Nov 9, 2021

Cost of Capital Spikes for Fossil-Fuel Producers

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) --

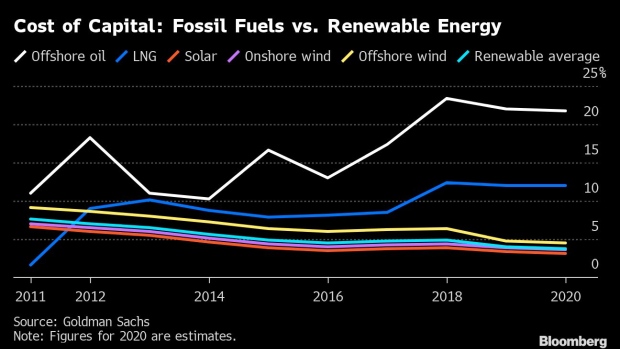

Ten years ago, the “cost of capital” for developing oil and gas as compared to renewable projects was pretty much the same, falling consistently between 8% and 10%. But not anymore.

The threshold of projected return that can financially justify a new oil project is now at 20% for long-cycle developments, while for renewables it’s dropped to somewhere between 3% and 5%, according to Michele Della Vigna, a London-based analyst at Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

“That's an extraordinary divergence which is leading to an unprecedented shift in capital allocation,” Della Vigna said. “This year will mark the first time in history that renewable power will be the largest area of energy investment.”

Will Hares, an analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence, said pressure from ESG investors is the best explanation for the widening difference between dirty and clean.

“Oil companies are finding it increasingly difficult to raise financing amid rising ESG and sustainability concerns, while banks are under pressure from their own investors to reduce or eliminate fossil-fuel financing,” Hares said.

This is resulting in more expensive debt financing (in some cases double-digit coupons), which, when coupled with depressed equity valuations, leaves most oil companies facing higher costs for capital, Hares said.

Climate finance has been a hot topic at the COP26 meetings in Glasgow, Scotland. Government leaders from less-developed nations have at times expressed fury that rich countries repeatedly break promises to mobilize funds to help them decarbonize and adapt to a warming planet.

More such pledges were made last week—only this time they came from the financial industry.

Mark Carney, the former central banker turned climate envoy, said more than 450 financial firms representing $130 trillion of assets have pledged to bring their lending and investing activities in line with the goals of the 2015 Paris agreement. The announcement, however, didn’t mollify skeptics who are quick to point out that details on how the industry would actually meet this target were lacking—a hallmark of the greenwashing scourge.

Goldman Sachs estimated that about $56 trillion, or $1.5 trillion to $2 trillion a year, will be invested in renewable energy, bioenergy and other clean-energy infrastructure projects between now and 2050. Spending is expected to peak between 2035 and 2040, driven largely by expenditures on power networks, charging networks, building upgrades and a massive expansion of renewable power sources such as clean hydrogen, Della Vigna said.

“It's significant that such a large share of the financial sector has recognized its role in driving the climate crisis and the need to wind down its financed emissions,” said Ben Cushing, a campaign manager at the Sierra Club, an environmental pressure group. “But achieving net zero by 2050 and staying within 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming means stopping financing for fossil-fuel expansion today. That’s the key test for whether these commitments are aligned with reality.”

It’s likely that given this backdrop, the spread between oil, gas and coal and renewable energy will continue to diverge as banks change their financing habits. Indeed, markets may end up killing off fossil fuels before governments do.

Sustainable finance in brief

- Adam Smith’s “Wealth of Nations” gets an update to accommodate the climate crisis.

- Former U.S. Vice President Al Gore warns the world about a multitrillion-dollar “subprime carbon bubble.”

- Singapore aims to curb greenwashing by way of stress test technology.

- Lazard Chief Executive Officer Ken Jacobs says he seeks to plug the green knowledge gap.

- World Bank’s Climate Warehouse is looking to blockchain technology to solve carbon data issues.

Bloomberg Green publishes the ESG-focused newsletter every week, providing unique insights on climate-conscious investing.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.