Oct 17, 2018

Know the law when you're common law

Presented by:

Is there a difference in your rights and responsibilities between common-law and married couples? You better find out before you shack up.

Gacie and Dave* moved in together during university. It wasn’t planned. Gracie was helping Dave get through an organic chemistry course and Dave was spending so much time at her place that, one thing led to another, and their tutoring relationship turned into a loving relationship.

The arrangement continued as they both graduated and went out into the working world. They went through internships, working contracts and bouts of unemployment. But after two years, when they both had stable jobs, Gracie wanted to know when they could get married — she didn’t want a huge wedding, but she wanted to make it official for her parents. Besides, Gracie was able to put down a down payment on a home — in her name only — and it needed to be filled with kitchenware, linen and everything else that wedding gifts could provide.

Although Dave wanted to be with Gracie for the rest of his life, he said he didn’t need the government to issue a certificate to ‘officially’ legalize their relationship. While it would never happen to them, he had seen too many lavish weddings result in the couples breaking up a short time later — “What’s the point?” Besides, he said, as individuals, there was more flexibility when reporting income tax as single people, instead of as a couple.

Gracie said he was wrong; there were more benefits to be had tax-wise as a couple. Plus, she said, once they have been living together as a couple, the law regarded them as married anyway. There are no real advantages, except saving the costs of a City Hall wedding and renting a tuxedo. (She thought Dave would look like 007 in a tuxedo.)

Unable to decide, Dave headed to his lawyer for advice while Gracie made appointment with her financial advisor.

Becoming common-law usually results in two people living together in a loving relationship without a certificate from City Hall. This represents about 21 per cent of all legal unions in Canada. But, many couples in this arrangement are often unclear what they are getting into from a legal or tax point of view. Nicole Ewing, a Tax and Estate and Business Succession Planner from TD Wealth helps us cut through these common misconceptions about what common-law means.

