Feb 4, 2023

Why Is Britain Taking the Axe to Wood-Burning Stoves?

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) --

For generations, British homes have been warmed by log burners. These wood-burning stoves are more efficient and less sooty than open fireplaces; they also offer rustic aesthetic appeal with no cumbersome oil delivery or need to connect to a gas grid. But burning wood to stay warm has a downside: Concerns about air quality and pollution are now driving interest in tougher regulations.

As the UK works to meet a legal target to reduce population exposure to fine particulate emissions by 35% by 2040, compared to 2018 levels, the government is planning to tighten rules on wood-burning stoves, reducing the maximum amount of smoke per hour emitted by new models from five to three grams in specific high-risk areas. It also suggested that councils should be more proactive in enforcing penalties for rule-breakers, using new powers to issue immediate fines rather than taking an offender to court.

Over the past few years, log burners have seen an uptick in sales in the UK amid skyrocketing costs for gas and electricity, making them one of few sources of fine particulate emissions that has actually increased. But despite calls from clean air groups, the government says it is “not considering a ban on domestic burning” across England. The smoke emissions limit applies to certain areas, mostly in cities and towns, where air pollution is a particular problem. Here, burning in general tends to be banned apart from exempt appliances, and the update further limits which log burners are considered exempt.

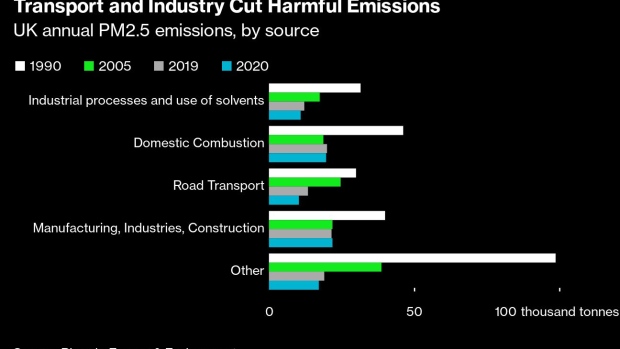

Since 1990, the average concentration of total fine particulate matter emissions (PM2.5) across the UK has shrunk, due in part to cleaner energy and industrial processes as well as tighter regulations on tailpipe emissions. But the proportion of PM2.5 coming from home wood burning has risen steadily even as other sources have fallen.

Rob Gross, director of the UK Energy Research Centre, a publicly funded academic group, said people may actually be installing wood-burning stoves because they think it’s a more sustainable thing to do — and “in some respects it is” — because trees absorb carbon as they grow, making them less of an issue for climate change than fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas. “There’s been a little bit of culture war involved,” he said. “There was a sense that worrying about wood-burning stoves was perhaps a bit ‘nanny state’-ish. That view appears to have shifted.”

Evidence about the health implications of PM2.5 has been building since the 1990s, when a US study found that people in a heavily polluted Steubenville, Ohio, died several years younger than those in the least polluted cities. Later research linked high levels of fine particulate exposure to heart and lung diseases including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, as well as pregnancy complications and dementia.

In the UK, wood used as fuel accounted for just 3% of PM2.5 emissions in 1990. In 2020 it was 17%. There is also concern about the health impacts for the young and the elderly, and for people spending significant time in homes heated by wood or coal. Meanwhile, evidence is rising that even cleaner-burning fuels such as natural gas can have damaging effects. A US study from December linked roughly 12% of childhood asthma cases to cooking with natural gas.

A surprisingly high proportion of the air pollution in urban areas comes from log burners. Data from 2019 in London shows that domestic wood burning makes up around 16% of the fine particulate matter in the city, most of which comes from the city’s suburbs. That’s three times the contribution from domestic gas heating and cooking, and around half the levels contributed by road transport, including cars and trucks.

Data from industry body the Stove Industry Association (SIA) shows a 40% rise in sales of wood-burning stoves last spring — with more than 35,000 units sold — compared to the same period the previous year. The group says people are seeking an alternative source of energy during a crisis that has pushed oil and gas prices higher and exposed the flaws in the global energy market. Overall, around 2 million UK households use wood as fuel, with roughly half of those using a closed stove rather than an open fire.

James Garnett, a salesman at UK stove company Clearview, said he’s been fielding worried calls from customers. “I think it’s going to be very hard for councils to prove that someone has been using a stove above the limit” of three grams of smoke per hour, he said, adding that the government should focus instead on encouraging anyone with an open fire to get a log burner instead. “It’s unfair to be lumping stoves and open fires together.”

Enforcement would indeed be difficult, according to Councillor David Renard of the Local Government Association. “Councils are facing significant funding challenges that will make monitoring and enforcing breaches of limits very challenging,” he said. To complicate things further, none of the new regulations applies to older appliances, nor do plans exist to enforce retrofits. So if a burner is giving out too much pollution, it doesn’t matter as long as it was made and installed before the new rules came into effect. It’s also not clear exactly when or how that will happen — there’s due to be a consultation before final decisions are made on the new limits.

Companies appear to be broadly unconcerned about the change, with many saying their products already meet the new tougher standards. “Our stoves already have no more than 3g of smoke per hour so this will not have an effect on our sales,” said Vicky Naylor, general manager at ACR Stoves, via email. New log burners are designed to ensure that the burning process is as thorough as possible, meaning the right amount of oxygen is introduced into the chamber and more particulates and pollutants are incinerated before they leave out of a chimney or flue.

SIA welcomed the move, saying a “large number of appliances in production” already meet the tougher standard. “Manufacturers are well placed to rise to the challenge of ensuring that all new appliances will comply,” the group said in a statement.

But campaigners and academics say this doesn’t go far enough, particularly as the rest of the economy moves to cars and heating sources powered by electricity. “We have no baseline for pollution health effects,” said Frank Kelly, a professor of community health and policy at Imperial College London. “We’ve got to go as low as we can, so that means we’ve got to stop burning things.”

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.