Feb 23, 2022

What's at stake for global economy as Russia standoff escalates

, Bloomberg News

Biden will tap into SPR if Russia invades Ukraine: RBC's Helima Croft

A world economy that’s still recovering from COVID-19 faces new risks from an energy-price spike as the standoff between the West and Russia escalates.

The U.S. and its European allies unveiled limited sanctions on Tuesday, in response to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s decision to recognize two breakaway republics in eastern Ukraine, and warned that tougher penalties may follow. Russia, whose troops are massed around Ukraine, says it has no plans for a full-scale invasion.

The crisis has driven oil prices toward US$100 a barrel and sent tremors through other commodity markets too, threatening another wave of price pressures on top of already-high pandemic inflation. Russia is a commodities powerhouse and a key supplier of energy to Europe.

Western nations are caught between the desire for harsh sanctions to deter Putin, and concern that they’ll suffer blowback themselves. For now, Europe and the U.S. have shied away from blocking Russia’s energy exports, or freezing it out of dollar-based finance. Even so, U.S. President Joe Biden warned Americans Tuesday that there’ll be a price to pay at gasoline pumps back home.

Below is a breakdown of how an escalating crisis over Ukraine could hurt the world economy, and who stands to lose most.

EUROPE EXPOSED

While there’s been no physical disruption to commodity flows, fears of an escalation have sent prices of everything from oil and gas to wheat, fertilizer and industrial metals soaring in recent weeks.

