Sep 12, 2019

Will Brexit Trigger England’s Second Civil War?

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- At the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642, Warwick Castle was attacked by soldiers loyal to the king who tried without success to unseat the Parliamentarian forces that held it. While a minor skirmish, the outcome would foreshadow the broader struggle for the country.

Today, the town of Warwick is under siege of another kind, one that may similarly decide where the divided nation is headed after an escalation in the political drama over Brexit.

The U.K. is witnessing an historic period of upheaval that has invited comparisons with events almost 400 years ago. Parliament has been suspended – illegally, a court in Scotland ruled on Wednesday. The prime minister is threatening to flout the law to get his way while lawmakers on all sides are in open revolt and Ireland’s future, north and south, is at stake. Even the Queen has become embroiled in the standoff. And violence is brewing, with scuffles outside Parliament last week.

Lawmakers this week channeled an event from the runup to the civil war in the House of Commons to protest the so-called prorogation of the legislature. Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage, one of the main architects of the vote to leave the European Union, has described the present constitutional crisis as the worst since that tumultuous period.

A tour last week through some English counties scarred by the conflict suggests he may be right. With positions hardening and no obvious release for rising tensions, it’s anybody’s guess where the Brexit dilemma ends.

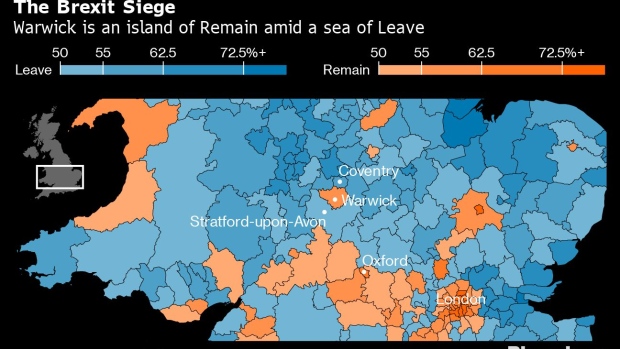

Voters in Warwick opposed leaving the EU, seeing a departure as a threat to a key employer — the automotive industry — and to the university town’s international outlook. But as a pro-EU bastion amid a sea of Brexit territory, Warwick is at odds with neighboring districts, the U.K. as a whole and with Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s Conservative government. Those same divisions run through swaths of the country.

“If we get out of the current impasse without shots being fired, we will be doing better than I expected,” said Diane Purkiss, author of “The English Civil War: A People’s History” and a professor of English literature at Oxford University. “The question from here is whether we can at the last minute and in the eleventh hour muddle together some kind of final British compromise.”

With its timber framed houses, country parks and association with William Shakespeare, the county of Warwickshire is picture postcard England. But beneath the patina of Olde Worlde charm lie stark divisions in attitudes to Brexit.

Of course the U.K. has always diverged along political lines, from Thatcherism to Blairism. What attracts today’s comparisons with the 17th century is the constitutional chaos on top. Then, the country chose sides as Parliament and Oliver Cromwell’s Puritans asserted authority over King Charles I and his Catholic household in a standoff over religion and power that ultimately led to war and regicide.

In an echo of Brexit’s patchwork of “leave” and “remain” voting areas, the civil war cleaved along the lines of individual towns and cities depending on which way they declared, for Parliament or the King. Indeed, the political map of the Brexit vote resembles the distribution of support for both sides in the civil war, Stefan Collignon, a professor at the London School of Economics wrote in March last year.

In Warwickshire, Stratford-upon-Avon was sandwiched between Parliamentarian and Royalist forces, and took in casualties from the war’s first major battle at Edgehill.

Stratford, Shakespeare’s birthplace, is a 20 minute drive to the southwest of Warwick but a different world in its Brexit outlook. Whereas Warwick and its surroundings are home to workers from the nearby Jaguar Land Rover plants and left-leaning, pro-European students and academics from Warwick University, Stratford relies on tourism, the hospitality industry and foreign workers to staff it.

Warwick voted 59% to 41% in favor of remaining in the EU. Stratford voted 52% to 48% to Leave, bang in line with the country as a whole.

Walking around Stratford, past the Tudor houses and boats on the river Avon, there is little outward evidence of tension. That’s no comfort to Sophie Clausen, an artist and author originally from Denmark who first came to Britain as an art student in 1984.

