Sep 22, 2021

Venezuela Debt Swap Breathes Life Into All-But-Dead Bond Market

, Bloomberg News

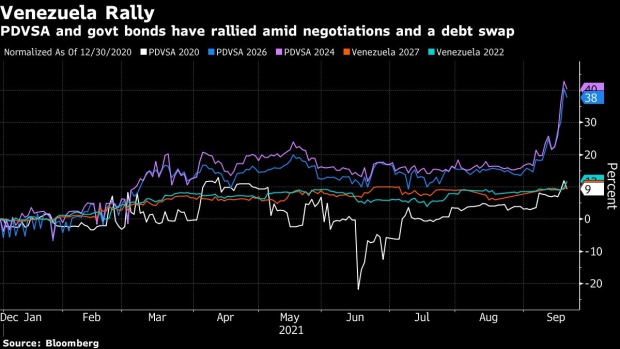

(Bloomberg) -- The market for Venezuela’s defaulted bonds is coming back to life as traders bet that the government’s move to swap a stake in a Caribbean refinery to settle some of its obligations could portend more deals to come.

Volumes are still small, limited by sanctions that prevent U.S. investors from buying the notes. But when securities come up for sale they’re almost immediately snapped up, mostly by European funds with a significant tolerance for risk. Prices of bonds from state-owned oil producer Petroleos de Venezuela have climbed as much as 17% over the past month -- though they remain deep in distressed levels at about 5.25 cents on the dollar. Sovereign bonds are up about 20% to 11 cents, according to brokers and term sheets seen by Bloomberg.

It’s a turnaround from recent years, when the debt was basically left to rot on balance sheets amid sanctions imposed by the Trump administration in 2018 that prevented any kind of traditional restructuring. Now hopes have been revived with the swap for the refinery, called Refidomsa, the first tangible evidence that President Nicolas Maduro’s government is prepared to start chipping away at the delinquent bonds -- which, at $80 billion with interest, is among the world’s biggest piles of defaulted obligations.

Further buoying prices, government and opposition representatives are holding negotiations in Mexico in an attempt to end a years-long political stalemate.

Investors’ “views have changed for the better on the government’s willingness to seriously negotiate with the opposition leaders and to take the necessary steps to give the Biden administration reasons to loosen sanctions,” said Dean Tyler, head of global markets at London-based BancTrust.

Recent bond trading volumes are the highest since sanctions were imposed as buyers built up positions ahead of the political negotiations. “The Refidomsa swap helped to stimulate demand as it underscored Venezuela’s willingness to engage,” he said.

Under the deal completed in August, the government gave investors its 49% stake in the Dominican refinery -- valued at about $88 million -- to settle about $361 million of old government and Pdvsa bonds. The so-called debt-for-equity swap effectively priced the bonds near 24 cents on the dollar.

The particular circumstances surrounding the swap suggest it could be hard to replicate with other Venezuelan assets. The transaction was complicated -- involving Pdvsa, the governments of Venezuela and the Dominican Republic and a wealthy family that had bonds it needed to get rid of. U.S. Treasury officials were briefed on the operation and didn’t object.

On paper, the Venezuelan government has about $6 billion worth of other foreign assets it could offer creditors, according to Guillermo Guerrero, a strategist at Emfi Group Ltd. who tracks the properties.

The list includes stakes in refineries in Cuba and Saint Lucia, parts of insurance and marketing companies in Aruba and Bermuda, accounts receivable from its years of sending crude to Caribbean countries as aid, a piece of Uruguayan bank Bandes, a fertilizer plant in Colombia, a mining company in Spain and an aluminum manufacturing plant in Costa Rica.

But as investors scour the list of what the Venezuelan government owns, they may find questions over valuations, how to work around U.S. sanctions and the fact that some foreign governments recognize Juan Guaido as the country’s interim president.

Jose Ignacio Hernandez, a former state prosecutor appointed by Guaido to protect Venezuela’s assets abroad from creditors, said very few of the assets are unencumbered.

Still, the most daring creditors see the potential for profit. They’re also eyeing possible swaps for local assets, such as companies that were expropriated by the government, and stakes in petroleum joint ventures and concessions.

Requests for comment from the government’s communications ministry weren’t returned.

Reduce Stock

Maduro has publicly stated his government wants to make good on its overseas obligations, which it began defaulting on in 2017. He has blamed the impact of U.S. sanctions for the country’s spiraling economy and for preventing the government from paying down and restructuring obligations.

“I have the plan,” Maduro said during an interview with Bloomberg TV in June. “Our executive vice president, minister of finance, has presented the plan to the holders. They know that we are willing. They know that our plan is viable.”

While the government has not revealed details of the strategy, it could use swaps to reduce the debt stock before sitting down to discuss a larger restructuring, which is likely years away and would first require the lifting of U.S. sanctions.

Optimism is low that the political negotiations -- which resume Friday in Mexico -- will result in a breakthrough agreement. But the fact that the sides are even meeting has raised the prospects that the U.S. government -- which is closely monitoring the talks -- might start to reconsider some restrictions.

That is also helping to lift bond prices, with a PDVSA note that matured in 2020, backed by shares of the U.S.-based Venezuelan refiner Citgo, rallying to as high as 28.5 cents on the dollar.

“The government knows that it can’t restructure its debt until sanctions are lifted,” said Francisco Rodriguez, an economist and fellow at the Council of Foreign Relations who formerly served as head of Venezuela’s congressional budget office. “Anything they can do now when prices are low to retire some of the debt is going to place them in a better position for a restructuring.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.