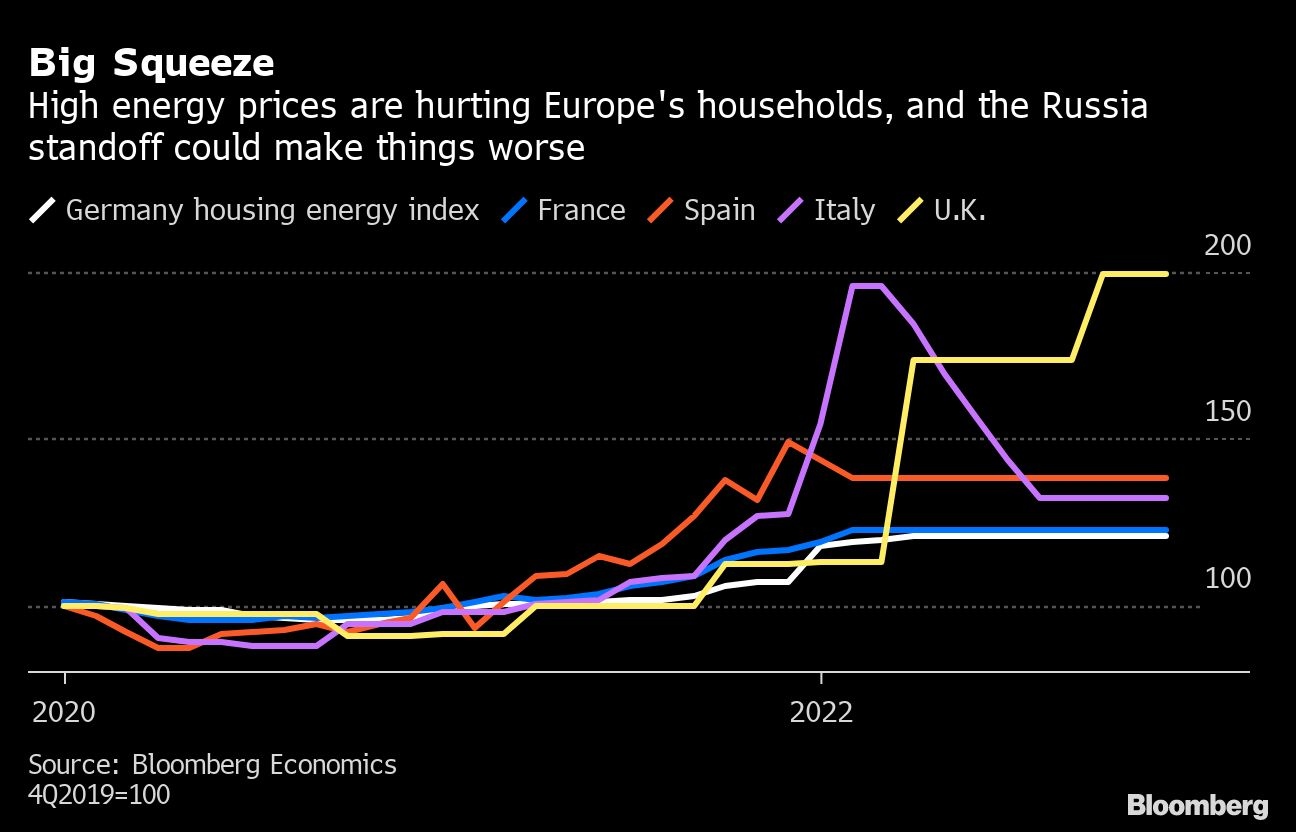

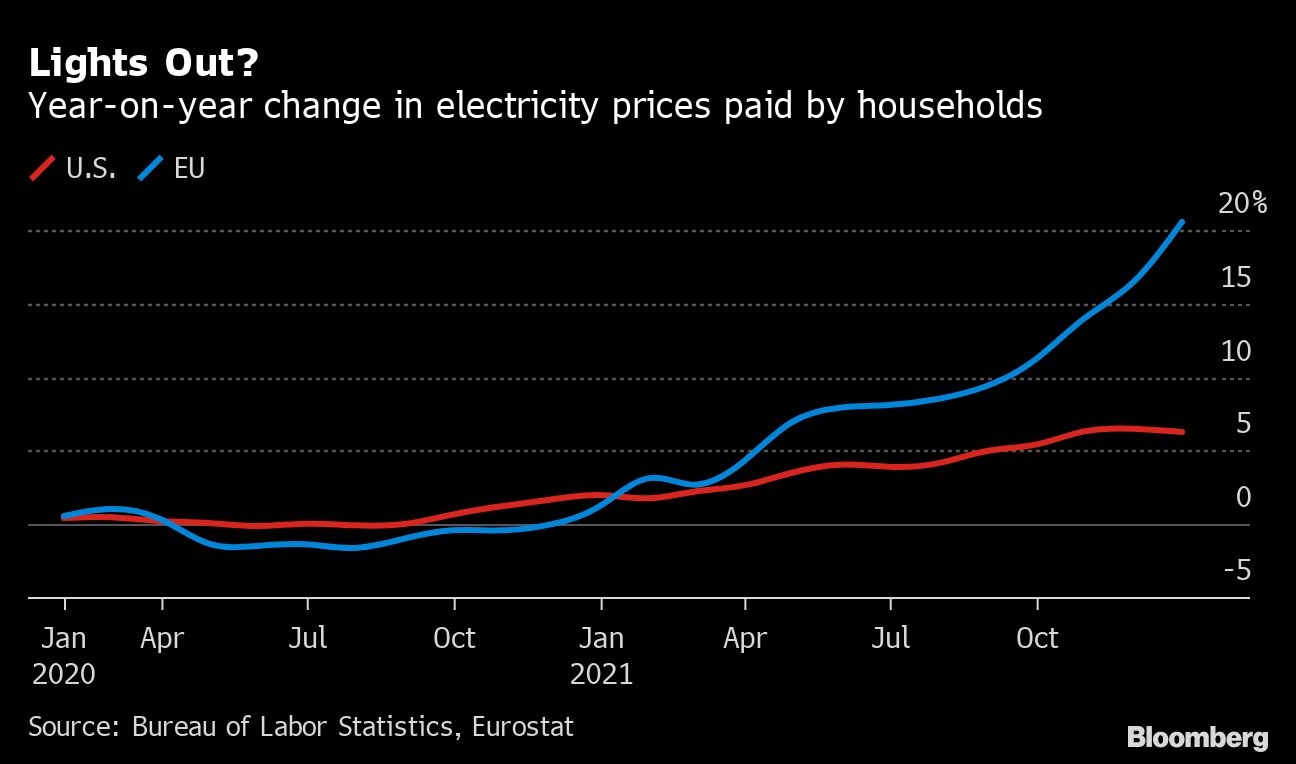

In Europe, which gets more than half its oil and gas from Russia, households are already paying higher bills for power and heating. Energy costs accounted for more than half the Euro area’s record inflation rate in January. Uncertainty about future Russian supplies could make the squeeze even worse.

Officials at the European Central Bank say that persistently high energy prices could slow the economy’s recovery by leaving households with less cash to spend on other stuff, and eating into corporate profit margins. JPMorgan economists cut their first-quarter growth forecast for the Euro area from 1.5 per cent to 1 per cent, though they still expect its economy to be back on its pre-pandemic growth path by year-end.

