of 30% palm with 70% diesel, the B30 mandate. The government will complete road tests in December to raise the mix to 40%. If successful, B40 will divert more palm to fuel and less to exports, potentially driving up food costs. By contrast, Malaysia is slowing implementation of B20 in transport to prioritize palm supply for food.

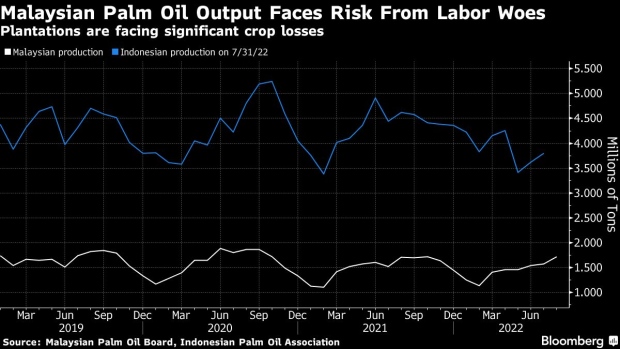

4. Malaysia’s Worker Shortage

Worsened by the pandemic, Malaysia’s chronic labor crunch is a big source of frustration. The largest group of growers forecasts production will shrink for a third consecutive year as a shortage of workers hampers harvesting and results in billions of dollars of crop losses. Unlike Indonesia, the No. 2 grower relies on overseas workers and the shortage has become progressively worse.

Although the government has approved some applications for foreign worker quotas, growers say there are still administrative and procedural glitches that cause delays. Meanwhile, Malaysia’s plan to impose a multi-tier levy system for foreign labor could further raise costs for plantation companies.

5. Sustainability

Increased scrutiny on sustainability and ESG practices is a lively debate for palm, which has been shrouded in controversy over allegations ranging from deforestation to open burning and forced labor. Sustainability solutions may have taken a back seat during the pandemic, but they will be thrown into the limelight again as the European Union reviews its Renewable Energy Directive and increases its ambition to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Particularly worrisome is the European Parliament’s latest proposal to advance the deadline for phasing out palm-based biofuels much earlier than the initial target of 2030. That would jeopardize palm as a biodiesel feedstock, as it could prompt European member states to adopt legislation that excludes the oil from renewable energy targets, or even from being used as a biofuel at all.

A sustainable vegetable oil conference is taking place at the same time as the main gathering this week. On the schedule is the Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries, and ministers from Indonesia, China, India, Russia and Ukraine.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.