Mar 14, 2019

Why central banks like Canada’s are finding it hard to navigate home

, Bloomberg News

Central bankers have long been crafting analogies to explain what they do -- think taking away the punch bowl. Few have been as devoted to the art as Canada’s Stephen Poloz.

He’s trying to steer the economy back to a place where it can support the kind of borrowing costs that counted as normal before 2008. But Poloz’s metaphors often have to do with unforeseen hardships when you’re on the way home -- sailors blown off course, or drivers caught in winter storms. Because, like many global peers, he’s finding the journey hard to map out.

One reason is a feature of today’s developed economies that isn’t normal at all by past standards: their mountain of private debt. Canada has some of the most leveraged households anywhere -- leading analysts to question how much higher rates can go, and even whether they’ve already gone too far.

With five interest-rate increases since 2017, the Bank of Canada is one of a handful to embark on sustained hiking. Poloz has even won international recognition for developing frameworks to manage the process. But there’s been no increase since October, and the Ottawa-based bank said last week that the cycle’s immediate future looks increasingly uncertain amid a global slowdown. Like the Federal Reserve, it’s essentially on hold, waiting to see what happens.

‘I Feel It’

Poloz acknowledges he’s getting heat over higher borrowing costs, in a country where so many households have a direct stake. People write to him. “Believe me, I feel it,’’ he said in an interview. “It’s not a theoretical exercise.’’

That helps explain the folksy analogies -– and also Poloz’s discretionary approach. He shuns the precision of models, sees data more in terms of feeling a pulse than feeding a machine, and recognizes that central banking involves mystery as well as technical expertise.

The goal is to assure as wide a chunk of the public as possible that policy makers won’t hike unless they’re sure the economy can cope with higher borrowing costs. As long as inflation isn’t a threat, they’ll put growth first.

In the global monetary debate after 2008, Poloz has often been on the dovish side -- particularly early in his term.

The concern, then and now, is that cheap money is a zero-sum game. It brings spending forward, but slows it down in the future, and adds financial vulnerabilities -– like high household debt and elevated housing prices in cities like Toronto and Vancouver.

Gauge of Health

Poloz counters by pointing out that the leverage already out there makes tightening risky too. Plus, he sees potential long-term benefits from frontloading demand.

Exports and investment remain below pre-crisis levels as a share of the economy, leaving Canada reliant on consumption and housing. Wage gains are smaller than in the past. The number of new firms being created, an important metric for Poloz, is lackluster. What if Canada’s economy is on the cusp of an investment boom that may not be detectable yet, and companies are holding back because they lack confidence? Productivity typically picks up late in the business cycle, and policy makers shouldn’t get in the way of that by removing stimulus too quickly.

Yet, if the purpose of low rates has been to nurse the economy back to normal, then the ability to raise them should be the ultimate gauge of health.

With the jobless rate at four-decade lows, and underlying inflation back near the 2 per cent target, there were signs that the economy was nearing its capacity -- which is why Poloz began to hike.

Stuck Halfway

The Bank of Canada has been envisaging a final resting place for rates around 3 per cent. But so far it’s only got about halfway there. And as other central banks scale back their expectations, investors are anticipating that Poloz will have to follow.

Markets no longer believe he’ll be able to raise rates any further -- or that Canada’s economy, burdened by heavy debt and aging demographics, can grow much faster than the current, modest pace. Ten-year Canadian bond yields are stuck below 2 per cent, lower even than they were on Poloz’s first day on the job in 2013.

That raises an awkward question for Poloz, and maybe for some of his central-bank peers too: Has monetary policy already done all it can?

