Dec 6, 2022

Wall Street Managers Are Learning to Love Treasury Bonds Again

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Slowly but surely, bond haters are vanishing across Wall Street — even as fresh market havoc remains a distinct possibility next year if still-raging inflation forces the Federal Reserve to ramp up policy tightening anew.

Undeterred, money managers are starting to rebuild their exposures across the battered $24 trillion world of Treasuries, on the conviction that the highest payouts in over a decade will help cushion portfolios from the damage wrought by further interest-rate hikes.

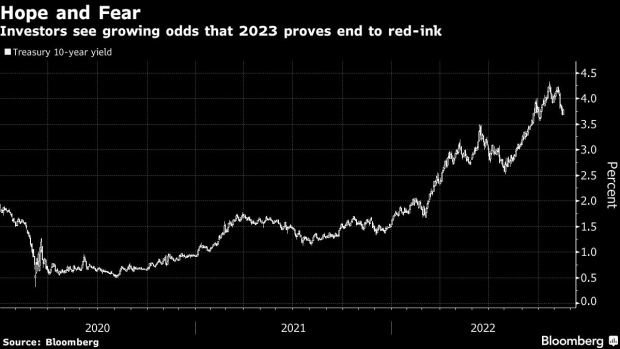

Morgan Stanley projects that a multi-asset income fund can now find some of the best investing opportunities in nearly two decades in dollar-denominated securities, including inflation-linked debt and high-grade corporate obligations. The interest payments on regular 10-year Treasuries, for example, has hit 4.125%, the highest since the global financial crisis.

Meanwhile Pacific Investment Management Co. reckons long-dated securities, the biggest losers in this era of Federal Reserve hawkishness, will bounce back as a recession ignites the bond-safety trade, with government debt acting as a reliable hedge in the 60/40 portfolio complex once more.

“People are excited, believe it or not,” said Maribel Larios, founder and CEO of Fiduciary Experts, a Murrieta, California-based registered investment advisor. “It’s all relative, as they’ve seen these fixed-income accounts pay little to nothing in the past. So, 4% — or even about 2% to 3% in some cash accounts — is relatively good now.”

Treasuries rallied again on Tuesday, pulling yields on the 30-year long bond back below 3.52%, a level last seen in September. The 10-year rate, meanwhile, has once again tested below 3.5% already and is now more than three quarters of a percentage point below its October peak, when it climbed above 4.3%.

Institutional managers who sell government debt to the investing masses are naturally predisposed to talk up the asset class, as is true of those peddling stocks and every other security. And many funds were blindsided this year by failing to anticipate how persistent inflation would become, which hammered the bond market with the steepest losses in decades as the Fed started raising rates aggressively.

But now thanks to beefy income streams and lower duration — a measure of interest-rate risk — it’s getting easier to make the case that bonds will prove their muster next year.

In Minneapolis, Minnesota, Bryce Doty, senior portfolio manager at Sit Investment Associates, is telling clients they can enjoy positive bond returns over the next 12 months. Doty is expecting Treasuries to eke out between 4% and 7%, a kind of bullish posture he hasn’t held for the past 18 months or so.

“Coupons are much higher and the two-year Treasury is providing 4.5% and we haven’t seen that in years,” he said.

It’s far from smooth sailing for Treasury managers, with liquidity conditions remaining troublesome, the inflation menace still at large and long-dated securities by no means cheap. On Monday, for example, yields jumped after a gauge of service-sector activity accelerated in November, confirming the economic strength seen in the jobs report Friday that showed faster-than-expected wage and payroll growth.

But it’s fair to say sentiment is improving for an asset class that has famously misfired for much of the post-lockdown era.

The median in the latest Bloomberg survey shows dealers, strategists and economists projected the 10-year US note would trade around 3.5% by end of next year. The yield on the policy-sensitive two-year obligation is seen falling to 3.63%, while the Fed’s policy rate ends 2023 at 4.5% to 4.75%.

Investing in bonds isn’t a slam-dunk trade clearly, with inflation likely to outpace the Fed’s 2% target through 2023. John Ryding, chief economic advisor at Brean Capital, expects the Fed will tighten rates to a higher-than-expected peak of 5.25% to 5.5% and then keep benchmark rates there through 2023.

A recession starting late 2023 into early 2024 is pretty inevitable, yet it’s the “persistence of inflation that the Fed will be ultimately concerned about,” said Ryding. “Even though evidence that inflation has peaked is encouraging, that and getting back down to the Fed’s target are two very different propositions.”

The bond market is already showing signs of getting ahead of the 2023 trade by driving 10-year yields below those on 2-year notes by the most since the early 1980s. On Tuesday, that so-called inversion — often seen as a harbinger of economic pain — hit a new extreme of 0.848 percentage points.

But going all-in on the recession trade by scooping up long-dated securities at this juncture may be premature and to some the securities look richly priced relative their short-maturity peers. Typically, long-dated yields tend to fall just before the Fed ends its tightening cycle and only when evidence of a recession is much stronger.

“Clients are leaning on the playbook from the post GFC with a 10-year seen heading back to 2.5% to 3%,” said Jason Bloom, head of fixed income, alternatives, and ETF strategies at Invesco, referring to the great financial crisis of 2008. “It’s a bit of hopeful thinking to get really bullish on the long end.”

To some, bonds away from the very short- and very long end of the maturity spectrum look like the hottest safety trade for 2023 as the Fed’s most aggressive tightening campaign in decades reaches a climax.

The three- to five-year area in bonds “looks pretty attractive once you think where the Fed likely ends — and history is not on the side of the Fed when it comes to keeping rates higher for longer,” said Jonathan Duensing, head of fixed income at Amundi US.

(Updates pricing.)

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.