Sep 29, 2019

Wall Street falls in love again with companies loaded up on debt

, Bloomberg News

The Federal Reserve’s new round of interest-rate reductions just might be working. At least, that’s what one obscure, but key, stock market indicator suggests.

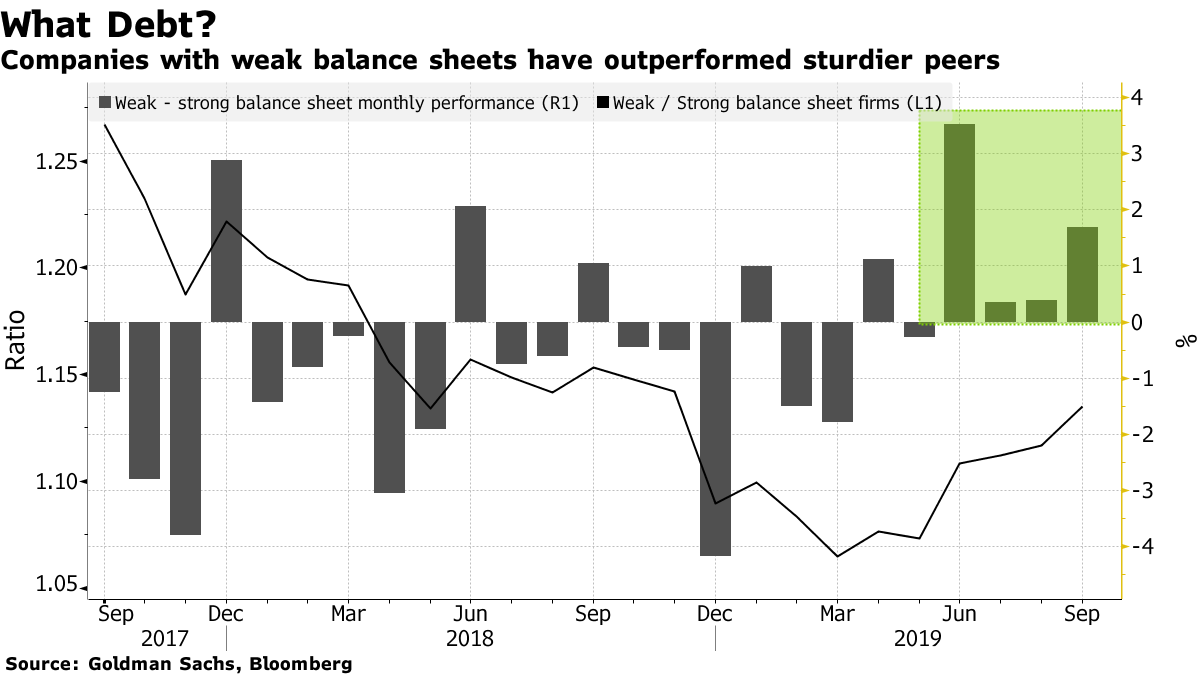

For the first time since 2016, companies with fragile balance sheets are outperforming their sturdier peers and the broad market, a pair of Goldman Sachs indexes show. That’s a clear sign that the rate cuts are shoring up investor confidence in heavily indebted companies -- the segment of corporate America that’s perhaps most at risk to any downturn that hits the U.S. economy.

The outperformance is so stark that a pure measure of leverage is the top equity factor this year among 10 styles tracked by Bloomberg. It’s a big turnaround for traders who had recently pushed relative valuations for financially solid firms to a 16-year high.

