Nov 8, 2022

What Happens After Warming Hits 1.5C? A Guide to Climate Overshoot

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The diplomats and world leaders now gathered in Egypt for the annual United Nations climate summit are tasked, in some sense, with holding the global average temperature below 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming. That’s one of the key objectives around which the 2015 Paris Agreement was formed, and so it has become a shorthand for the success of every subsequent climate summit.

Talks in Glasgow last year at COP26 ended with the conference leader saying the limit of 1.5C is “alive but its pulse is weak.” Ahead of COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh, UN-backed scientists on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change contributed to the darkening prognosis by projecting that the world is likely to pass the 1.5C mark in the 2030s. Obituaries for 1.5C have followed, even if politicians speaking from the ongoing summit in Egypt haven’t quite given it up for dead.

“If we retain the spirit of creative optimism — Promethean, creative optimism that we saw at Glasgow — then I think we can keep alive the hope of restricting the rise in temperatures to 1.5,” said former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson on Monday. He went on to repeat a slogan invoked often when he hosted COP26: “Keep 1.5 alive.”

Every tenth of a degree matters, which is why countries codified in the Paris Agreement their plan for “holding the increases in the global average temperature to well below 2C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5C.” In other words, there’s no precipice or event horizon on the other side of the line. It’s an organizing principle.

“The thing that’s obviously really important to say is that the 1.5C limit is a political limit,” says David Keith, a Harvard University physicist and an adviser to the Climate Overshoot Commission, an expert group that suggests ways to reduce risk once the world exceeds these warming targets. “Whether it matters or not depends on how it matters politically. It’s not like there’s some scientific magic at 1.5C.”

The emergence of the 1.5C goal in the global political consensus remains nothing short of remarkable. Small-island nations and other developing countries first pushed for official consideration in the UN agenda in 2009, after years of rich-world diplomats and researchers suggesting 2C as the best approximation of the climate danger zone.

Prompted by the Paris Agreement, scientists in 2018 published a major report finding that an additional half-degree Celsius of warming considerably upped the odds of harsher climate impacts. That report — specifically a sentence in it that can arguably be considered among the most influential ever written — kicked off a fast and intense global race among countries, cities and companies to claim they’re on a trajectory to zero-out the effect of their emissions by mid-century.

Progress toward a global clean-energy transition and general decarbonization is proceeding at a rate only dreamed of a decade ago. Falling costs for solar and wind energy, batteries and electric vehicles continue to push into the economy. Technologies and nature-based approaches that remove carbon dioxide directly from air are proven but remain expensive.

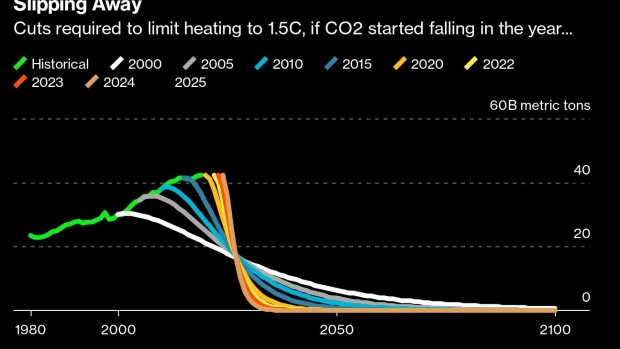

The most authoritative statements on how these efforts are doing come from the IPCC. A report in April, authored by hundreds of researchers and based on 18,000 studies, found that the amount of time left is small and shrinking. Emissions must peak before 2025, the IPCC wrote, meaning there are roughly 80 months left to have a 67% chance of staying under 1.5C. (To keep the 2C target, by contrast, there remains 24 years of CO₂ emissions left.)

Emissions, of course, are still rising. Few of the probable futures from here are compatible with stopping before the 1.5C limit is breached. Of 230 scenarios in the latest IPCC report that keep temperatures at or below 1.5 by 2100, 96% pass by that threshold in the near term before nascent carbon dioxide removal technologies kick in and warming eventually drops back down. That means we can still create a 1.5C compatible world, even if we break through that limit initially.

Interest in CO₂ removal is growing rapidly, and scientists have come to recognize it as a necessary method for reducing emissions from hard-to-change sectors such as aviation. Pulling down enough CO₂ to cool the planet by a tenth of a degree Celsius would cost $22 trillion, if the price per ton of removed carbon can reach $100.

That’s “ambitious from where we are today,” says Zeke Hausfather, climate research lead at the payments company Stripe and a contributor to international and US climate assessments. Bill Gates has said he spends closer to $600 per ton to purchase carbon removals using direct-air capture.

In an overshoot scenario in which the global average temperature goes beyond 1.5C and humanity deploys costly technologies at scale to complement emissions reductions, the distance traveled over that line will become crucial. The UN Environment Program publishes an annual report showing how far actual emissions and trends remain from agreed-to limits. This year's Emissions Gap Report concludes that existing policies would bring an estimated 2.8C temperature rise. All of the Paris Agreement pledges made by nations, if fulfilled, would lead to an average estimate of 2.6C warming, according to Inger Andersen, UNEP executive director.

A best-case scenario would see nations fully implementing their UN pledges, net-zero goals and additional policies. That situation would “point to a 1.8C rise,” she writes in the forward to this year’s UNEP report. “However, this scenario is currently not credible.”

The further warming goes up before emissions peak, the more radical the approaches that may become necessary. One strategy among these last-resort tools is geoengineering, or temporarily cooling the planet by seeding the upper atmosphere with reflective chemicals or similarly drastic interventions. “Between 10% and 1% is where I put the odds” of staying below 1.5C, says Harvard’s Keith. “Maybe closer to 1%.” For years he has pushed colleagues and policymakers to research geoengineering as an option, holding it out as a temporary measure to cool the planet from above while countries complete the fossil-fuel exit on the ground.

Wim Carton, a sustainability scientist at Lund University in Sweden, is writing a book about the idea of overshoot (alongside his colleague Andreas Malm). This research has made him wary of relying on a cocktail of geoengineering and carbon removal. There’s a danger that overconfidence in coming back from an overshoot will blunt the most proven way to combat rising temperatures: ending emissions as soon as possible.

“It seems kind of far-fetched to think that we somehow return to that temperature,” Carton says. It’s more likely that “we’ll instead somehow shift our baseline and start living with these massive impacts,” he says. “I see a future in which the Global North is able to adapt or construe its way out of significantly more than 1.5C without having to step up its ambition.” Such an outcome would leave billions of people in developing countries extremely vulnerable.

Climate scientists are quick to point out that the 1.5C or 2C limits were not chosen by the Earth system itself. So maybe the answer to “Is the 1.5C limit dead?” is simply that it’s the wrong question. There are many, better alternative questions: “How much lower than last year will your personal emissions be?” “What’s the impact of voting in elections on climate progress?”

The world has already breached 1.2C of warming. Given the extraordinarily unfavorable odds staying on the near side of 1.5C, after years of rallying around this number, does it still makes sense as a goal? Extremely difficult is not the same as impossible, and progress requires targets. “I think it has had mobilizing potential,” Carton says, “and therefore I'm kind of reluctant to give it up.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.