Nov 20, 2022

Wall Street Wants to Believe Xi’s Money-Minting Markets Are Back

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- More than two years of growth-squelching policies sent international investors fleeing China. It’s taken all of two weeks to lure them back.

From Morgan Stanley and Bank of America to TCW, Fidelity International and Franklin Templeton, some of the biggest players in global markets are turning increasingly bullish on Chinese assets. It’s a stark contrast from just last month, when foreign firms pulled an estimated $8.8 billion from the nation’s slumping stocks and bonds, and analysts were predicting more gloom ahead.

The dramatic about-face comes as Beijing seemingly shifts toward a more pro-growth footing, tweaking Covid policies to minimize economic and social costs, delivering a plan to rescue the beleaguered property market and dialing back tensions with the West. The result: mainland shares are up more than 7% in November, while the yuan is on pace for its first advance in nine months. With concerns that monetary-policy tightening in the US and Europe could soon tip the developed world into a recession, foreign firms are increasingly looking to China as a key portfolio hedge.

“Investors have to start thinking about what is going to be one of the big, global trades of 2023, which is going to be the China reopening trade,” David Loevinger, a sovereign analyst at TCW Group Inc. and former US Treasury Department senior coordinator for China affairs, said in a podcast last week. “The direction of China’s Covid policy is clear, tail risks are lower, and this is not going to be lockdowns forever.”

That’s not to say that international investors are ready to throw caution to the wind. Chinese stocks closed lower on Monday and the yuan weakened as the country’s first documented Covid deaths in almost six months sparked concern authorities could dial back the easing of restrictions.

Plenty of firms that have dialed back their China exposure in recent months have expressed little appetite to ramp it back up anytime soon. There’s unease over whether the country’s leadership is turning less pragmatic in guiding the world’s second-largest economy, pursuing increasingly ideological policies instead. And relations with the West remain fraught.

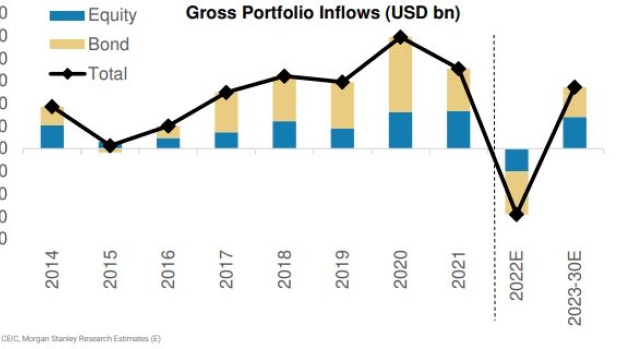

But amid the first annual foreign portfolio outflows in more than two decades and one of the nation’s biggest-ever stock-market routs, China’s leadership appears to be, if not acquiescing to the appeals of global investors, at minimum heeding their concerns.

“We’re starting to hear of emerging-market long-onlys looking to build up their onshore capacity,” said Winnie Wu, co-head of China equity research at Bank of America Corp. in Hong Kong. Her team recently turned bullish on Chinese stocks. “As long as the money-making effect is there, investors will return.”

Foreign capital has flocked to China for the better part of a decade as regulatory reforms opened the nation’s domestic markets to global money managers.

Overseas investors have accumulated 3.38 trillion yuan ($472 billion) worth of bonds in the onshore interbank market, according to official data as of October, while about 11% of mainland Chinese shares are held by foreigners, JPMorgan Chase & Co. estimates.

Yet international portfolio outflows across mainland stocks and bonds are on track to exceed an unprecedented $100 billion this year, according to Morgan Stanley, as President Xi Jinping has shown he’s willing to crack down on some of China’s largest companies and sacrifice growth in an effort to rein in debt, reduce income inequality and protect the country from Covid-19.

“It’s important to not sacrifice domestic interests for the sake of internationalization,” Guan Tao, chief economist at BOC Securities and an ex-official at the State Administration of Foreign Exchange, said in an interview. “In opening up its financial markets, China will follow the principle of initiative, gradual progress and control.”

China’s tolerance for economic pain in pursuit of Xi’s goals -- like Covid Zero or common prosperity -- helped fuel an almost 30% slump in the benchmark CSI 300 Index this year through the end of October. The Hang Seng China Enterprises gauge of mainland companies listed in Hong Kong was down 40%.

“If you’re an international investor, trying to second guess what the authorities are doing is more difficult in an environment where they’re not purely prioritizing economic growth,” Vivek Paul, a senior portfolio strategist at BlackRock Investment Institute, said in a Bloomberg TV interview last week. “What we’ve seen recently are necessary -- but not necessarily sufficient -- conditions for a strong rebound.”

‘Huge Opportunity’

Still, Chinese asset prices are so beaten down that many Wall Street firms say the balance of risk has become decidedly skewed to the upside.

Morgan Stanley recently boosted its forecast for the country’s stock gauges, predicting the MSCI China Index will rally 14% by the end of next year, while Bank of America turned tactically constructive on the country’s shares. Citigroup Inc. upgraded Hong Kong equities to overweight, and said recent policy changes will lift earnings.

“We all knew that China couldn’t just be isolated forever,” Catherine Yeung, an investment director at Fidelity International Ltd., said last week in a Bloomberg TV interview. “So much negative news flow has been now factored into the price. It just feels like China is likely to have seen its worst.”

While Beijing is unlikely to pursue a hard decoupling, it’s becoming more wary about the potential risks of foreign investment, according to Victor Gao, chair professor at Soochow University and vice president of think tank Center for China and Globalization. The concern is that greater reliance on overseas funding could leave China vulnerable to harsh restrictions imposed by the West.

“There’s a lot of wariness about what the US is up to now,” said Gao, who worked as an interpreter for former leader Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s. “That’s why China is building a wall.”

Still, the country is likely to continue courting foreign capital in the years ahead.

A narrowing current account will make China “hungrier for global capital” toward the end of the decade, according to Morgan Stanley, requiring at least $150 billion of foreign inflows annually to plug the financing hole.

“We’d like to see the Chinese government being more willing to accept foreign investment and let the markets operate,” Raphael Arndt, chief executive officer of the Future Fund --Australia’s sovereign wealth fund -- told Bloomberg TV at the Bloomberg New Economy Forum in Singapore last week. “We think there’s a huge opportunity still.”

--With assistance from Qizi Sun and Ye Xie.

(Updates prices in third and fifth paragraphs. Adds Citigroup report in 16th paragraph)

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.