Nov 29, 2020

Worse Than Covid? Risks to U.K. Economy as Brexit Deadline Nears

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- With the U.K. economy suffering more from the coronavirus than most advanced nations, the stakes couldn’t be higher as Brexit trade negotiations enter their endgame.

Gross domestic product will likely be smaller than what it would have been had the U.K. stayed in the European Union regardless of the outcome. But reaching an accord would help avoid major trade disruptions come Jan. 1.

Leaving without a deal, meanwhile, means that Brexit could end up inflicting more lasting damage than the pandemic, according to economists. Both sides say the onus is on the other to make a decisive move before the transition ends in just over a month.

The following charts illustrate what’s at stake for the U.K. economy.

The pandemic has put Britain on course for its deepest economic slump since the Great Frost of 1709. By the first quarter of 2025, GDP will be 3.1% lower than anticipated in March, according to estimates by the Office for Budget Responsibility released on Wednesday. The fiscal watchdog deems the loss of output to be permanent.

In a separate analysis, the OBR said transitioning into a free-trade agreement with the EU would shave 4% off GDP in the long run. A no-deal scenario -- meaning a shift to World Trade Organization rules -- would mean losing another 1.5%. Dan Hanson of Bloomberg Economics puts the combined cost higher still, at 7% of GDP.

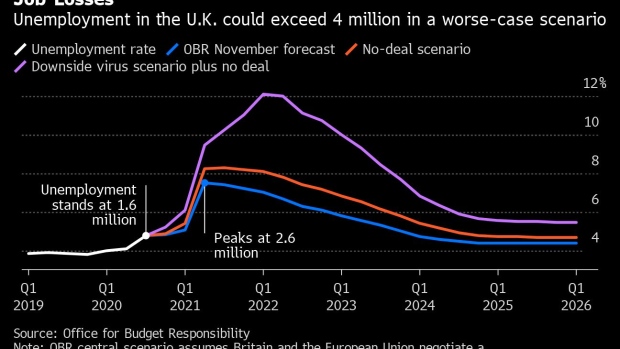

Jobs are also on the line. Unemployment is set to peak at 7.5%, or 2.6 million people, next year under the OBR’s central scenario that a trade deal be reached. A no-deal exit pushes the rate up to 8.3%.

Financial services and export-reliant manufacturing sectors such as the car industry, food and textile producers stand to be among the hardest hit if trade talks fail.

There are concerns that the time and money spent dealing with the pandemic has left many firms ill equipped to cope with the potential costs and disruptions ahead. A Bank of England survey of chief financial officers last month found less than 4% of them were fully prepared for the end of the transition period.

Before the pandemic, businesses were already holding back on spending as they awaited greater clarity over Britain’s post-divorce relationship with Europe. Now Covid-19 has added to the difficulties, decimating investment this year and risking their ability to do so in future.

No matter what the outcome of the talks, a period of adjustment is likely to make it hard for companies to know how best to invest for the future, but a move to WTO terms risks keeping spending depressed for longer, hitting already weakened productivity.

The bigger the economic shortfall, the bigger the persistent budget deficit that Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak needs to fill.

Even if a trade deal is struck, balancing day-to-day spending and revenue by the middle of the decade will require 27 billion pounds ($36 billion) of tax increases or spending cuts, according to the OBR. That figure could rise to 34 billion pounds if firms are hit by new tariffs and curbs on trade with the EU.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.