Dec 4, 2018

With US$800-an-ounce bud, pot artisans go high end

, Bloomberg News

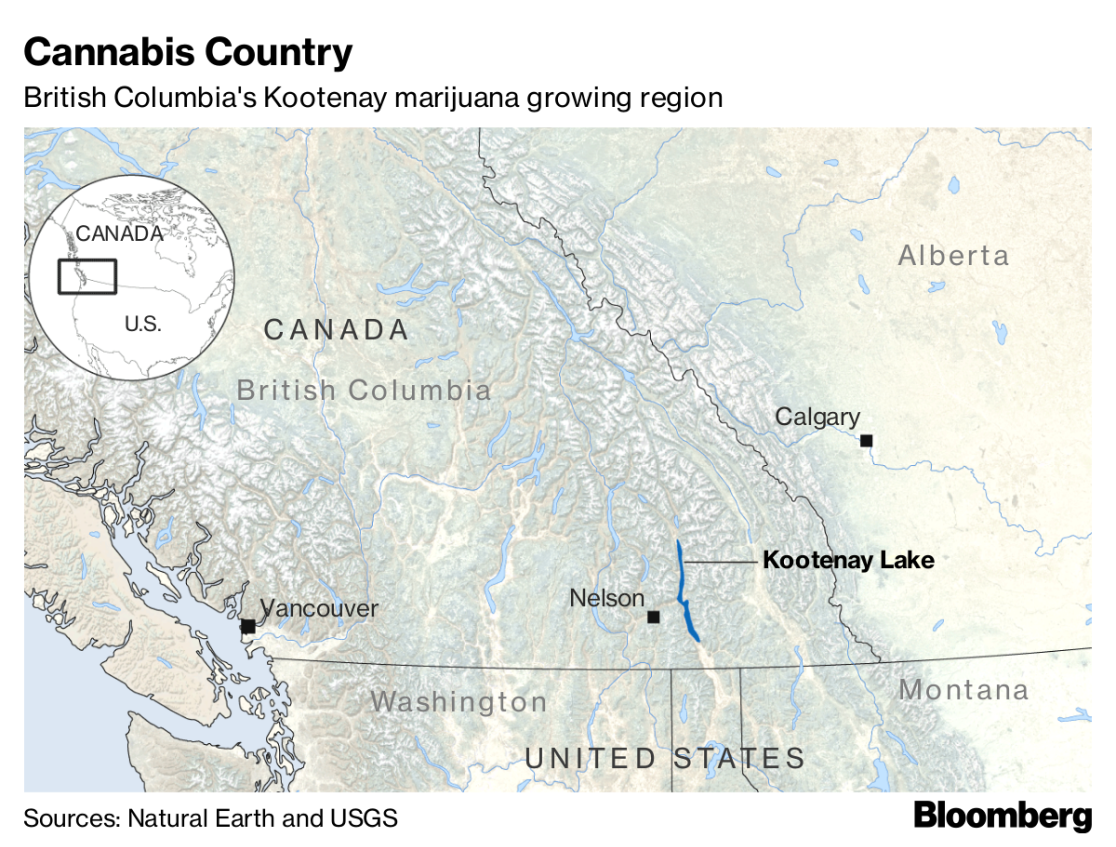

Take a 35-minute ferry ride across the impossibly clear glacial waters of British Columbia’s Kootenay Lake, and you’ll find yourself on the East Shore. For generations, lush tracts of marijuana flourished here along the abandoned logging roads that snake through its craggy mountains.

Not long ago, police would rappel down from helicopters to hack away and pour bleach on the illicit crop. Kevin McBride, a rugged 51-year-old wearing gumboots and a wool cap, can recall those inevitable autumn raids.

These days, McBride reaps the region’s most prized harvest, the Moet & Chandon Champagne of pot. Connoisseurs in Amsterdam coffee shops pay as much as 25 euros a gram (US$805 an ounce) for the best strains, considered among the world’s finest. Most artisans now raise their weed indoors. A legal grower with a medical license, McBride works out of the basement of his garage after learning the craft from a “crazy old uncle” and other doyens of what is known as “BC Bud.”

In Canada, the first major industrialized country to legalize recreational pot, this remote region illustrates the opportunities and challenges facing these artisans: Can they develop their industry without selling out to the Toronto “suits” who increasingly dominate the trade?

With stunning valleys ringed by snow-capped peaks and a relaxed outdoorsy vibe, the Kootenay region already draws visitors. It’s easy to imagine tasting tours featuring pot sommeliers who offer guidance on the subtleties of the region’s brands. Care for a puff of “Captain Ahab”? It promises a pungent lemon aroma and an energizing daytime high.

“For us not to brand what we have here is ludicrous,” says McBride, who is seeking a micro cultivation license for his company, Kootenay’s Finest. His target customer? “Not the Budweiser market.”