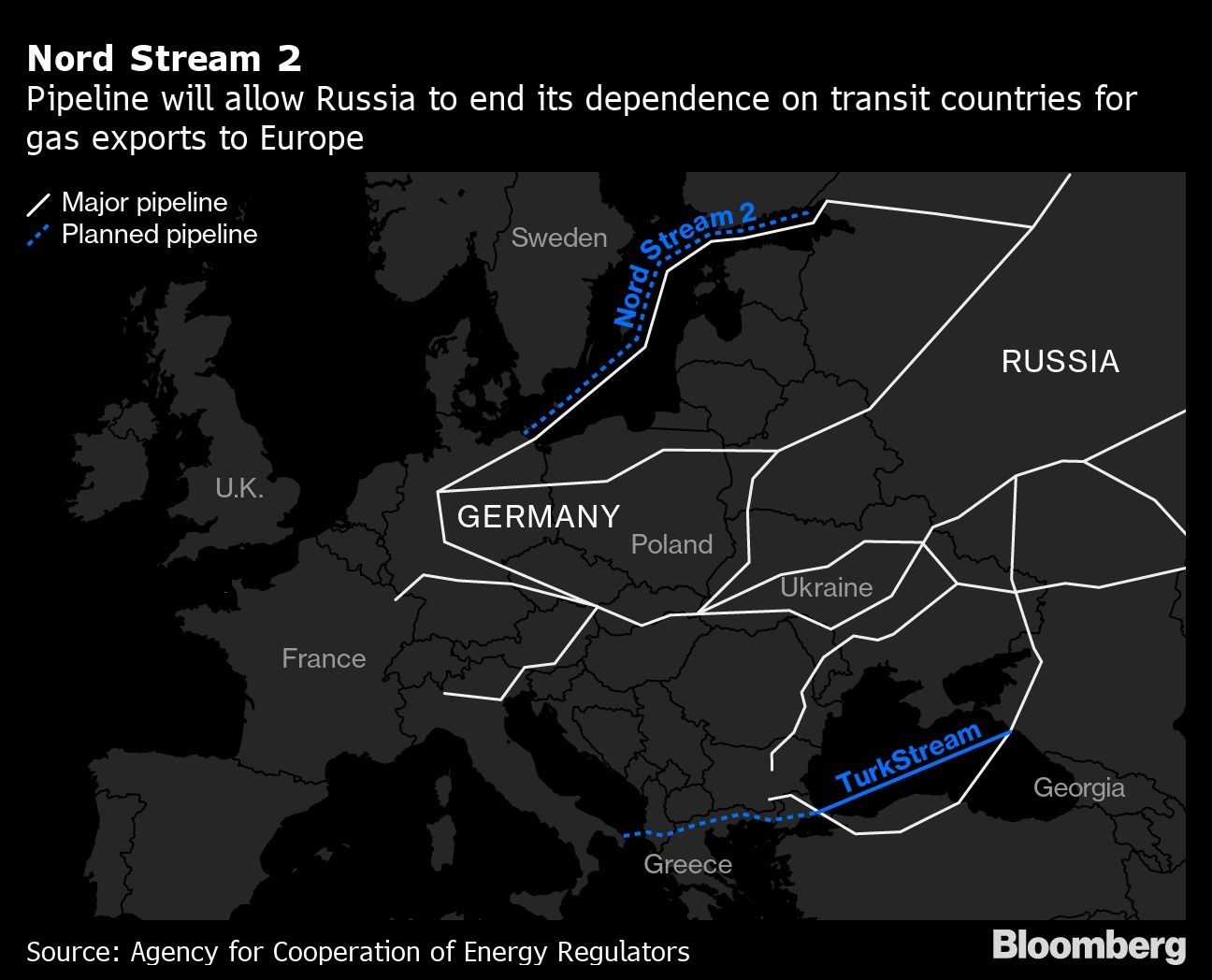

Germany, which plans to retire all of its nuclear power plants by the end of this year, is especially dependent on gas imports, one reason why it invested in the US$11 billion Nord Stream 2 pipeline to double supplies from Russia. The project was completed last year and awaiting approval from regulators, but it’s now been suspended as part of the measures against Russia.

