Feb 22, 2020

France Closing Its Oldest Nuclear Plant Spurs Debate on Energy

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- France’s decision to shut its oldest nuclear reactor is stirring controversy about whether President Emmanuel Macron is making the right decisions to reduce fossil fuel pollution and meet climate targets.

The closure of a 43-year-old unit in Fessenheim on Saturday takes out of service just one of France’s 58 reactors. Macron is encouraging wind and solar farms to play a bigger role in the future, promising to shut more atomic plants toward the end of this decade when they reach a half century in service.

Scaling back nuclear, which feeds about 70% of electricity to France’s grid, will probably result in natural gas getting a bigger foothold in what has historically been one of the cleanest power systems in the world. Critics are concerned that scrapping those steady flows for renewables that only work when it’s sunny or breezy will leave France more dependent on fossil fuels at a time when there’s pressure to zero out emissions by 2050.

“One can speak of an environmental mistake,” said Florent Nguyen, an energy and utilities expert at Oresys, a French consultant. “Politics has prevailed over environmental emergency as we’ll see an increase in CO2 emissions.”

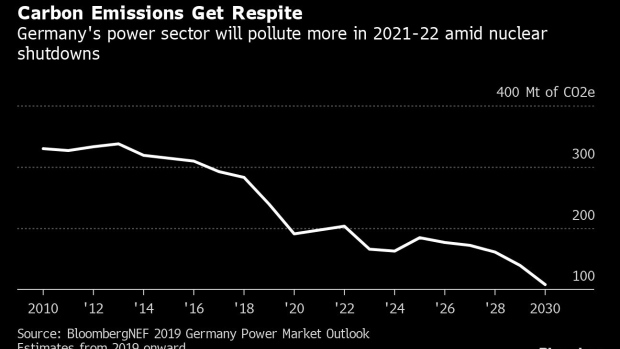

It’s a pattern emerging elsewhere in Europe, which is targeting the power sector as one of the prime ways of reaching a net-zero target by 2050. Germany and Belgium are poised to see a rebound in pollution from plants fired by coal and natural gas. Those fossil fuels will fill a gap on the grid as nuclear plants retire before solar and wind farms reach the needed scale.

Retiring the plant at Fessenheim along France’s border with southern Germany already has taken many years. A second reactor there will shut in June. Macron’s predecessor first made the pledge to halt the plant to get the Green party’s support in the 2012 presidential election.

A dozen more reactors will halt by 2035 to make room for more solar and wind power, Macron has decided.

Germany opted a decade ago to progressively halt its nuclear plants by the end of 2022. Its effort to scrap coal and lignite as power generation fuels will take until 2038. Belgium is considering building gas-fired generators to partly replace its atomic plants due to be halted from 2022.

Germany’s decision led to more electricity generated from coal, lignite and gas, “and thus to an increase in CO2 emissions and local pollution, the health effects of which have not been considered,” Claude Crampes and Stefan Ambec, professors at Toulouse School of Economics, wrote this week. It also contributed to higher electricity prices.

Macron’s government is confident that halting the two Fessenheim reactors won’t boost emissions in France because the development of renewables is quickening. However, given that France is a net electricity exporter for most part of the year, the nuclear production shortfall may end up boosting emissions in neighboring countries that are more reliant on fossil fuels.

Replacing the Fessenheim reactors’ output with coal-fired generation would release 10 million tons of CO2 per year, according to Electricite de France SA. By comparison, France’s entire power sector emitted just 19.2 million tons last year, less than a 10th of Germany’s, as electricity was mainly produced with nuclear and renewables.

But burning coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel, is looking less likely in France. Falling gas prices and the rising cost of emission permits displaced some coal generation last year, and France plans to shut down its remaining four coal-fired power stations in the next couple of years.

“2019 saw a spike in coal-to-gas fuel switching across Europe,” said Antoine Vagneur-Jones, an analyst at BloombergNEF in London. “It’s fortunate that reactor closures are being carried out at a time when gas is particularly competitive, dampening the resulting upwards pressure on emissions.”

The initial plan was to replace the two 900-megawatt reactors at Fessenheim by a 1,650-megawatt atomic plant in Flamanville. Commercial operations of the new facility in western France has been delayed until mid-2023 because of a series of construction issues.

As a result, EDF, which operates all of France’s atomic plants, said its nuclear output may fall again this year as it closes the two Fessenheim units, unless it better copes with maintenance halts.

“In the next two or three months, we’re going to see a rise in CO2 emissions,” said Nicolas Goldberg, an energy analyst at Colombus Consulting. “In the long term, with the deployment of more renewable energies, energy savings and the exit from coal, I don’t think we’ll have a rise in CO2 emissions, though the climate performance will be slightly weaker than if we had kept Fessenheim.”

To contact the author of this story: Francois De Beaupuy in Paris at fdebeaupuy@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Reed Landberg at landberg@bloomberg.net, Andrew Reierson

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.