Nov 17, 2019

Aramco Sets Its Price and Defines Its Limits

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Saudi Arabia has accepted the reality that the initial public offering of its state oil company, Saudi Arabian Oil Co., won’t generate a trillion-dollar valuation beginning with “2.” Moreover, there is tacit acknowledgement that investors outside the kingdom think Aramco is worth even less than the $1.6 trillion to $1.7 trillion now sought. The transaction is going to fall short of its original ambitions, both strategic and financial.

The $100 billion gulf in the valuation range announced Sunday represents a 6% spread over the midpoint. This is tight for an IPO. Usually, when bankers set very narrow price ranges, it's because they think the shares will sell easily at a higher price and, therefore, perform strongly once listed. That assumption faces a severe test.

For overseas investors, it appears $1.5 trillion was their limit. Saudi Arabia may feel the company is worth more, and not want to give it away at what it thinks is too cut-rate a price to outsiders. But that is the reality of any IPO: A company is sold a bit cheaply, in return for the owner monetizing a stake and obtaining a liquid currency.

In any event, much of that conversation has now ended, with Aramco’s shares no longer marketed actively in North America. Hotels in Boston and New York should brace for a spate of cancellations. Sure, other international investors may yet be treated to the pitch, and qualifying overseas funds can still proactively buy in, or purchase the shares once listed. But the hurdles deterring them remain.

While Aramco generates more profit than any other company in the world, it is also the biggest producer of hydrocarbons, a sector from which investors have been running away. It is also impossible to treat the investment decision to buy Aramco as somehow unaffected by the fact that it’s controlled by the repressive Saudi regime. And, as with most national oil companies, there is a tension between market demands and political imperatives, with the latter usually winning. It is hard to see Aramco as being able to make big moves that aren’t in step with the wishes of the kingdom.

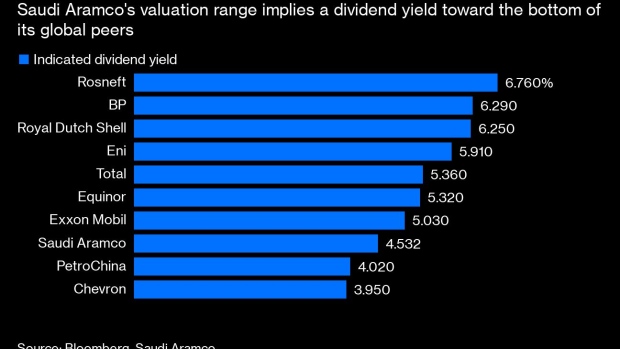

Meanwhile, Aramco offers a dividend yield below that of western oil majors like Exxon Mobil Corp. and Royal Dutch Shell Plc. True, those companies don’t have Aramco’s supercharged profitability. On the other hand, they don’t have to fund a country with their earnings.

The shortage of international interest means local demand, and passive buying by index funds, will have to do the heavy lifting. A retail offering of 0.5% with a further 1% institutional float must meet a total offer size of roughly $25 billion. That is a lot of orders to find. The free-float of Saudi Arabia’s local exchange, the Tadawul, is only $260 billion — less than Exxon’s market cap.

We are a long way from where this all started almost four years ago. The headline then was a possible $100 billion issue, comprising 5% of the company at a $2 trillion valuation endorsed by the world’s biggest fund managers. Now, selling about 1.5% for $25 billion at home, the risk is that the shares end up being highly illiquid once listed. They have been marketed almost like bonds, with guaranteed dividends and bonus shares for retail investors who hold on for six months. This may dampen selling pressure, but could lead fresh investors to sit tight until it’s clear where the price and volumes are settling.

Having failed to live up to the hype, it may have been embarrassing to pull Aramco’s debut. But a mainly Saudi transaction doesn’t help establish Aramco’s independent commercial identity. And if simply harvesting cash for Saudi’s sovereign wealth fund was the primary objective, cutting the price and finding more buyers would probably raise a bigger sum.

To contact the authors of this story: Chris Hughes at chughes89@bloomberg.netLiam Denning at ldenning1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Hughes is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals. He previously worked for Reuters Breakingviews, as well as the Financial Times and the Independent newspaper.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.