FOOD SECURITY

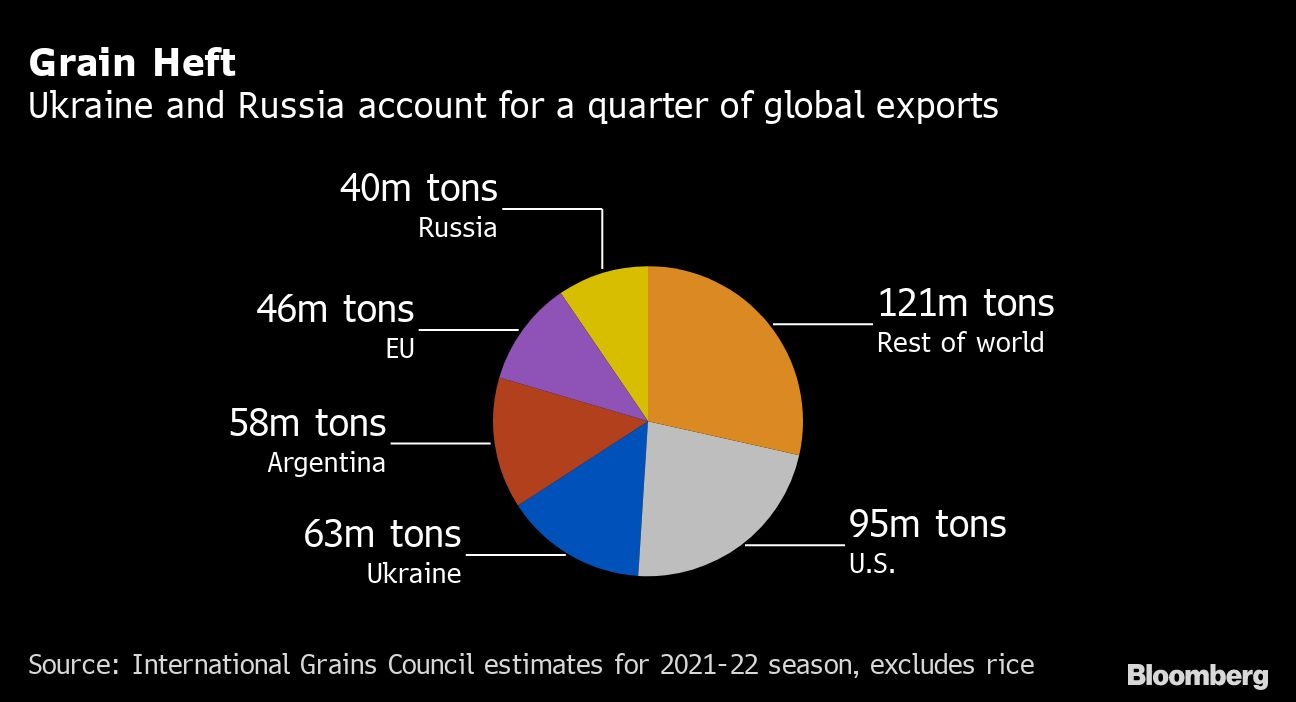

Both Russia and Ukraine are major producers of wheat, and prices have risen as traders fret about the possibility of disruption to shipments via the Black Sea. That’s especially worrying for countries in North Africa, where volatility in the cost of bread has in the past triggered unrest and toppled governments.

Developing economies, where food and energy weigh more heavily in household budgets, have already been slower to recover from the pandemic than their rich-world peers. They’ve also had to raise interest rates faster, to rein in inflation and prevent capital flight. A major escalation in the Ukraine standoff, which drives energy and food prices up, could “require another round of hikes,” said Elina Ribakova, deputy chief economist at the International Institute of Finance in Washington.

Metals are another area of risk. Military conflict or more punitive sanctions could disrupt Russian exports of palladium -- used to make the catalytic converters that lower car emissions -- or aluminum and steel, according to a recent report by Rabobank. The strategic importance of such materials could make them less likely to be targeted by Western sanctions.

BIDEN VOTE RISK

The U.S., unlike Europe, is a major producer and exporter of energy so its economy is less exposed. Still, there are political risks for Biden -- whose Democrats must defend slim Congress majorities in elections this year -- from higher pump prices. In his address on Tuesday, Biden said the U.S. is working with other countries to mitigate any impact, without giving details.