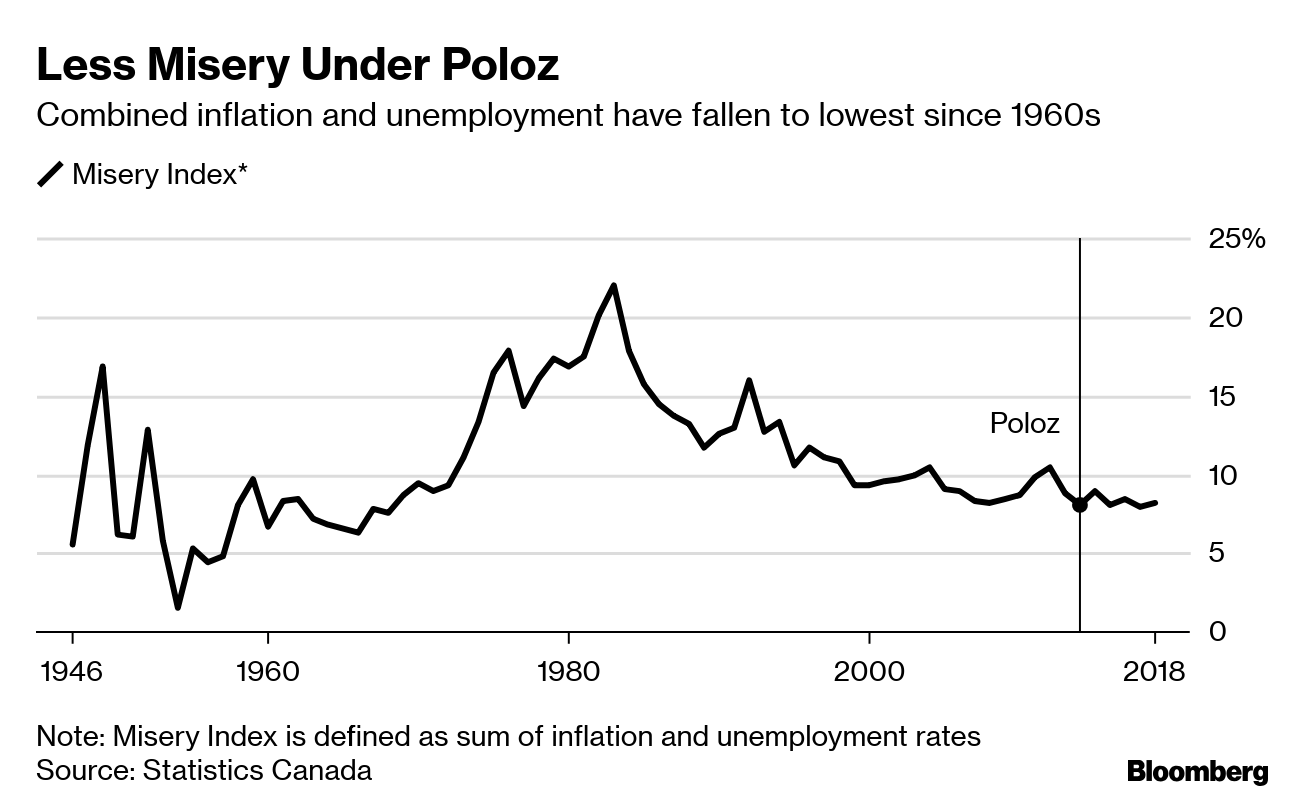

As he prepares to enter the final year of his seven-year term, Poloz could lay claim to be one of Canada’s most successful central bankers ever. The country is closer to a state of full employment and stable prices than at any time since the 1960s –- exactly the sort of benchmarks policy makers are supposed to aim for.

It’s just that one of the slowest recoveries on record wouldn’t be a very satisfying finish line. Most economists currently put potential growth at no higher than 2 per cent. In the last six quarters the economy hasn’t even managed that, averaging 1.6 per cent.

As well as telling stories about journeys home, Poloz also likes to invoke “Mother Nature” and argue that economies are capable of regenerating themselves. In the interview, he expressed confidence that Canada can climb back toward the faster growth it once took for granted -- if “all the ingredients work out.’’

“I see no reason why we should settle for our 2 per cent trend-line,’’ he said.

--With assistance from Erik Hertzberg.