Feb 10, 2022

Why Canada no longer reaps the full benefits of high oil prices

, BNN Bloomberg

A rise in oil prices will not likely not bring prosperity to Canada as once before: Economist

The price of crude has hit levels not seen in years, but at least one economist said oil-rich Canada is not reaping the full benefits of these higher commodity prices it has in the past.

Higher oil prices have always been a double-edged sword for Canada. On one hand, it’s positive for our large energy sector but on the other, it means consumers are shelling out more at the pumps while companies see increased input costs.

This time around however, Canada’s energy sector looks very different from previous boom times.

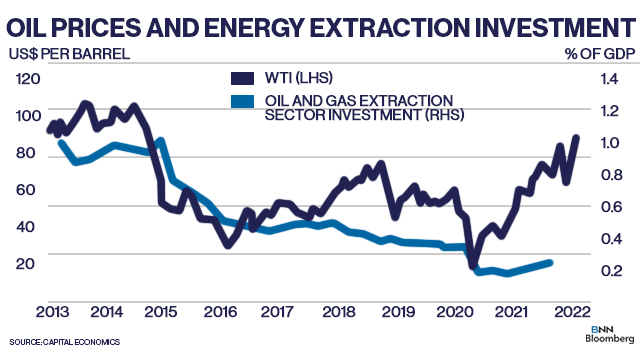

“The oil sector is not the driver of GDP growth that it once was,” said Stephen Brown, senior Canada economist at Capital Economics, in a note released on Wednesday.

“Due to pipeline capacity constraints, there is little supply response to rising prices, with oil production still stuck near 2018 levels. With export capacity out of their hands, producers have been using their income to pay down debt rather than invest.”

He points out capital spending in the energy sector is sitting at 0.3 per cent of GDP, less than a third of what it was in 2014.

Since then, Canadian oil companies have streamlined their operations, implemented more technology, reduced their workforces, and focused on improving their balance sheets.

“As there is little scope for an immediate supply response and it takes time for higher oil export earnings to feed through to the rest of the economy, for example, in the form of higher wages in the oil patch, there is a risk that higher oil prices initially have a modest negative impact on Canadian economic activity, by eating into consumers’ real spending power,” Brown said.

For consumers, higher oil prices mean more of their household budgets will go towards gasoline.

Brown’s price forecast for American benchmark West Texas Intermediate (WTI) this year is US$68 per barrel, later falling to US$63 per barrel in 2023. But if WTI remains closer to the current US$90 per barrel level, his forecast for energy inflation would average 11 per cent this year, more than double his current forecast of five per cent.

“The overall impact would be larger if firms passed on their higher costs to consumers, although these second-round effects would be at least partly offset by the impact of a stronger loonie than we assume, which would pull down imported goods prices,” he said.

However, Brown concluded that even with these dynamics in place, higher oil prices are still a net benefit for Canada, even if it’s smaller than it would have been in previous oil boom cycles.

He said if WTI remained at its current level, his Canadian GDP forecast for this year would nudge higher by a tenth of a percentage point to 3.7 per cent and his 2023 growth outlook would increase by 0.4 percentage points to 2.7 per cent.