Jul 6, 2021

GOP-Led States Grab for More Control Over Election Disputes

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- New limits on who can vote and how in the U.S. drew the most attention as Republicans rewrote voting rules after losing the presidential election. But a subset of those bills threatens to expose the ballot counting itself to an unprecedented level of partisan politics.

In Georgia, Governor Brian Kemp signed a measure increasing state lawmakers’ control of the election board. Arkansas shifted oversight of complaints from county clerks and local prosecutors to a mostly Republican group of appointees. Iowa gave its elected secretary of state more oversight over county officials and created criminal punishments for infractions like failing to maintain voting lists properly.

The Republican push — such as curtailing mail-in voting — took on greater significance after the U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday upheld two Arizona voting restrictions, rejecting claims that they discriminate against racial minorities. The ruling put new limits on the reach of the Voting Rights Act, passed in 1965 during a segregated era, and may intensify the voting-rights battles fought out at the state level.

While determined voters may overcome restricted access to the polls, the oversight bills represent a more fundamental change: one that increases the likelihood that lawmakers caught up in fractious politics could sway election results.

“There is no question that we are seeing an increased risk,” said Derek Muller, a professor at the University of Iowa College of Law. “But it’s an open question about how it applies in the future.”

State lawmakers proposed more than 300 bills this year to restrict voting, according to the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law. Many were promoted as a way to build confidence in elections by combating voter fraud, a problem that in fact is surpassingly rare in the U.S.

“The result has been a number of bills and new laws that either take power or discretion away from local election officials or punish local election officials for inadvertent mistakes,” said Eliza Sweren-Becker, voting rights and elections counsel at the center. “That is really part and parcel of this overall effort to make it harder for Americans to vote and diminish protections.”

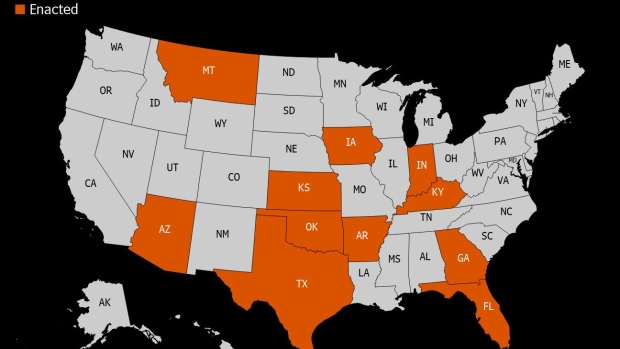

As of mid-June, state lawmakers had introduced at least 216 bills that would politicize, criminalize or interfere in aspects of election administration, according to States United Democracy Center, a bipartisan group that aims to advance fair voting. Two dozen have been enacted, a trend that “threatens the foundations of fair, professional, and non-partisan elections,” the group wrote in a memorandum.

Georgia, Iowa and Texas gave oversight to legislative or state officials while removing it from local counterparts. Kansas shifted authority to lawmakers from the executive and judicial branches — an example of a significant shift in electoral oversight. “American elections have historically been tremendously decentralized,” said Michael Morley, an associate professor at Florida State University College of Law.

Arkansas provides a stark example. In 2020, Democratic state Representative Ashley Hudson won in a 24-vote upset in Pulaski County. The results spurred lawsuits, and officials were found to have misplaced or mislabeled 327 ballots.

The district stretches across west Little Rock, a White, affluent suburban area that lies across a highway from predominantly Black neighborhoods. “It was one of those quintessential districts with a lot of wealthy, well-educated women,” said Janine Parry, a political science professor at the University of Arkansas.

Republicans have been losing ground in such areas; Hudson’s victory was the first for a Democrat in years. Earlier this year, the Republican-dominated legislature enacted over two dozen election-related laws including one requiring county election boards to refer written complaints to the State Board of Election Commissioners. That seven-member group includes appointees chosen by the governor, party chairs and ranking officials in the state’s House and Senate. Before, such complaints would’ve been sent to the county clerk and local prosecutors.

State Senator Mark Johnson, author of the bill, said it was necessary because elected officials like county clerks shouldn’t handle complaints that could help their party. “It is perfectly expected for legislators, when they receive complaints from constituents, to try to put together processes to clean that up,” Johnson said. “I don’t apologize for that at all.”

The state board, however, has only one Democrat.

And when the state board gets complaints, it now wields new tools for enforcement and punishment, thanks to a separate law drafted by state Senator Kim Hammer that lets the panel reprimand election officials, decertify them, seize their administrative duties and withhold funding.

The intervention was too much even for some of his party colleagues. “This bill goes too far,” Republican Governor Asa Hutchinson told the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. “The Legislature should not be investigating municipal and county elections.”

The bill became law without his signature.

The National Conference of State Legislatures, a lobbying group, noted the increasing state authority over local election officials in a June newsletter. The group said the trend has been 20 years in the making. The group highlighted pending bills in South Carolina and Alaska that would require suspected violations to be reported to the attorneys general. In Arizona, all voting irregularities would be reported to legislative leaders. A handful of Texas bills increases the secretary of state’s authority over voter registration.

After last week’s Supreme Court decision, voting-rights advocates said they will have to fight battles states to state, legislature to legislature, persuading voters and filing lawsuits. Others said the decision should encourage Democrats to renew their push to pass the For the People Act, which would set minimum state standards for voting.

North Carolina demonstrates the reason for alarm. For the past decade, Republicans, who control the legislature there, have consolidated power through redistricting and voting restrictions.

When the state Board of Elections, which is selected by the governor from nominees submitted by both parties, altered an absentee-ballot provision last year during Covid-19, Republican lawmakers saw that as overreach. They sought to limit the agency’s authority. Some board members resigned in protest.

This year, lawmakers used a state Senate budget bill to remove autonomy from the board that allowed it to act without legislative approval. The outlook for the $25.7 billion budget is unclear, as Democratic Governor Roy Cooper has veto power and Republicans may lack the votes to override.

Christopher Cooper, head of political science and public affairs at Western Carolina University in Cullowhee, said the state bill reflects the nationalization of all politics.

“It’s absolutely concerning to me,” Cooper said. “Partisanship is at the root of that battle.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.