Peter Harrell, an official on the National Security Council, told Bloomberg Television that the measures against Russia shouldn’t hurt U.S. supply chains too much. “We have done a very deliberate mapping exercise over the last couple of months to understand where we have dependencies on Russia, and worked with companies to diversify them,” he said.

Officials at the Federal Reserve, who are preparing to start raising interest rates to counter inflation, have warned that geopolitical turmoil could lead to higher prices.

GLOBAL RESILIENCE

Still, most economists expect any price spikes from the Ukraine standoff to prove short-lived, meaning they won’t feed into wage expectations and drive long-lasting inflation. That would allow central banks to stick to their current plans, which involve tightening monetary policy by enough to dampen price pressures but not by so much as to derail post-COVID recoveries.

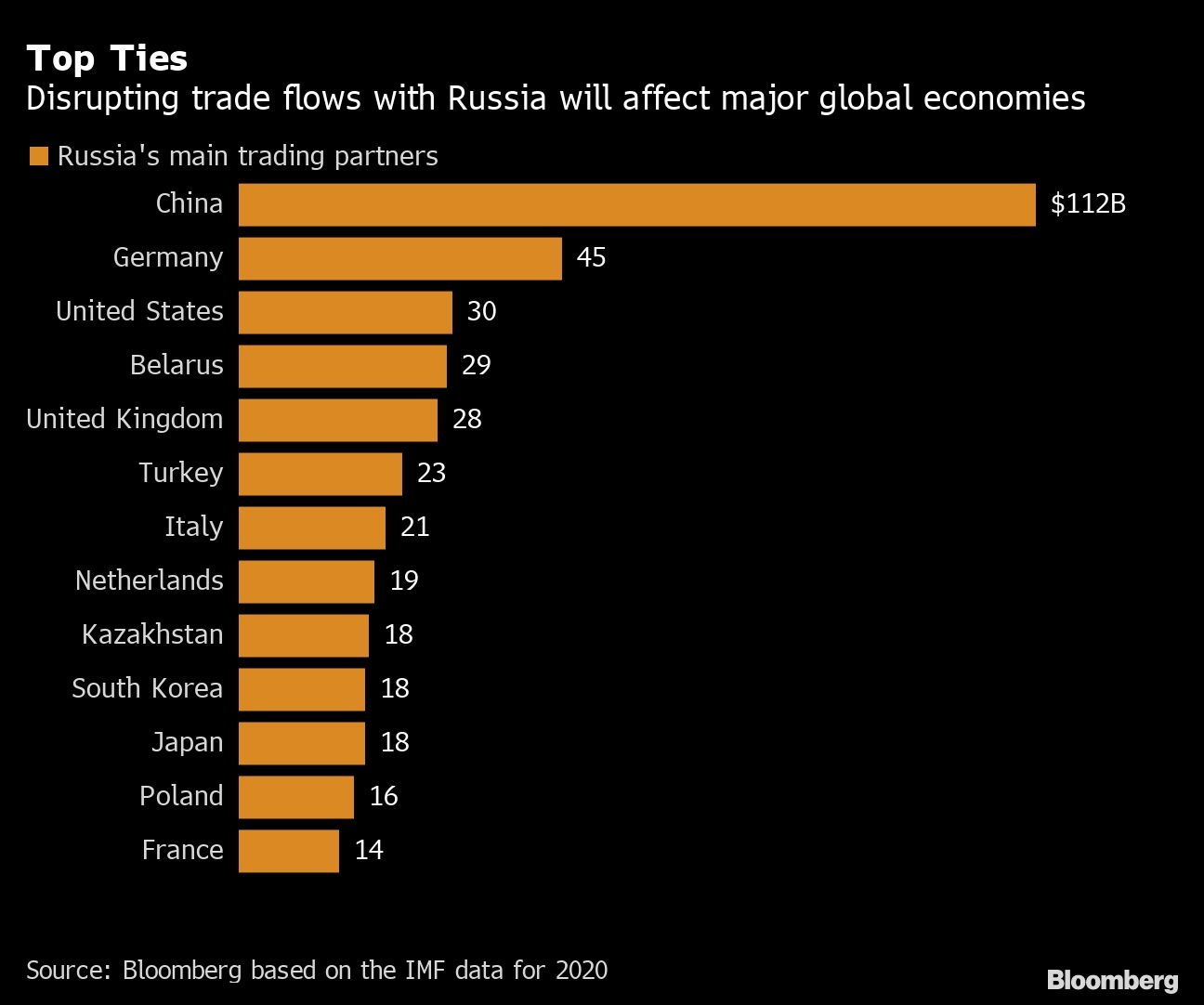

Even for Europe, the pain will likely be tolerable. While Germany is Russia’s second-biggest trade partner, those links account for a small percentage of its overall trade -- and many European companies already reduced their exposure to Russia after it was sanctioned for annexing Crimea in 2014.

