Aug 18, 2023

Detroit Carmakers Resist Pressure to Pay Up for Battery Workers

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- One of the more divisive topics putting General Motors Co., Ford Motor Co. and Stellantis NV at risk for potential strikes in the coming months concerns the thousands of battery workers they’ll need the next few years.

The United Auto Workers wants to represent these hires, and for them to get the same pay and benefits as union members at other facilities.

The companies want to cordon off this conversation from negotiations of new four-year labor contracts they’re negotiating with the UAW. For one, most of their battery factories are still under construction. Plus, these facilities aren’t the carmakers’ outright — each of them have set up joint ventures with Asian battery manufacturers.

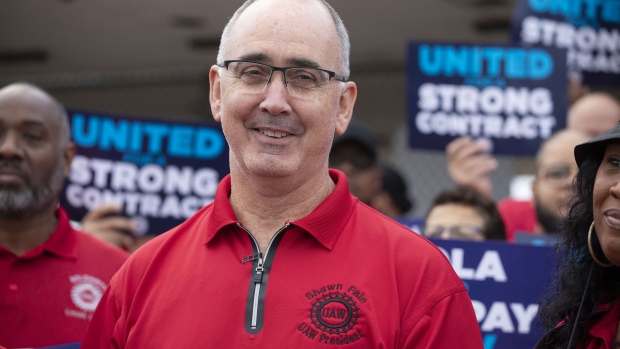

UAW President Shawn Fain understands carmakers needed to form joint ventures to access battery technology, but they could have hired the workers at better pay. He has a solution in mind: have the car companies do the hiring at auto-worker pay rates, then lease these staff to the battery ventures.

“We’d love to see it, or some type of arrangement, but the companies have to be willing to do it,” Fain said in an interview. “Their intent was to create a different class of workers.”

After making landmark concessions to the Detroit Three starting in 2007 — and getting just a pair of 3% raises over the past four years while auto profits soared — Fain is driving a hard bargain for his members. He’s sought a 46% wage increase, restoration of traditional pensions, cost-of-living increases, reduced work weeks and richer retiree benefits.

The demands would add more than $80 billion to each of the automakers’ labor costs, people familiar with the companies’ estimates have said.

Unhappy with what he described as too-slow progress toward a deal, Fain has called a strike-authorization vote next week. Results are expected Aug. 24, three weeks to the day before the UAW’s current agreements with the car companies are scheduled to expire.

The union sees the opening pay scale at Ultium — GM’s venture with LG Energy Solution in Ohio — as a threat to middle-class wages for factory work. Employees at Ultium start at $15.50 an hour, half the top wage at assembly plants.

The car companies say their joint ventures weren’t set up to be end runs around union wages. They need the expertise of battery partners to build the packs powering their EVs, and for these facilities to be cost-competitive.

“To me, that’s code for a race to the bottom,” Fain said. “Mary Barra made $200 million over the last nine years. I don’t know how someone looks themselves in the mirror knowing what they are doing at Ultium.”

Fain wants Ultium’s Ohio plant and all future battery factories to be included in the UAW’s national agreements, though he knows this will be tricky. He can’t bargain for workers who haven’t been hired.

There are other possibilities the union would be open to, Fain said, so long as battery workers are brought up to the UAW’s standard of compensation. The joint-venture employees could remain on the payroll of those companies, for example, but offer wages at or close to what the automakers pay.

Without better compensation, “the EV transition right now is not good for us,” Fain said.

Barra plans to launch a dozen new EVs, ranging from the Chevrolet Bolt that likely will sell for less than $30,000, to the Cadillac Celestiq priced like a Rolls-Royce. GM’s tagline for its electric-vehicle strategy is “Everybody In.”

Fain wants this line to apply to workers, too.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.