Oct 1, 2020

We're a Long, Long Way From Running Out of Gold

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Here’s one potential reason to add some bullion coins or bars to your investment portfolio: They’re not making any more of them.

All the gold that’s ever been mined would fit into a cube with edges 22 meters long — small enough to fit into three Olympic-sized swimming pools. Each year, miners and pawnbrokers add another 4,000 to 5,000 metric tons to an existing 197,576 ton pile, but jewelry demand alone uses up about half of that.

With the metal hitting a record $2,075 a troy ounce in August, the concern we’re heading toward peak gold has reared its head again. The industry needs to commission 8 million ounces of projects by 2025 to maintain last year’s production levels, consultants Wood Mackenzie wrote in June, requiring some $37 billion of capital investment. Mine production fell last year for the first time in more than a decade. Even the British Broadcasting Corp. has been asking whether we’re at risk of running out.

At the core of the concern is a longstanding trend in the gold mining industry: The percentage of gold in ore reserves is falling, from more than 10 grams per ton in the late 1960s to barely more than 1 gram per ton nowadays. Those concentrations are extraordinarily low — equivalent to grinding up and separating a Statue of Liberty’s-worth of ore to recover a teaspoon of precious metal. At some point, the grade must get so poor that it becomes impossible to recover the gold economically.

The thing is, we don’t know when that will be — and all the evidence indicates that we’re still a long way from finding out.

Take Newcrest Mining Ltd.’s Cadia East mine 200 kilometers (124 miles) to the west of Sydney. The grade there is just 0.45 grams per ton — more than two Statue of Liberty’s-worth per teaspoon — and yet the mine is one of the world’s most profitable, with costs of $160 per ounce, which would deliver a margin of more than 90% at current gold prices(2).

Two factors drive that. One is economies of scale: Cadia is one of the world’s top 10 gold mines measured by output. Since the dawn of the mining industry, grades of almost every mineral have been falling because, by definition, the highest-grade, most easily discovered resources are the ones that get exploited first. The growth of the sector has always depended upon better, higher-volume extraction technologies offsetting this fact.

The place where many of the highest-grade major gold deposits are still found, South Africa, is increasingly a backwater. That’s because it’s simply so difficult to extract ore from sweltering tunnels kilometers underground using hand-operated tools. By comparison, the immense blasting and dump-truck operations used to exploit lower-grade mines in Siberia, Oceania and Nevada are far more efficient.

The other factor is that most gold doesn’t occur on its own. Indeed, the best deposits globally are porphyry, a mineral that’s also one of the world’s biggest sources of copper. The operator of the world’s biggest gold mine isn’t a gold miner at all but copper producer Freeport-McMoRan Inc., whose Grasberg pit on the Indonesian side of New Guinea produced nearly twice as much gold in 2018 as its nearest rival, Polyus PJSC’s Olimpiada. At Newcrest’s Cadia, production costs are so low because for every ounce of gold that’s mined you get about 140 kilograms (309 pounds) of copper, worth $900 or so at current prices.

While the issues of mine depletion highlighted by Wood Mackenzie are real, high gold prices like those we’re seeing at the moment are exactly the circumstances that will encourage more exploration and development activity to make up the shortfall. Though people have been digging up gold for seven millennia, it’s constantly being discovered in the most unexpected places.

Mining of the yellow metal in Australia’s Victoria state all but ceased a century ago after the veins that drove its nation-building 19th-century gold rush were tapped out. Then in 2015 Kirkland Lake Gold Ltd. discovered a new ore body near its uninspiring Fosterville mine site, and realized it was sitting on top of one of the world’s highest-grade deposits, causing its market capitalization to grow nearly 100-fold in five years.

The same year, a unit of Zhaojin Mining Industry Co. discovered a new deposit two kilometers below the surface of the Bohai Sea off the coast of northeast China’s Shandong province. With some 212 metric tons of proven and probable reserves, it’s now one of the world’s largest gold deposits.

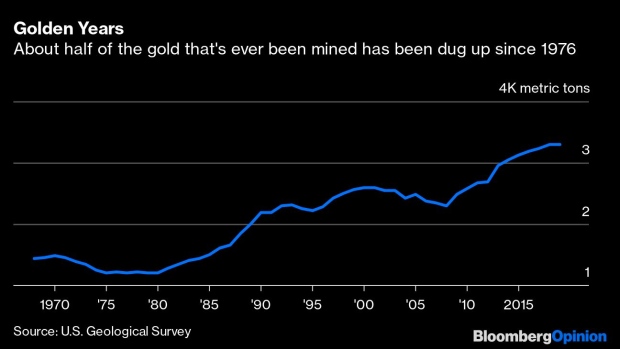

There’s no reason to think that trend is about to break. About half of the world’s gold has been mined since 1976, and if anything the pace is accelerating as grades fall. Worldwide, gold production is up by about a third over the past decade, far more than the 15% increase in oil output. The best reason for investing in gold is still that it provides diversification to an investment portfolio — not that the world doesn’t have enough of it. One day, we may run out of gold. We’re a long, long way from that moment now.

(1) The costs are for both Cadia East and the adjacent Ridgeway mine combined -- but Ridgeway is similarly low-grade, at 0.54 grams per ton.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.