For Clausen, that sense of indifference cannot be excused by any amount of Brexit fatigue, and is the most worrying aspect of all. “People switch off, they don’t care, and that’s really dangerous,” she said.“People say they just want Brexit over with, but I don’t think it will ever end,” said Clausen. “Because if it doesn’t happen, the divisions will get even deeper and people who voted Leave will be even more angry,” she said. “No-one knows the way out any more.”

Johnson has a little over a month to try and strike a new deal with the EU that’s palatable to enough parliamentarians to enable Britain to leave the bloc in an orderly way on Oct. 31. If he fails to do so, he is now required by law to ask for an extension, something that will almost inevitably lead to the general election he wants to break the impasse.

QuicktakeHow to Follow the Latest Brexit Twists

Comparisons between Johnson and Charles I over their treatment of Parliament are unhelpful, according to Purkiss, the civil war author, since the king waited 11 years to recall the legislature rather than the present five weeks. Yet there is a common “persistent ongoing failure of compromise” that contributed to the descent into conflict, she said.

Other parallels lie in the existence of concurrent crises in “the three kingdoms” of England, Ireland and Scotland; and in the emergent print media’s alarmist headlines that mirror today’s social media posts, “weaponizing fear mongering,” said Purkiss. “I don’t think people are taking this threat seriously enough,” she said in an interview at Keble College in Oxford, one block away from St. Giles Church, which carries a plaque describing its damage in the civil war.

At root, Brexit is the symptom of a crisis of parliamentary democracy, with both main parties pushed to extremes and the middle ground erased, eroding willingness to reach consensus. That presents a challenge for politicians like Jack Rankin, selected to contest the Warwick and Leamington constituency for the Conservatives at the next election.

The district was held by the Conservatives for much of the 20th century, falling to Labour in 1997 as the Blair government came to power, and has changed hands between the two parties since. Matt Western retook it for Labour in 2017 with a majority of just 1,200 votes.

His pro-European views were reinforced by a previous life as a marketing manager for French carmaker Peugeot in places like Vienna and Paris. Bridging the division “is very hard because both sides of the debate are becoming quite entrenched in their view,” said Western. “I’m really alarmed about what’s going on in society,” he said.

To win the seat from Labour, Rankin, who voted for Brexit, will have to appeal to a strongly anti-Brexit electorate.

He said that his experience on voter doorsteps shows “the overwhelming majority are fundamentally democrats and just want to get on with it.” The divisions are not as deep as commonly presented, he said in an email response to questions, and healing the Conservative rift “won't happen until we deliver what we said we would.” He said the future is bright regardless of how Brexit plays out.

That may be wishful thinking. Jaguar Land Rover CEO Ralf Speth warned last year that a bad Brexit could put tens of thousands of jobs at risk. Warwick University’s Vice Chancellor Stuart Croft has called Brexit a “disaster” and said that losing access to international research networks could shut the U.K. out of the science vanguard and risk jobs.

The warnings were not lost on Barry Archer, a maker of clay models used in car industry design who has worked across Europe, most recently for Skoda in the Czech Republic. He was at a “Stop the Coup” demonstration last week in Coventry, the city whose outskirts include Warwick University’s leafy campus, to protest the proroguing of Parliament. Archer was among the 200 or so who showed up.

His latest job was canceled as a result of the uncertainty over Brexit. His two adult sons feel their future is being settled without their say, with freedom of movement set to go in the name of the “will of the people.” For Archer, Brexit is personal – his wife is German – but he still doesn’t see any chance to roll it back.

“The problem is it’s divided the country so much there’s going to be no easy way around it,” he said as an autumn wind blew in the city’s Friargate. “Damage to the foundation of who we are, what we are has been done. It’s just damage control now.”

Bernard Capp, an emeritus professor of history at Warwick, has seen the university’s development from its earliest days in the 1960s and still teaches a class on radicalism and the English Civil War. He sees parallels with the sort of polarization witnessed between 1640 and 1642, when the war broke out, and says that’s a cause for concern.

During the civil war, Coventry was a Parliamentarian center, known for its extensive medieval city walls. Capp related that Charles I arrived in late summer 1642 on his way to raise an army, and demanded entrance. The mayor of Coventry refused, the first real act of defiance before the fighting started.

“We should all be very wary because nobody wanted a civil war, nobody expected a civil war and look where that happened,” he said. Even at the war’s end, “no one thought there would be a revolution and the king would get his head chopped off, and yet that’s where it ended up,” he said.

“So no one knows what the final destination will be once you get into a constitutional crisis.”

To contact the author of this story: Alan Crawford in Berlin at acrawford6@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rodney Jefferson at r.jefferson@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.