May 17, 2020

Unpriceable Risk of Climate Change Stalks $31 Trillion of Debt

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- When English vineyards started producing sparkling wine that aficionados lauded as a rival to Champagne, Jack McIntyre took note.

“England was suddenly growing grapes that typically grew in warmer climes,” said McIntyre, a three-decade investment veteran at Philadelphia-based Brandywine Global Investment Management. “No doubt temperatures are rising -- how you properly price climate change in rates markets though, I have no answer for yet.”

He’s not alone.

Across continents, bond investors are struggling to answer what Deutsche Bank AG strategists dubbed “the question of our age” -- how much societies are willing to sacrifice in economic growth to counter climate change, and what that spells for the world’s $31 trillion sovereign debt market.

“It’s frankly very difficult to answer,” said Shamik Dhar, London-based chief economist for BNY Mellon Investment Management. “Some of the worst aspects of climate change haven’t been priced.”

The stakes have never been higher. Governments are selling debt at a breakneck pace to fund titanic stimulus and investors are desperate for income in a world where nearly $12 trillion of debt has negative yields. That means that even lower-rated countries can sell bonds that won’t mature for a century, a timescale far beyond any tested model for climate risk.

Even junk-rated Argentina, a hotspot for climate change, has managed to pull off the sale of century bonds in recent years.

While some investors have managed to factor climate change into stocks and corporate bonds, the long-term effects of global warming and other factors on an entire economy make it difficult to apply the same models to government debt.

“When markets find it difficult to price the risk, they just don’t price it at all.”

“We don’t have enough data to price the risk on a macro level over a long-term horizon,” said Shaun Roache, Asia-Pacific chief economist at S&P Global Ratings. “We don’t know the magnitude of the next shock, or how big the next bushfire will be or its impact on the economy,” said Roache, who was formerly a macro strategist at Singapore sovereign wealth fund Temasek Holdings. “When markets find it difficult to price the risk, they just don’t price it at all.”

Experts point to green bonds -- debt raised by companies and governments specifically for environmentally-conscious projects -- or climate bonds as ways to mitigate climate catastrophe risk.

But even with record growth in 2019 as green bond sales topped $217 billion, the amount is a mere drop in the world’s debt market. It falls well short of meeting the ongoing needs of investors and doesn’t help them pricing climate risk into sovereign bonds.

Climate change has long been on the radars of the world’s top central bankers, though they don’t all agree on their part in dealing with it.

Central Banks

In a 2019 speech, Reserve Bank of Australia Deputy Governor Guy Debelle examined how monetary policy is able to adjust to climate-related shocks and how the bank can weave climate change into its economic modeling.

The European Central Bank is looking for ways to favor environmentally friendly bonds in its monetary policy while U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has dodged questions on the Fed’s role, arguing that “climate risk is a very important issue that Congress has largely assigned to other agencies.”

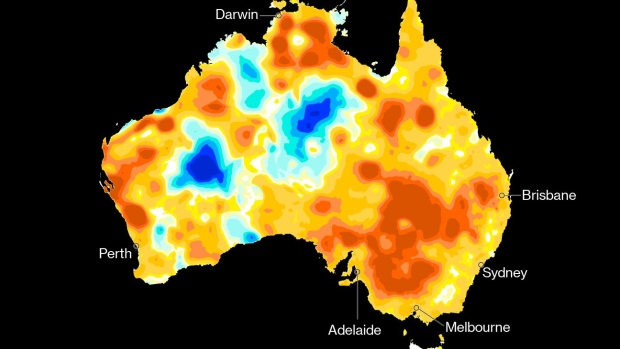

Perhaps nowhere was this risk more evident recently than in Australia, where a devastating wildfire season killed over 30 people, released up to 1.2 billion tons of carbon dioxide and saw 14% of the population affected.

As wildfires scorched an area the size of England in January, analysts struggled to accurately quantify the long-term financial impact across the economy. The Australian dollar slid more than 4% in the month. Yet bonds rose.

Yields on 10-year notes tumbled 42 basis points during the same period as investors sought shelter in government debt amid a deepening toll from the fires and virus epidemic.

“Typically investors have not been very good at quantifying these factors -- whether it’s a breakout of a virus or the effect of weather patterns into the long-term investment scenario,” said Tano Pelosi, portfolio manager at Antares Capital in Sydney. “It’s inevitable though that there’s an imposture of cost that has to be sheltered either by government or businesses, or most likely both.”

Regional governments may provide a better starting point for quantifying the cost of climate change in many countries, according to John Manning, a senior credit officer at Moody’s Investors Service in Sydney.

“It’s the states that have to first go out and fight the fires,” said Manning. “And it’s the farmers, the public health systems. It’s effectively a state-cost.”

Until adequate modeling is available, investors may have little choice but to continue piling into high-quality government bonds, even though climate risk looms ever larger over some of these securities, according to Chris Rands, a money manager at Nikko Asset Management Ltd. in Sydney.

“If it’s an event that’s going to occur again and again say over the next decade, then that’s when you have to step back and ask ‘how concerned should we be of the future?’,” he said. “If GDP is slowing and the economy is going to follow, then ironically, owning rates makes sense.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by Brandywine’s McIntyre.

“The challenge is investors are managed on a quarter-by-quarter basis, but the conversation about climate is a decade-long one, or even longer,” he said. “Rates like U.S. Treasuries still offer protection even as the debate on climate goes on -- but yes, it’s a tough one.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.