Worldwide recreational cannabis sales could reach $120 billion by 2025, according to brokerage firm BMO Capital Markets. In October, Canada’s legalization gave it an edge over the U.S., where pot is permitted in 10 states and the District of Columbia for recreational use while the federal government still outlaws it. Some 149 pot companies valued at about $52 billion have already listed on Canadian stock exchanges.

Bruce Linton, chief executive officer of Canopy Growth Corp., one of the world’s largest pot producers, predicts consolidation will leave one “Google-like company” in the cannabis industry and a smattering of “craft players.”

In Nelson, a town of 10,000 whose streets are lined with Victorian houses, the joke is that every second house is already a craft player.

“I’ve completely underestimated the potential of the industry, as many people have,” says John Dooley, Nelson’s mayor, who opposed cannabis until legalization day.

Once a silver mining outpost, then a logging center, the region has long been a place of refuge, settled by Russians fleeing the czars, pacifist Quakers, and Japanese Canadians released from World War II prison camps.

Hippies and Vietnam War draft dodgers started trickling in during the 1960s. They discovered a land supremely suited to marijuana. The Kootenays’ wet springs nurture the plants, dry intense summers kill the mold and cool autumns concentrate the essential oils known as terpenes that give weed its flavor and smell.

Today, the region produces some 25,000 kilograms a year of pot, enough for 50 million joints. It could amount to an eighth of Canada’s expected annual production in legalization’s first year. Or, at least, that’s David Robinson’s estimate.

His guess is as good as any. For 15 years, Robinson has been selling hydroponic equipment from the Nelson branch of Pacific Northwest Garden Supply, one of the province’s biggest retailers of pot paraphernalia.

Robinson, 43, looks more like a high-energy entrepreneur than a laid-back stoner. He has closely cropped blond hair and a physique honed by Pilates and jiujitsu.

Still, he reveals hints of the counterculture. Robinson wears a coyote tooth on a red-beaded necklace. It’s a memento from a 10-day spiritual journey in Peru aided by ayahuasca, a hallucinogenic brew of Amazonian plants. Known as the “Garden Sage” for his must-read grower’s handbook, he says the opportunity is there for the taking.

“We have to step up to the plate, capitalize on the history and reputation that we’ve built,” Robinson says. “We’ve got a chance to be first to market. Everyone’s talking the Canadian market right now, but I’m thinking about the world — think of coffee, think of tea. This could be huge.”

Cultivating craft cannabis requires art and science.

In a humid shed nestled in the Slocan Valley, west of Nelson, Paradise Valley Botanics has been growing pot under Canada’s medical program for more than a decade and a half.

The owner requested anonymity, underscoring the ongoing stigma of the drug trade. He cultivates in small batches. To stimulate faster growth, a carbon dioxide tank enriches the air to about four times the normal level. Harvests are slow-cured, like slabs of pork. For two weeks, the plants hang upside down, concentrating the terpenes into the flower.

But the true genius of the artisans lies in manipulating the plants’ genetics. They select and cross-breed specimens to achieve a certain scent, color, potency or yield. A varietal called Blood Orange, for example, has the tang of freshly peeled citrus. Another produces flowers with vibrant fuchsia specks. Indica plants, like a full-bodied shiraz, offer a heavier, mellow buzz.

In contrast, the biggest licensed producers take a factory-style approach in greenhouses as big as 22 football fields. Water, light and temperature are automatically controlled, the product sterilized with gamma rays.

Small-time growers face high hurdles. Legalization introduced a byzantine web of regulation and the rise of well-funded corporate rivals such as Canopy, Aurora Cannabis Inc. and Aphria Inc. In recent weeks, executives from Aurora, Aphria and Ascent Industries Corp. have been pitching partnerships, drawing crowds in Nelson of as many as 150 people.

“People here are freaking out that their livelihoods are being taken away by Bay Street suits,” says Robinson, referring to the heart of Canada’s financial industry in Toronto. “They’re moving the money out east.”

To comply with municipal regulations, McBride, the medical grower, had to buy a new 60-acre (24-hectare) plot. There, rather than expand his existing shed, he has to build a structure ringed with a 30-meter (98-foot) buffer. That rule alone will probably bar most craft growers in the area from legalizing their current operations, he says.

McBride expects to spend more than $1.3 million on the property, constructing a new building and meeting other standards such as installing chain-link fences and bar coding for every plant. Money is scarce. Many banks still shy away from lending to marijuana companies.

Canada also decides which seeds are legal — precious few, for now. If craft growers are unable to get licensed, their varieties will be lost to the legal market.

“It’s like saying beer is legal but you can only drink Pilsners,” McBride says. “The black market will just mushroom.

--With assistance from Kristine Owram

Cannabis Canada is BNN Bloomberg’s in-depth series exploring the stunning formation of the entirely new – and controversial – Canadian recreational marijuana industry. Read more from the special series here and subscribe to our Cannabis Canada newsletter to have the latest marijuana news delivered directly to your inbox every day.