“Market concerns about the most extreme scenario are probably overdone,” said Paul Donovan, London-based global chief economist at UBS. “Markets forget that people adapt to crisis and find efficiencies. In Europe, we could see campaigns for people to turn down thermostats or work from home. It wouldn’t stop the economy.”

FORTRESS RUSSIA?

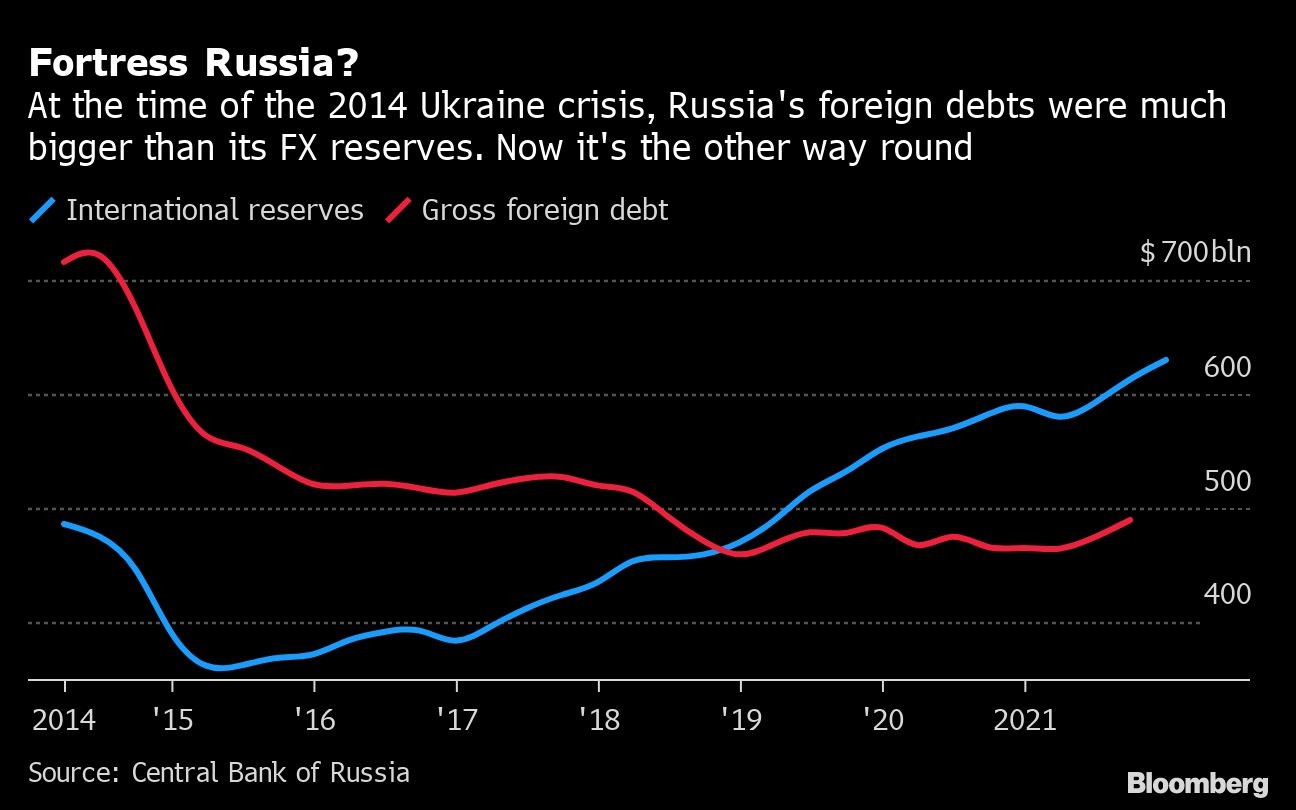

The Crimea sanctions sent Russia into recession and its financial system into crisis.

Since then, the government has been working hard to sanction-proof the economy. It has encouraged domestic production, reduced external debt, and built up reserves of foreign currency that can now be bolstered even further thanks to soaring energy prices.

