Mar 17, 2020

Wall Street to governments: Think of a number then double it

, Bloomberg News

Mark Wiseman: Economy will recover rapidly if governments and businesses make right moves

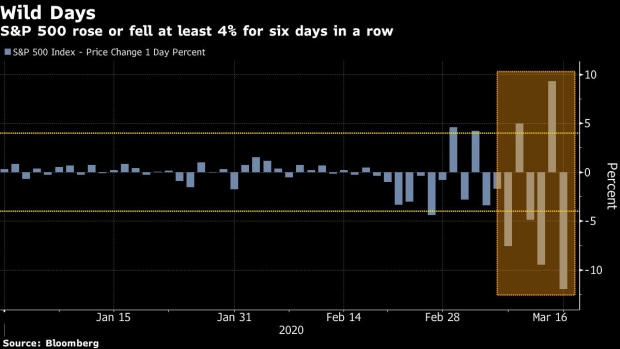

Think of a number, then double it. That’s more or less what Wall Street is telling governments racing to draw up emergency spending plans as the coronavirus brings their economies to a sudden stop.The near-unprecedented losses on stock markets, which persisted through a series of central-bank interventions, show that investors are looking to budget stimulus to put a floor under the slump, with government borrowing costs at historic lows.

But outside of China, no country has yet come close to delivering the kind of fiscal boost they typically deliver in a recession, according to JPMorgan analysts. Europe has rolled out a wide range of targeted steps which are hard to quantify, they wrote in a paper Monday, while U.S. easing “has been trivial so far.”

‘Nearly Zero’

Evidence for the scale of economic damage that the virus is about to inflict is mounting fast –- especially from China, where key economic indicators fell off a cliff at the start of this week.

With Western countries now in lockdown too, expectations that they’ll suffer a similar hit are mounting, and politicians in charge of the government purse strings are struggling to keep pace.In the U.S., for example, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said Tuesday that US$850 billion of measures are in the pipeline. The initial virus plan to arrive in Congress last week was worth about US$8 billion. Lawmakers are discussing sick-pay protections, but the shutdown across service industries in the last couple of days means millions of healthy workers risk losses too. And giant companies like Boeing Co. are joining the line for a government backstop.

The virus crisis “has brought forward a theme we have talked about for some time now – the end of monetary dominance and the beginning of more fiscal reliance,” said James McCormick, Global head of desk strategy at NatWest Markets.Small businesses “are the big risk here and will need support during a period of nearly zero activity,” he said “Households need paid sick leave. Airlines need funding support.”

‘Fiscal Thrust’

But if central banks aren’t well equipped to deliver those things, governments are having trouble deploying their own tools fast enough to satisfy markets -- whose swings this month have often hinged on whether they think fiscal relief is at hand.

John Normand, a strategist at JPMorgan, cited efforts by the bank’s economists to measure the “fiscal thrust” – the amount of economic growth that’s been spurred by budget policy. In the past two decades, downturns have typically been met with a thrust equal to between 1 per cent to 2 per cen of GDP, he wrote. At the moment, only Asian economies like China and Korea are coming anywhere near that.“Unless the U.S./Europe couple targeted measures with broad ones, the catalyst for market reversal may remain a peak in infection rates rather than a headline about game-changing stimulus,” he wrote.

‘Helicopter Drops’

Policy makers are stepping up attempts to patch together that kind of response. Germany publicly ditched its balanced-budget fetish and the French government said this week it will guarantee up to 300 billion euros (US$335 billion) of bank loans to companies in an effort to bolster virus-hit firms.

But after several days of market turmoil that recalled – and on some measures even exceeded – the last big crisis in 2008, many analysts think that policy makers will have to go significantly further. And they might have to break some new ground on the way.

“Governments may need to step in to directly guarantee liquidity provision to thousands of corporates and even individuals,” said George Saravelos, Deutsche Bank’s global head of currency research, “This may literally require helicopter drops of money.”