Apr 4, 2022

Diesel Crunch Gives Oil Refiners a Huge Incentive to Churn Crude

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- There’s a simple way Europe’s oil refiners can make more money right now: produce more diesel.

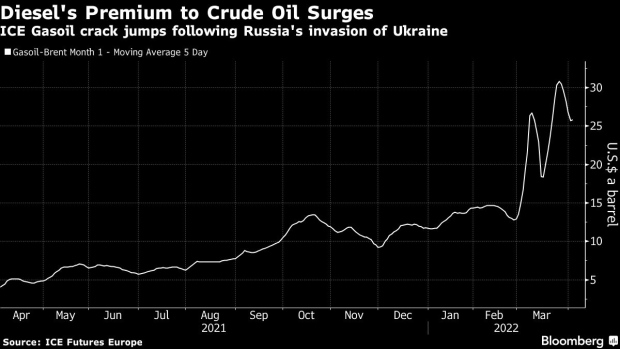

Profits from making the fuel have soared since Russia -- a key external supplier to the continent -- invaded Ukraine. Ensuing supply-chain chaos led to a massive price-surge that means diesel is far more expensive than crude almost six weeks after the attack began.

Diesel’s price rally, peaking in early March, has now abated somewhat but the fuel’s forward curve is still signaling an extremely tight market. How refineries respond to the supply crunch will help shape global petroleum flows, and could even influence the economic impact of the war, given diesel’s importance as an industrial fuel.

“There is a clear financial incentive to increase crude runs,” said Jonathan Leitch, an oil analyst at Turner, Mason & Co. “Diesel is leading the way in terms of products that are in short supply.”

See also: Hungarian Refiner Sees Massive Margin by Running Russian Crude

It’s hard to be sure that -- in practice -- European refineries really are ramping up their collective diesel output.

After the war began, many of them shunned Urals oil, Russia’s flagship grade, which in normal times makes up a significant chunk of Europe’s crude purchases. Alternatives exist, but there will likely now be more competition for them.

A number of Europe’s oil refineries are also undergoing maintenance, potentially weighing on any continent-wide increase in processing rates. Some have also closed since the start of the Covid pandemic.

“European refiners are sucking in West Texas Intermediate and drawing on short haul North Sea crudes to replace Urals spot barrels,” said Mark Williams, an oil products and refining analyst at Wood Mackenzie Ltd. “More Middle East crudes will need to clear to Europe as EU refiners back out of Urals.”

But running more crude oil isn’t the only way refiners can make more diesel. A plant’s output -- or yield -- can also be adjusted to maximize one fuel at the expense of others.

Williams said that price signals imply this is likely happening, even if there’s a lack of data to prove it.

There are also several uncertainties. High sulfur removal costs -- driven by high natural gas prices -- will limit how hard some refiners can push diesel-making units called hydrocrackers, he said. Non-Russian crudes may also not have the same diesel yield as Urals.

Oil refiners also only have so-much yield flexibility and so a significant increase in runs could well also result in more production of other petroleum products, like gasoline. Prices for the road fuel -- while historically high -- are already cheap relative to diesel.

“Benchmark gross refining margins are in double digits,” Williams said, adding that even after desulfurization costs of $5-$6 a barrel, there’s an economic incentive for higher runs.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.