Sep 4, 2019

Will they help, hurt or do nothing? Central banks face backlash

, Bloomberg News

Central bankers aiming to 'give the ducks what they're asking for' with rate cuts

Investors are increasingly signaling they don’t buy the inflation-boosting policies central banks are selling, with some even fretting stimulus may do more harm than good.

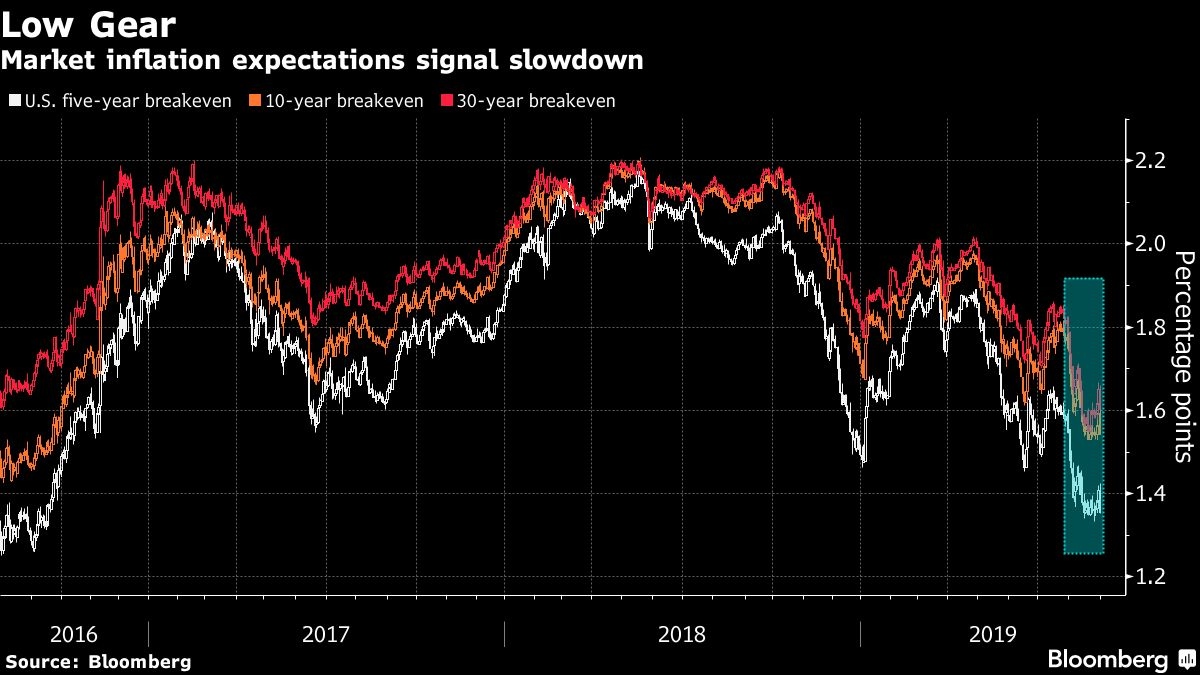

Falling expectations for consumer-price growth, plunging bond rates and flatter yield curves all point to mounting doubts in financial markets over whether monetary policy makers have what it takes to reflate their economies and avert a global recession. “Quantitative failure” topped investor concerns in a Bank of America Merrill Lynch survey last month.

It’s all raising the stakes as the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank and potentially even the Bank of Japan get ready to announce easier policy as soon as this month.

“What markets are telling us is that they don’t expect central banks to be able to raise inflation now,” said Naoya Oshikubo, senior economist at Tokyo-based Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Asset Management Co., Asia’s largest asset manager. “Central banks need to regain credibility.”

Such doubts are festering even after central banks delivered more than 700 interest rate cuts over the last decade and spent trillions buying bonds. While that helped dodge a depression following the 2008 financial crisis, price pressures remain muted and most major economies undershoot policy makers’ inflation targets.

