Dec 9, 2020

Hedge Funds Love SPACs But You Should Watch Out

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Free lunches don’t last long in finance but hedge funds have identified a temporary exception to that rule: the special purpose acquisition company, or SPAC.

North American SPACs have raised almost $70 billion this year in initial public offerings, according to Bloomberg data, and a big chunk of that money comes from the hedge fund industry. Some funds hold scores of SPACs and it’s been a lucrative bet.

QuickTake: What’s a SPAC?

The central role of hedge funds in the SPAC boom is the subject of a new paper by Michael Klausner of Stanford Law School and Michael Ohlrogge of New York University School of Law, as well as this recent feature in Forbes.

In effect, hedge funds are providing bridge loans that have enabled a host of famous names from the world of business, finance and politics to launch their own SPACs this year. The funds are often arbitrageurs, though, with no intention of remaining investors once a SPAC has found a merger target. Retail investors and institutional investors who hold SPACs as long-term investments once a deal is struck haven’t always done as well.

It’s vital that these other investors understand that the lifecycle of a SPAC has these two distinct phases and that a hedge fund’s motivations for holding a SPAC often aren’t the same as those who buy later.

Ohlrogge and Klausner argue that the hedge funds’ profits come partly at these other shareholders’ expense. That’s all the more reason for retail investors to get to grips with how SPACs operate and for the finance industry to consider overhauling the way these complicated, costly cash shells are structured.

So which hedge funds are betting big on SPACs? Polar Asset Management Partners Inc., Davidson Kempner Capital Management and CNH Partners were among those with most capital invested in SPACs between 2010 and 2019, according to an analysis of regulatory filings that Ohlrogge shared with me. More recently Millennium Management, Magnetar Capital and Glazer Capital have led the pack, according to SPACresearch.com.

Lately, SPAC ownership has become a bit more diversified as wealthy family offices and sovereign wealth funds take stakes. Nevertheless, 10 hedge funds still own more than a quarter of all SPAC securities and the top 75 investment managers hold almost 70%.(3) What hasn’t changed is the hedge funds’ motivation for making these bets: They view SPACs as a fixed-income substitute with essentially no downside risk, and considerable upside potential. Here’s how the trade works:

The hedge funds make most of their profits if the shares jump when the sponsor announces a deal. That has happened a lot this year amid all the excitement about electric-vehicle companies.

This “pop” also boosts the value of the warrants hedge funds receive for tying up their money in a SPAC for a long period ahead of a deal.(6) That’s why it pays to back sponsors who are likely to find a good transaction. However, big name SPAC sponsors such as Michael Klein and Chamath Palihapitiya haven’t always been able to repeat their initial successes.

SPAC arbitrage has been frustrating at times over the past decade, hedge fund managers told me, but the flood of mergers this year and frothy valuations have made it very attractive. Annual returns on this trade averaged 8.4% between 2015 and 2019, according to SPACresearch.com. Ohlrogge and Klausner estimate an annualized 11.6% return for hedge funds that bought into the 47 SPACs that agreed mergers between January 2019 and June 2020 and then exited. Returns have probably gotten even better since then. In any event, the figures are stellar for an investment with essentially no risk of capital loss.

Until a merger is concluded SPAC investors always have the right to redeem their shares and receive back the cash they invested, plus interest; they get to keep the share warrants whatever they decide. Provided they don’t buy the SPAC for more than the value of its cash, don’t miss the redemption deadline and aren’t forced out of the trade by a margin call, hedge funds can be pretty confident of not losing money.

However, once SPAC shareholders approve a merger, they lose the right to redeem. The merged entity is now like any other publicly traded stock — the value can in theory fall to zero. The arbitrage crowd almost always makes for the door before this point.

This rush of hedge fund sales and redemptions forces sponsors to hit the road again to market the deal to asset managers more concerned by the target company’s long-term prospects and who’ll hold the shares post-merger.(5) If a deal isn’t exciting enough, the hedge funds might all decide to redeem, which drains the SPAC’s cash. Hence sponsors often need to raise a new pot of money from institutional investors at this point.

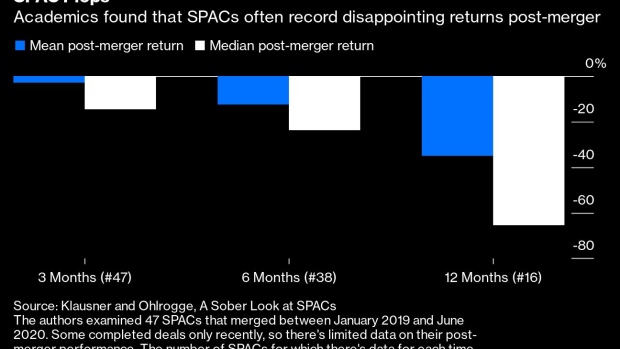

This isn’t an easy transition for SPAC sponsors and often the shares lose some fizz once the arbitrageurs move on. Ohlrogge and Klausner calculated their cohort of 2019-2020 SPACs recorded a negative 14.5% median return in the three months after the merger. Twelve months on the former SPACs they studied were typically performing even worse.

High redemptions, dilution caused by the free shares SPAC sponsors receive and dilution caused by share warrants (the ones hedge funds are given) might explain this post-merger malaise, Ohlrogge and Klausner say.

In fairness, most of this dilution should be apparent to shareholders at the time of the merger, as long as they’ve done their homework, and it can be overcome. Automotive technology companies such as Fisker Inc., Luminar Technologies Inc. and QuantumScape Corp. have soared after completing recent SPAC mergers. All are popular with retail investors keen to find the next Tesla Inc.

Meanwhile, some SPAC sponsors have started driving a harder bargain with the hedge funds by offering fewer dilutive warrants. If shareholders of Bill Ackman’s new SPAC, Pershing Square Tontine Holdings, decide to redeem their shares once it’s found a merger target, they’ll forfeit a chunk of the warrants to shareholders who stay loyal. Ackman is proud his SPAC has attracted “very few hedge funds,” which is ironic given he founded one.

While that might work for sponsors of Ackman’s caliber, most SPACs can’t afford to turn away a reliable source of cash. Indeed, some arbitrageurs say the recent flood of SPAC issuance has helped them negotiate even more generous terms.(2)

Perhaps the complex and circuitous way SPACs raise money needs a deeper rethink. Instead of raising money from hedge funds at the outset, Ohlrogge and Klausner recommend that sponsors search for a target to merge with first, and only then raise money from institutional investors and pursue a traditional IPO or direct listing.

This would save having to dish out warrants to hedge funds. The masters of the financial universe would have to look elsewhere for their free lunch.

(1) The SPACresearch.com analysis compared the value of SPAC holdings with the cash held in SPAC trust accounts. While not an exact measure of proportional SPAC ownership, it's a decent approximation.

(2) Warrants confer the right to purchase the stock at a certain level, which in the case of SPACs is typically $11.50 a share

(3) These can include hedge funds that aren't pursuing an arbitrage strategy or who elect to continue holding the stock because they like the deal.

(4) Either via higher warrant coverage or the sponsors putting more money into the trust account.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.