Sep 12, 2019

What Will Fill the Gap?

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Gap Inc. offered a first glimpse Thursday of how it aims to proceed once it splits its retail empire in two. The upshot: Do not expect a return to glory at its namesake chain any time soon.

After Old Navy becomes a standalone business, the new company, which will include the Gap, Banana Republic, Athleta and smaller brands, will face a difficult set of challenges. Some of these are the result of the bleak retail landscape — but several are of its own making.

Current Gap CEO Art Peck will lead the everything-but-Old-Navy company after the split. On Thursday he outlined some sensible areas of focus, including attracting younger customers, shoring up its denim business and testing remodeled stores. But the company’s weak track record during Peck’s tenure doesn’t inspire confidence.

Gap has had basically the same problem for the last half decade or so: It doesn’t have the right selection of clothing in its stores. When Peck became CEO in early 2015, he correctly diagnosed that sales at Gap and Banana Republic were suffering because the aesthetic, fit and quality of the garments were off the mark. His top priority, he said, was to fix that.

By late 2017, however, he had other issues. Because of poor inventory management, Gap again had the wrong mix of merchandise. Sales suffered as the ratio of tops to bottoms in stores was off, making it hard to put together an outfit. Stores, executives said, were “overassorted” — that is, cluttered with too many options.

In both cases, Peck said Gap had a handle on things. In August 2015, he told investors, “I am confident that Gap will make significant progress in spring.” But comparable sales remained in decline at the chain when that batch of clothes landed.

With the later operational woes, the company acknowledged early on it would take a while to clean up the mess. During a 2018 second-quarter earnings call, Peck told investors that “the worst is behind us.” In the third quarter, Gap delivered an even steeper drop in comparable sales.

In both these cases, the retailer apparently did not have a thorough understanding of the scale of the problem and how long it would take to repair.

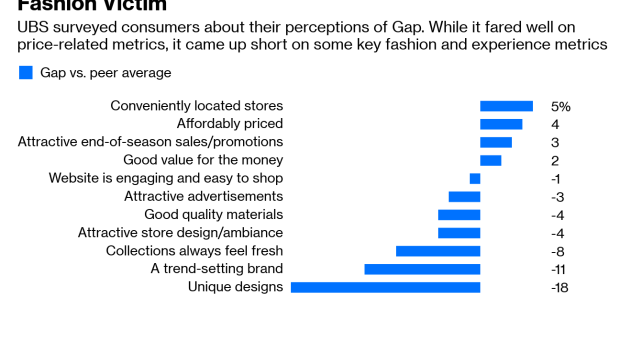

So it’s no surprise, then, it has struggled to get customers to open their wallets. As I noted earlier this year, it lags behind its peers on key indicators of fashion and reputation.

It doesn’t help that Gap has been slow to react to key changes in the larger retail environment. Earlier this year, it announced plans to close 230 stores. Peck rightly noted the move was “overdue”: It had been obvious for years that Gap had too many stores for the digital era and those located in dumpy malls were hurting the brand.

Gap also hasn’t made much progress in restraining itself from offering steep discounts. In 2015, referring to Gap’s near-constant “40% off your purchase” promotions, Peck said, “We've been way too 40 off every day in too many places in this company.” In 2019, these deals are still rampant: The Gap chain has offered a discount every day this month.

Sure, Old Navy has (until recently) enjoyed a steady run of good performance — not insignificant given it is the company’s largest brand. But there has never been a quarter under Peck in which all three of its major stores recorded positive comparable sales.(1)

It’s tempting, of course, to see Gap’s struggles as emblematic of a generally gloomy retail landscape. But compare its trajectory to that of Target Corp. The CEOs of both retailers got their jobs at roughly the same time — Brian Cornell hit his five-year anniversary at the helm of Target in August, a milestone Peck will reach in February.

In that time, Cornell has dramatically improved Target, developing successful private brands, remodeling stores and fortifying Target’s e-commerce division. He made tough choices such as shuttering its disastrous Canada business. Target shares hit an all-time high last week.

Gap certainly has not stood still during the last five years. It has overhauled its supply chain to churn out designs faster and expanded its promising Athleta chain. It has occasionally nailed a trend, such as with last year’s “logo remix” collection. But after years of moving its chess pieces around the board, Gap doesn’t appear to be a fundamentally different retailer. It’s hard to see how its position is improved after this split.

(1) There was one quarter in which Gap had flat comparable sales and the other two major brands saw growth on this metric.

To contact the author of this story: Sarah Halzack at shalzack@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Michael Newman at mnewman43@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Sarah Halzack is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the consumer and retail industries. She was previously a national retail reporter for the Washington Post.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.