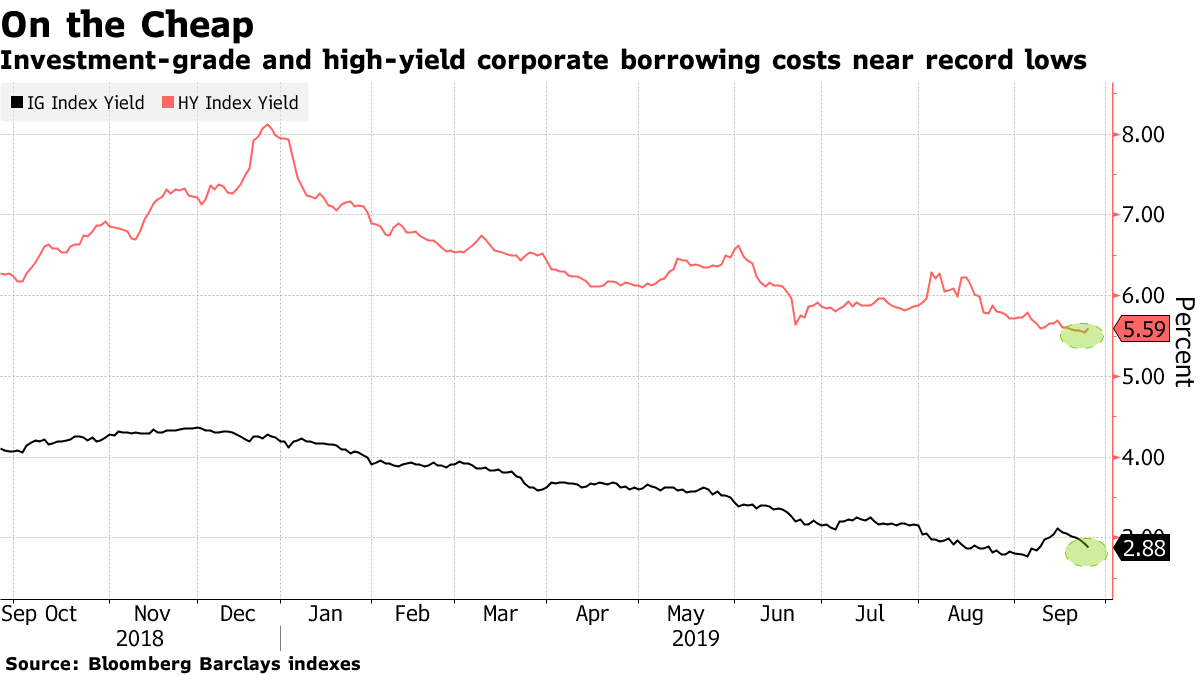

The change in heart comes as the Fed seeks to stoke growth by reducing borrowing costs, reacting to signals that the U.S. economic expansion is slowing. With long-term Treasury yields reaching a record low last month, investors may be betting that all that inexpensive debt financing will help those companies expand and drive future earnings growth.

“Money is a lot cheaper to borrow and close to free in some cases,” said Sylvia Jablonski, the head of capital markets at Direxion, which manages US$13 billion. “As long as that goes into the investment of the firm and helps the firm grow and increases capex in a positive way, then I think it could be something that’s positive for those firms.”

Take the performance of Edison International and Carmax Inc., for example, members of the S&P 500 Index with some of the highest ratios of net debt to earnings, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Both are up more than 30 per cent this year, trouncing the S&P 500’s 18 per cent return.

That’s not to say there’s hasn’t been a ton of hand wringing about soaring corporate debt levels and the fallout to come when things go south. Even the Fed’s rate cut, while helpful in the short term, runs the risk of merely delaying the reckoning that will surely arrive for overzealous borrowers.

Goldman Sachs pointed out that net leverage -- which measures how much companies owe for every dollar of earnings after subtracting cash on hand -- for the median company in the S&P 500 spiked to a record in the second quarter. JPMorgan also flagged growing debt levels this month as a risk, saying leverage metrics are worsening.

But rather than fret, equity investors are taking a chance on riskier firms. A Goldman Sachs basket of companies with weak balance sheets has bested a gauge of strong balance sheet firms for four straight months. Up 20 per cent year-to-date, the group of firms with more fragile finances is on track to beat the S&P 500 for the first time since 2016.

One reason for the faith? Extremely low borrowing costs. A divided Fed cut interest rates for the second time in two months on Sept. 18, reducing its federal funds target by a quarter percentage point to a range of 1.75 per cent to two per cent.

