Jun 1, 2022

Utility Bills Surge 100-Fold as Venezuela Slashes Subsidies

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Venezuela’s government is quietly rolling back a decades-long policy of subsidizing electricity, water, gas and road tolls to shore up fiscal accounts, shifting the costs to businesses and individuals long accustomed to cheap utilities.

Across the South American country, light and water bills are rising. Tolls have been reinstated in several states. Gasoline stations are increasingly charging US dollars. And Nicolas Maduro’s government is ceding control of the sale of cooking gas and the levying of taxes to municipalities.

“We’re a different country now,” said Gustavo Nouel, an agronomist on a 197-acre rice farm in the grain-producing state of Portuguesa, where the electricity bill jumped 100-fold to $5,000 a month in January. “We’re in the middle of a transition because we killed the goose that laid the golden egg.”

Venezuela’s goose, an oil industry built atop the world’s largest proven reserves, is producing one-fourth of what it once did, leaving tens of billions of dollars less of revenue to spend on social services and programs for citizens. That’s forced Maduro to move toward a more capitalistic approach, which has helped spark a nascent economic recovery. Now, his government is gradually raising the price of state-provided services to closer to their actual cost -- while still trying to protect the more than 90% of the population that lives below the poverty line.

After years of recession and hyperinflation, which only recently ended, Maduro’s policy of allowing state-owned companies to charge more should help them to improve their operations and finances and pay higher salaries, said Jose Luis Saboin, an economic consultant in Washington, D.C., who studies the subsidies.

“It’s quite unfortunate that it has taken an economic catastrophe for this price situation to be reversed,” he said. “But as the saying goes: better late than never.”

To be clear, Venezuela is still cheap: a kilowatt hour of electricity is about a penny, compared to around 11 cents in the US. Still, it’s a dramatic turnaround for a government that long prided itself on providing utilities for next to nothing.

The policy dates to the 1970s when the government began subsidizing most utilities via the FX exchange rate, using the bounty from high commodity prices. It was kept in place under Maduro’s predecessor Hugo Chavez, who vowed to reduce poverty and let millions of households draw on services without paying. Even today, about one-third of the population has electricity or water hook-ups but doesn’t pay a dime, according to the National Observatory of Public Services.

Exactly how much the government is spending on the subsidies is unclear as reliable figures are not published. Economists at the Center of Public Policy at IESA, a Caracas-based business school, estimate they amounted to $25 billion annually as recently as 2014.

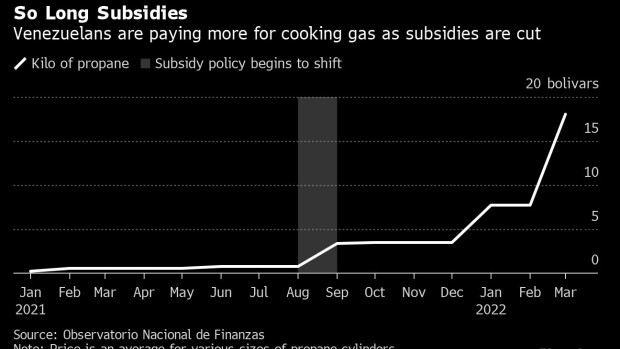

Maduro began shifting the policy in earnest in 2020, targeting everything from cooking fuel to electricity rates. Many gasoline stations moved from charging in bolivars to US dollars as the government was forced to start importing condensate from as far away as Iran to mix with local crude.

But the change, which occurs as many governments around the world increase subsidies to soften the blow of surging energy and food prices, has come with little fanfare or publicity, which has helped Maduro avoid facing a public backlash. Merchants say they were blindsided by huge bills. Services, meanwhile, have remained lousy.

“We used to pay cheap prices for inefficient services, now we’re paying high prices for the same inefficient services,” said Omar Bautista, head of Venezuelan autoparts manufacturers association, FAVENPA. He said manufacturers have been hampered by the frequent rationing of water and energy outside of Caracas.

Some producers have adapted by increasing prices or moving to cheaper municipalities run by government-backed mayors that are luring businesses with tax exemptions. Others have had to close shop and sell.

In Barquisimeto, the biggest agribusiness city in western Venezuela, Francisco D’Armata, is considering moving his 45-year-old glass manufacturer business to a location where services are more dependable and the local government has kept the taxes lower to bring back industry.

“I’d like my son to extend this business to a third generation, but conditions are still tough. We hold high hopes things will get better,” he said.

For Simon Salas, director at the business association of Lara, Venezuela’s agribusiness craddle, the hikes make sense, considering the shifts underway in the country.

“We’re just getting real, whether we like it or not. Venezuela is entering unchartered waters, transforming itself,” he said. “We were paying almost zero for the services, so we can’t compare.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.