Apr 15, 2019

Warren Has a Good Beginning for Ending Corporate-Tax Avoidance

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Each year, publicly traded corporations prepare two sets of books. The first is a basic quarterly profit and loss statement that is widely disseminated to shareholders, analysts and the media.

The second is the firm’s annual corporate tax filing, submitted to Uncle Sam. It includes a statement of the year’s profits, on which tax obligations are owed to the government -- if any.

The differences between these two reports can be very different. For companies such as Apple Inc. and Amazon.com Inc., these two numbers can vary by tens of billions of dollars.

It isn't that either of these numbers are false; but rather, they are more like opinions prepared using very different standards. Quarterly earnings use generally accepted accounting principles. These accounting rules have been adopted by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) as acceptable legal guidelines for reporting earnings. For corporate taxes, the rulebook is the Internal Revenue Service guidelines, which look nothing like GAAP. For example, depreciation expenses are part of corporate overhead -- affecting profits like any other spending would -- but its impact can dramatically reduce what is owed in taxes. Similar issues arise with other aspects of corporate profitability, such as stock options, fringe benefits and debt servicing.

The gap between reported profits and taxes owed appears to have grown even larger, in part due to the Trump tax cuts of 2017. One of the modifications that affected the gap was the repeal of the corporate alternative minimum tax.(1)

This isn't the sort of wonky issue that usually attracts much attention. But in this case it is prime fodder for political and policy gaming. Along with the tax cut, a few other things are stirring the debate. These include:

• The declining corporate share of total federal tax revenue;

• Growing wealth and income inequality;

• Discussions on reforming capitalism from Ray Dalio, Jamie Dimon and others;

• The 2020 presidential election

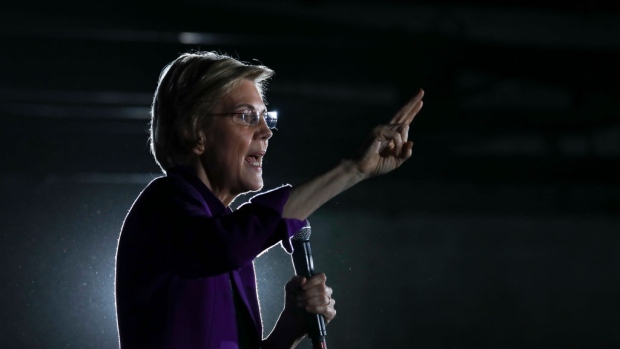

Into this fray steps Democratic Massachusetts Senator and presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren. She has a somewhat novel proposal that she says would resolve the difference between these two sets of numbers while promoting a fairer split of the federal tax burden between individuals and corporations.

She calls her proposal the “real corporate profits tax,” and she claims it could generate as much as $1 trillion in tax revenue during the next decade. Among the features is a 7 percent surcharge on corporations that report more than $100 million in annual net income to shareholders. What makes her proposal so intriguing is that it would reconcile the difference between reported profits to shareholders and reported income to the IRS.

As examples, Warren points out that Amazon had net income of more than $10 billion in 2018 and paid no federal income tax. Same for Occidental Petroleum Corp. with 2018 net income of $4.1 billion.

To be sure, many companies do not generate much in the way of profits, either by circumstance or design. Newer businesses such as the now-public Lyft Inc. and soon-to-be-public Uber Technologies Inc. have been losing money for years. Older tech companies like Twitter Inc., Snap Inc., Box Inc. and Square are also not especially profitable. Ever since his very first letter to shareholders in 1998, Amazon founder and chief executive officer Jeff Bezos has been consistent in saying that profitability was always going to take a backseat to reinvesting in the company and pursuing market share.

But those unprofitable companies are not the target of Warren’s ire -- she is instead aiming at the biggest companies that have successfully avoided paying taxes via overseas accounting maneuvers. The senator estimates her proposal would apply to about 1,200 of the most profitable businesses in the U.S. The first $100 million in profits would be exempt; the 7 percent tax would apply to all profits over that.

What is a bit surprising is that Warren singled out Amazon but not Apple, which is the poster child for U.S. corporate-tax avoidance. A substantial portion of its $245 billion cash hoard can be attributed in large part to its success in skirting taxes despite its immense profitability. In 2018, Apple’s net income was $59.4 billion; under Warren’s proposal, Apple would have owed about $4.15 billion in additional taxes.

Warren's plan is clever in a number of subtle ways. The first is that it will operate as an alternative minimum tax for the biggest most profitable companies, such as Apple, Amazon and plenty of others. The second is it implicitly acknowledges antitrust and monopoly concerns raised by critics like Scott Galloway of the largest and most successful corporations.

The odds of Warren's plan being adopted are surely rather long. But one thing is for sure: This is a subject worthy of more debate as the presidential elections heat up later this year.]

(1) According to the Tax Policy Center: “Originally intended to prevent perceived abuses by a handful of the very rich, the AMT affected roughly 5 million filers in 2017. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act dramatically reduced the reach of the AMT, albeit temporarily, so that the tax will hit only 200,000 filers in 2018.”

To contact the author of this story: Barry Ritholtz at britholtz3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Barry Ritholtz is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He founded Ritholtz Wealth Management and was chief executive and director of equity research at FusionIQ, a quantitative research firm. He is the author of “Bailout Nation.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.