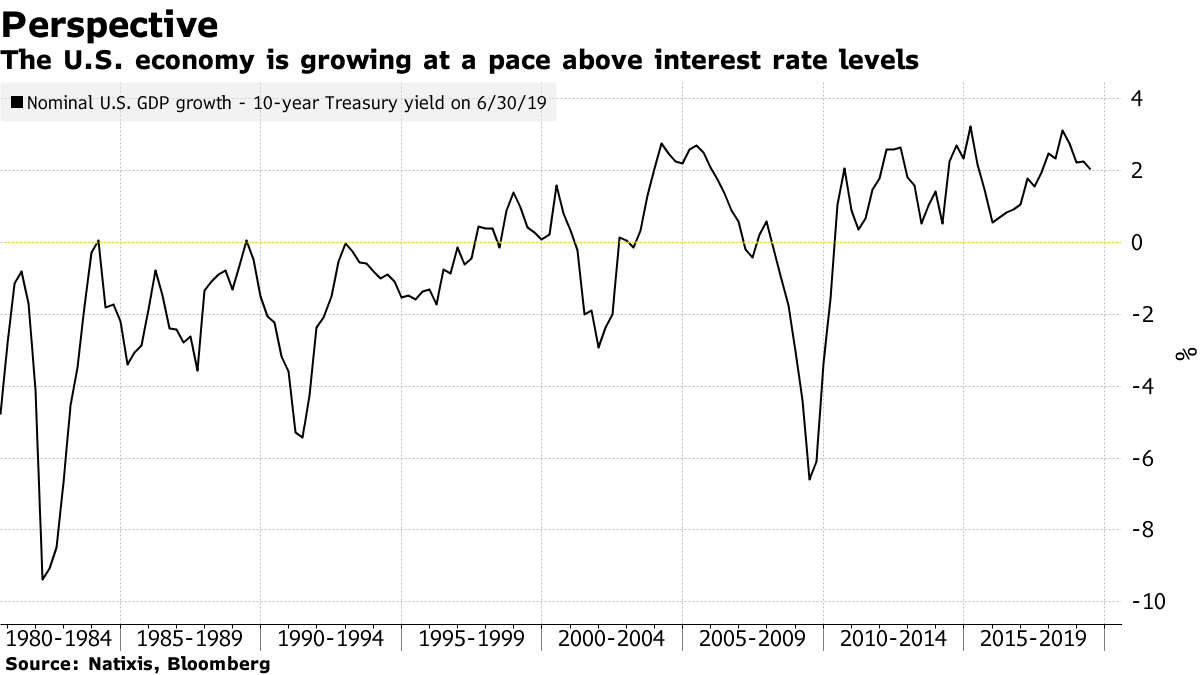

Interest rates in the U.S. aren’t high compared to the pace of economic growth, a dynamic that means companies should be able to easily meet debt payments, according to Joseph LaVorgna, the chief economist for the Americas at Natixis.

“If yields remain under nominal activity, a broad-based pickup in corporate defaults is unlikely,” he wrote to clients this month.

Companies have been on a refinancing tear in September, issuing bonds with lower interest rates and buying back more expensive securities. The U.S. investment grade market, with about US$155 billion priced this month, has already surpassed last September’s total, and more companies are looking to refinance with borrowing costs still low.

Of course bond investors are still being selective. In recent weeks, riskier companies have been forced to either offer higher interest rates or dangle sweeteners to drum up demand. At least four planned sales this month have been yanked from the market entirely.

The latest bout of strength in highly levered stocks may also be evidence of a trade gone too far instead of any particular love for finance chiefs who have borrowed a lot.

Earlier this year, valuations of firms with healthy finances versus those of their weaker peers had reached some of the highest levels since 1980, and Goldman Sachs said the phenomenon was due for a reversal amid more accommodative monetary policy.

And of course not all investors are keen on highly leveraged stocks. Sandy Pomeroy, manager of the Neuberger Berman Equity Income Fund, is sticking to companies with “squeaky clean” balance sheets. Whittier Trust, with US$13.5 billion of assets under management, has a bias toward high quality growth shares.

“Leverage is not a winning stock picking attribute,” Sandip Bhagat, Whittier Trust’s chief investment officer, said in an interview at Bloomberg’s New York headquarters. “The higher the leverage, the lousier the fundamentals, the lower quality the company is depicting. Don’t get tricked by it.”

But Barbara Reinhard, head of asset allocation for multi-asset strategies at Voya Investment Management, and Michael Kelly, global head of multi-asset at PineBridge Investment, both pointed to a thawing of trade tensions between the U.S. and China as supportive for highly indebted companies.

“A more predictable trade environment will lead to better business conditions, so you have some deeper pockets of credit and the stock market finding buyers,” said Kelly, whose firm manages US$97 billion. “It’s a little safer to wander out in the waters.”

--With assistance from Vildana Hajric.