Absent a major military conflict, Russia’s economy is likely to keep expanding, though Capital Economics forecasts that growth could drop below 1 per cent. In the longer run, U.S. and European sanctions would likely hold back the economy’s potential.

CHINA A WINNER?

Even without an escalation in the fighting or a harsher round of sanctions, Russia could turn east for economic relief as its ties with the West sour. China is already Russia’s biggest trade partner, and the countries have discussed building new pipelines to carry Russian gas.

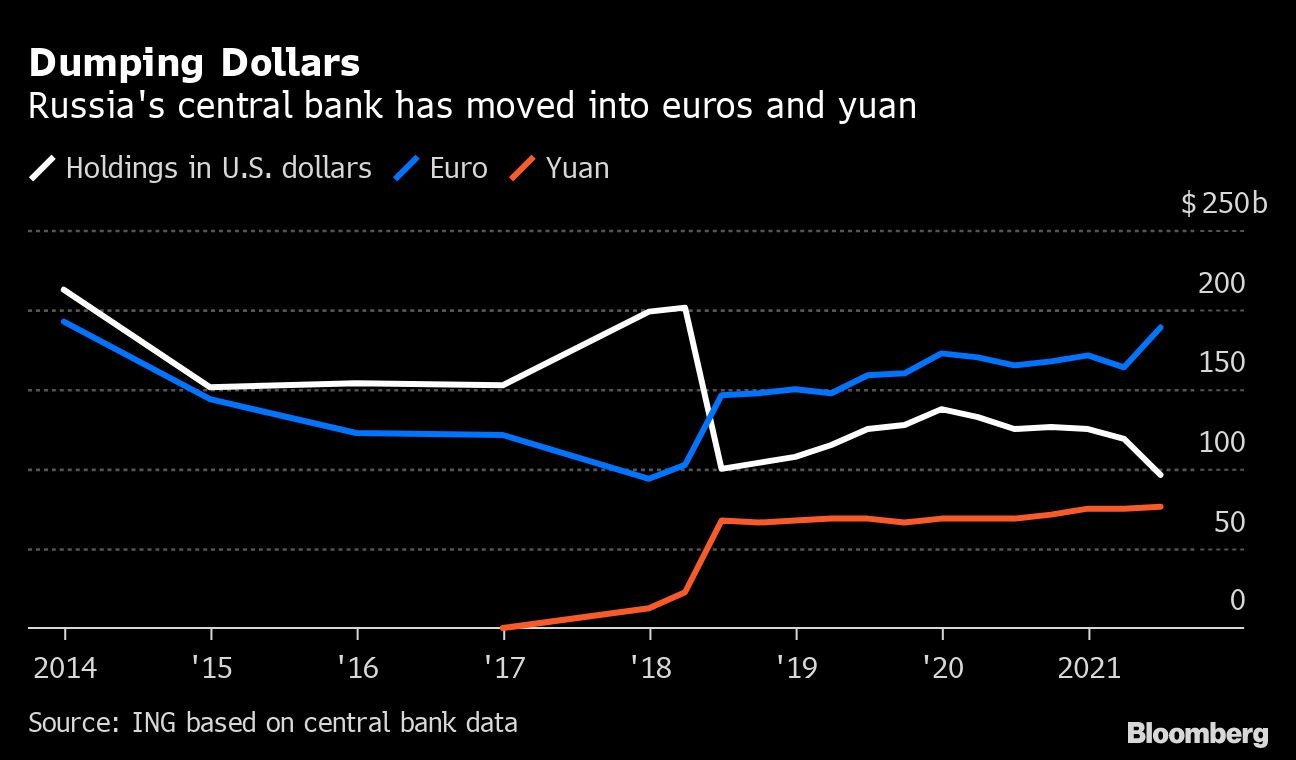

Russia has also been working with China to build new systems for international payments that can bypass the dollar and thus reduce U.S. ability to apply pressure via sanctions, as well as cutting its own holdings of the greenback.

WARS ARE UNPREDICTABLE

Geopolitical standoffs and military conflicts are inherently hard to forecast. The tensions between Russia and the West could evolve in ways that don’t appear likely now, such as a large-scale exodus of refugees from Ukraine to Western Europe.

“Wars evolve in unpredictable ways,” David Kelly, the chief global strategist at JPMorgan Asset Management, wrote in a recent note. “No one should assume that they can see all the impacts of a war at its outset.”