In Japan, for example, inflation is 0.6 per cent despite its central bank introducing negative interest rates in 2016. In South Korea, consumer price growth fell to zero for the first time ever in August as the nation got caught in growing trade tensions. The International Monetary Fund recently pared its prediction for inflation across advanced nations to show it averaging just two per cent next year.

Even with the Fed having recently cut its benchmark for the first time in a decade and the ECB set to follow this month, long-term inflation expectations as proxied by five-year, five-year forward inflation swaps have fallen in the U.S. and are near a record low in the euro region.

That probably partly explains why investors are demanding virtually no additional compensation for inflation risk to hold longer-dated bonds instead of shorter maturities. The yield spread between two- and 30-year Treasuries has dropped to 52 basis points, compared with an average of 232 basis points in the past decade. The yield on 50-year Swiss bonds has turned negative.

Central bankers face a credibility gap as they take stock of depleted arsenals. The Fed’s benchmark, for example, is about half the level it was before the last recession.

Like the BOJ, the ECB’s key rate is already in negative territory. Buying bonds may no longer have the impact it once did: Signals of stimulus from Mario Draghi, whose policies helped lift Europe’s economy from its 2012 depths, have done little to inspire traders’ confidence.

“At this stage it’s not clear whether doing something is actually going to help, hurt or do nothing for the economy,” Steven Englander, who runs G-10 foreign-exchange research at Standard Chartered Bank, said in an interview with Bloomberg TV. “There’s a lot in the market that says you do too much stimulus, it inverts and you stop getting any benefit.”

Then there are doubts over what power policy makers have in the current economic environment. For one thing, the escalating trade war and political crisis in the U.K. and Italy are sowing uncertainty that may not be offset by lower rates.

“Hurdles for successful reflation are high and rising,” Morgan Stanley strategists led by Hans Redeker wrote in a report last week. In another released Tuesday they warned of “reversal” rates at which easier monetary policy ends up dampening rather than stimulating economies.

That’s led investors to suggest more fiscal stimulus is needed to avoid over-reliance on low interest rates. They fear that keeping rates too low for too long could sap rather than spur growth by creating asset bubbles, hampering banks and eroding returns for pensioners, insurers and savers.

Roelof Salomons, chief strategist at Kempen Capital Management in Amsterdam, says low rates may end up doing more harm than good by keeping unprofitable or “zombie” companies alive. “If there is one thing that keeps me up at night, it’s the risk that the ultra low rates will become a vicious circle,” he said.

Consumer and corporate debt running at 225 per cent of global GDP, according to IMF estimates, is another reason to think cheaper credit won’t stir animal spirits. Negative rates outside of the U.S. hamper commercial banks’ ability to lend.

There may also be longer-term forces in play. Globalization, aging populations and digital disruption threaten to depress inflation regardless of what monetary policy levers are pulled.

Central bankers continue to argue they have what it takes.

In her first comprehensive comments on monetary policy since winning the job, incoming ECB President Christine Lagarde said last week that the institution has the tools to tackle a downturn and must be ready to use them if needed.

And markets expect them to at least try. Banks including Nomura Holdings Inc. and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. expect the ECB to also cut rates and restart quantitative easing. Fed funds futures indicate just over a quarter point of easing priced in by the end of September. JPMorgan Chase & Co. is anticipating action from the Bank of Japan this month too.

Economists at Goldman Sachs are also warning the “inflation puzzle” is exaggerated and in a report published Tuesday argued that goods inflation excluding food and energy is actually growing in advanced economies outside of the U.S. by the fastest in 30 years.

If central banks do flop, governments will come under pressure to step up in the hope greater spending or cheaper taxes will juice economies by enough to get inflation going.

“Short of a fiscal stimulus, treating additional monetary easing as a net negative becomes a consensus view, with self-fulfilling effects on the economy via confidence,” said Gilles Moec, chief economist at AXA SA. “In any case, this is another reason to believe monetary policy is now generating only marginally positive returns at best.”

--With assistance from Jonathan Ferro, Simon Kennedy, Liz Capo McCormick and Tanvir Sandhu.