Dec 6, 2022

Venezuela’s Private Lenders Blossom in Land of $1 Credit Card Limits

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The amounts are so small that in most places they’d go on a credit card -- a few hundred dollars to buy an appliance, or a few thousand to stock a corner store’s shelves. Except, in Venezuela card limits can be as low as $1, and banks severely curtailed lending years ago.

So a cottage industry of at least half a dozen shadow lenders has sprung up to make short-term loans at monthly interest rates of as high as 5%. Catering to Venezuela’s middle and lower classes, as well as mom-and-pop enterprises, the startups are filling a void and helping fuel the country’s tentative economic rebound.

The industry is minuscule by international standards, but in a country where gross domestic product has shriveled 80% in the past decade, even a loan of a few hundred dollars can make a huge difference to a budding entrepreneur or a family in need of a new refrigerator.

The rapid growth of these private lenders shows the pent-up demand for credit as an uneven recovery takes hold following the government’s decision to allow the dollar to be used in everyday transactions, which created some stability for Venezuelans stung by years of brutal inflation as the local currency collapsed.

“Since we are seeing an improvement in Venezuela, we’ve decided to increase our bet,” said Gabriel Castillo, the chief executive officer of Ribo Capital, a firm based in the Dominican Republic that began offering loans in Caracas late last year. “Dollars have reached all social levels.”

Ribo has about 400 loans outstanding, with an average term of 12 months, up from just 50 loans when the business started in December, according to Castillo. Part of its business comes from partnering with local companies to offer payroll loans for their employees.

One challenge for the smaller lenders is figuring out whether a particular borrower is likely to pay them back. After years of economic turmoil including a brutal recession and US sanctions, credit histories have all but vanished, leaving lenders hamstrung.

So firms have developed their own scoring tools to judge the likelihood of getting paid back. Some track metadata from mobile phones to look for usage patterns that portend a high likelihood of users paying back loans, while others administer psychological tests intended to measure traits like spending impulsiveness and the desire to save money.

No Defaults

That’s the method employed by Caracas-based AlAlza Inversiones, which recently started a project called Pidelo to offer small loans to businesses and corner shops in a notorious slum in eastern Caracas known as Petare. The company issued 200 loans in its first two months with interest rates ranging from 3% to 5% a month and a maximum repayment period of 90 days.

So far, no one has defaulted on the loans, which average about $500, according to Daniel Berconsky, Pidelo’s CEO.

Cashea, another startup, has introduced a mobile-phone app that consumers can use at participating stores to purchase items on credit. The firm has signed deals with 26 retailers since October and says it’s had zero defaults.

While no one disputes that there’s been a boom in lending in Venezuela relative to the dearth of credit available in recent years, hard data is elusive. The country is a credit wasteland, with even the government cut off from borrowing after defaulting on its bonds five years ago.

Lack of Data

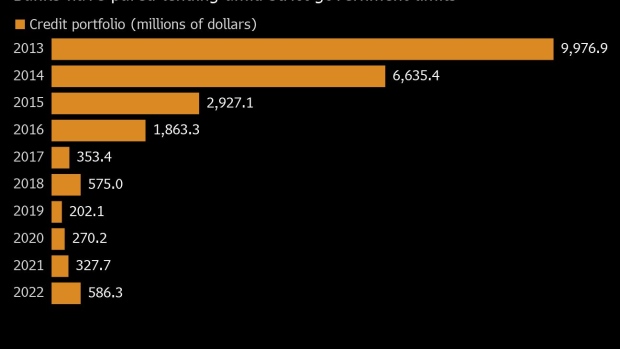

There is no public information on how many private lenders operate in Venezuela, and no one keeps track of average interest rates, loan sizes or typical customer profiles. And while the official banking system’s credit portfolio is a little over $650 million, less than 4% of that is consumer credit, according to Caracas-based banking consultancy Aristimuño, Herrera & Asociados. That compares with about 30% in neighboring Colombia.

Both banks and the credit-card industry were discouraged from consumer lending by government officials who feared it would reignite inflation. That’s resulted in many credit cards carrying limits of just about $50, although some offer less than $1 in credit.

The lending industry could be even bigger, but investors are hesitating because of the lack of clear rules and the uncertain outlook for the economy, according to Carlos Aguilo, director of private capital association Venecapital and founder of a tech startup incubator. Until more non-bank lenders get up and running, unmet demand for credit will be filled by informal lenders -- often loan sharks -- that charge prohibitive fees of up to 20% a month.

The lack of lending stems in part from President Nicolas Maduro’s efforts to clamp down on inflation in years past, when he restricted banks’ ability to extend credit. Consumers were the most affected by the ban.

“Unsecured loans are a segment that Venezuela lost track of more than 10 years ago,” said Pedro Vallenilla, the CEO of Cashea. “It is a great opportunity.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.