Jan 23, 2023

Europe’s Biggest Pension Fund Issues Warning to Banks Over CO2

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- One of Europe’s biggest investors is putting banks on notice and may start exiting the sector unless it sees proof that claims of portfolio decarbonization are matched by action.

“The financial sector has really lagged,” said Dominique Dijkhuis, a member of the executive board and head of investments at ABP, which is Europe’s largest pension fund. “If you say you’re committing to a climate course and then still actively granting loans to new fossil products, that’s just not aligned.”

ABP is setting “transparent” key performance indicators that financial firms must meet in order to avoid being sold off in the next three years, she said in an interview. Banks need to “take responsibility,” which means looking “very critically” at their fossil-fuel exposures and “maybe move out.”

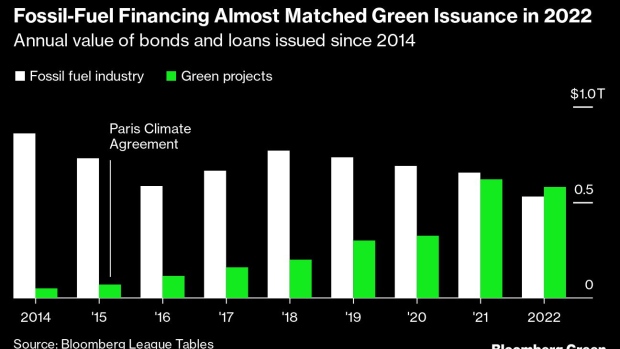

The remarks reflect a rapidly evolving landscape, as institutional investors, regulators, legislators and climate activists ramp up scrutiny of the finance industry’s role in fueling carbon emissions. That’s as banks making net-zero pledges continue to provide substantial support to oil, gas and coal firms that are expanding their business.

ABP made headlines in late 2021 when it announced it was divesting a €15 billion ($16.3 billion) portfolio of fossil-fuel assets. It’s now keen to cut its indirect exposure to high-carbon assets. “We’re concerned that the financial sector is still invested massively in fossil fuels,” Dijkhuis said.

The “majority” of the fund’s liquid fossil-fuel investments “are already sold” and whatever hasn’t been offloaded will be out of the portfolio by the end of this quarter, she said.

The climate risks lurking in the finance industry also have lawmakers and regulators concerned. Paul Tang, a member of the European Parliament, said it’s time to rethink bank capital rules to reflect the industry’s exposure to carbon emissions.

The Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs on which Tang sits is due to vote on new banking rules on Tuesday. He says support is mounting to require banks to add capital buffers if they don’t meet their transition targets. It’s a first step toward tightening the screws on the industry, which Tang is hopeful will win increasing support.

“If you have large exposures to fossil fuels or to emissions from fossil fuels, you need to have higher capital requirements,” he said in an interview.

Aurore Lalucq, a member Social Democrat member of the European Parliament, said failure to address the risks posed by stranded assets could leave taxpayers facing “a new financial crisis, just as devastating as the subprime crisis in 2008.”

“This is why we need to adjust banks’ capital requirements for fossil fuel exposures,” she said.

Global regulators are already warning that climate risk can’t be treated separately from financial risk. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision said in December that “climate-related financial risks can impact banks’ credit-risk exposure through their counterparties.” Banks should take a “conservative approach” to ensure capital reserves are sufficient to absorb potential losses, it said.

A key concern is the extent to which high-carbon bank assets become “stranded,” or worthless because they have no place in a low-carbon economy. A June report by the EU’s Economic Governance Support Unit that was sent to lawmakers said there’s now an “urgent” need to establish policy to deal with stranded assets.

The finance industry is fighting back. The European Banking Federation said in an emailed response to questions that imposing higher capital requirements for loans to the fossil-fuel industry will boost the price of capital and reduce the overall lending capacity of banks and won’t cut the demand for fossil-fuel activities.”

The EBF also said a climate capital buffer would push fossil-fuel financing into less regulated markets, which would create “competitive advantages for shadow banks and banks outside the EU.”

But climate researchers warn that inaction means lawmakers and the industry will have to deal with a much bigger problem further down the road. Finance Watch, a Brussels-based nonprofit, estimates that setting a minimum risk weight of 150% — which it judges is a realistic reflection of climate risk — on existing assets would require the world’s 60 biggest banks to add between $157 billion and $210 billion of capital. That’s roughly three to five months of their net income in 2021, it said in October.

Some lawmakers are even pushing for a higher capital requirement, of at least 1,250% for new projects.

Climate advocacy groups including ShareAction, Urgewald and Finance Watch say taxpayers may ultimately end up footing the bill of current failures to push through stricter climate finance regulations.

“The problem with climate risk is the longer you wait, the bigger the problem becomes,” said Benoît Lallemand, secretary general of Finance Watch.

In the meantime, institutional investors like Dijkhuis at ABP are stepping up the pressure. “We are going to engage with the financial sector on this topic,” she said. Banks can apply covenants to the loans they grant, so that makes it a “very conscious decision” whether they put their money in a fossil-fuel company or into a renewable energy business, she said.

--With assistance from Philip Tabuas.

(Adds ABP update on asset sales in sixth paragraph, lawmaker comment on risk weights in 17th)

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.