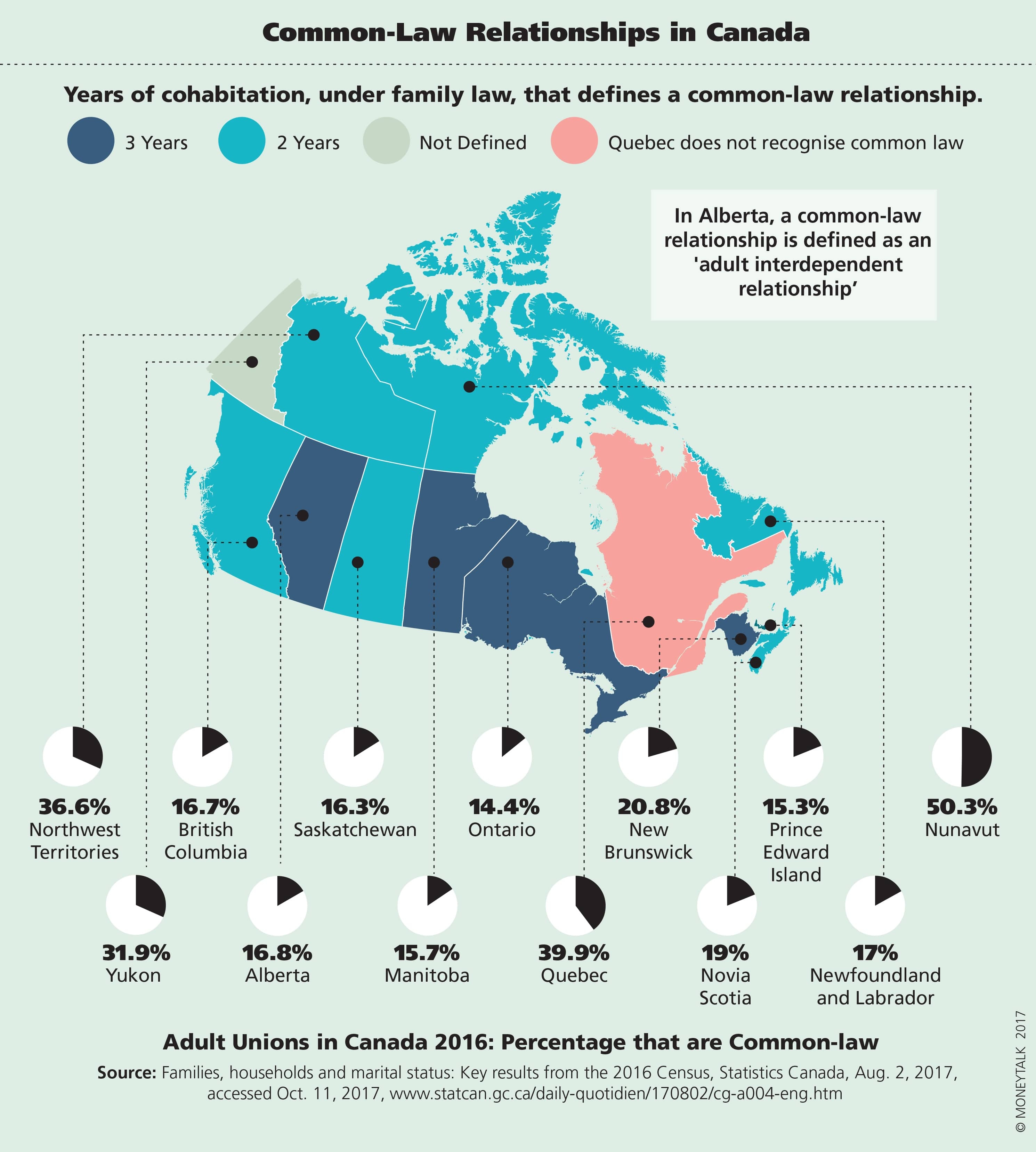

For many (but not all) purposes, the Canada Revenue Agency regards you as effectively the same as a married couple after one year of living together and you must report your common-law status on your tax return. But family and estate law regards you as common-law after two or three years (it varies from province to province — see chart, above).

Gracie and Dave are very much in love but they probably would want to understand where they would stand in case the unexpected happened and their relationship fell apart. And, if they do decide to remain common-law, they may want to make some other legal arrangements around their relationship.

21%: Canadians living in common-law unions, 2016. (Statistics Canada)

That’s because, if they break up as a common-law couple, having never been married, and depending on which province they live in, Dave may not have any claim to property rights in Gracie’s home. That is a big misconception many people have about being common-law: if the relationship ends, the individuals may have no claim on any of their ex’s property.

Dave could be left out in the cold even if he had contributed to the mortgage payments, paid for utilities, bought groceries, filled cars with gas and worked to renovate the house every weekend.

The reason is, a court would presume that if the common-law couple wanted to share property rights, they would have made a conscious decision to do so by creating joint ownership or naming a beneficiary in a will. Not doing so could well be regarded as a conscious decision by Gracie.

Dave does have options: he may seek recognition of something called a “constructive trust” with the courts which may address certain contributions made by one person which aren’t equitably divided based on the general rules. He would have to demonstrate to the court that he may be entitled to some compensation if he contributed to shared expenses throughout the years, because, for him, not to receive any compensation may be “unfair.” He could also argue that he contributed to the purchase of the home, even though his name was not on the deed of the home. But both these arguments could mean lengthy, expensive, and perhaps emotionally draining proceedings in court.

Ewing says that if the couple wants to stay common-law but also wants to ensure that neither of them would be left out in the cold if the relationship breaks down, a prenuptial or cohabitation agreement may be a good option. That way they could make arrangements to provide some kind of equitable division of their assets, and their obligations to each other, before they are common-law.

“A prenuptial agreement may also be an option for couples who are established and have a significant amount of assets.”

- NICOLE EWING, TAX AND ESTATE AND BUSINESS SUCCESSION PLANNER, TD WEALTH

However, one of the considerations about a prenuptial agreement is that both partners have to lay bare all their financial information and obligations. In this way, for example, if Gracie had creditors that Dave didn’t know about, and Dave had financial obligations to a child from a previous relationship, they would both have to share that information with each other. So while people wish to become partners in a loving relationship and be dedicated to working out a fair prenuptial agreement that would hold up in court, they must be prepared to bare all their financial details to each other.

Ewing says that a prenuptial agreement may also be an option for couples who are established and have a significant amount of assets and perhaps significant financial obligations outside the relationship.

For instance, let’s fast-forward 35 years and have Gracie meet Dave later in life; Gracie has a home, a vacation property and retirement savings at age 64 with two adult children from two previous marriages. If she wants to live common-law with her new love-interest, Dave, she may be unsure how her assets would be divvied up between her children and her new partner under various scenarios. Would she want Dave to share her assets after living together for a year? How about after ten years?

A prenuptial agreement may put her mind at ease, since she could make her intent known: for instance, one year into the relationship, she may wish Dave to have no access to any of her assets other than nominal payments for any money he contributed to the upkeep of her home during their relationship.

But, if Dave and Gracie live common-law for 15 years until Gracie passes away at 79, Dave may inherit and share the assets of Gracie’s estate with her adult children if Gracie makes those provisions in her will.

Note that if Gracie wants Dave to inherit part of her estate, she must spell that out in her will. Unlike a married couple, in most provinces, a common-law partner does not automatically have rights to property that is owned by the deceased partner. Again, for the same reasons mentioned above, even if the common-law couple were together for 50 years, an individual may not inherit anything if they are not named as a beneficiary in their deceased partner’s will.

Anyone who is considering or experiencing a major change in their relationship should consider speaking to a financial advisor and lawyer to see what the impact to their financial status will be and whether the change opens them up to any legal risk. While it may not seem romantic to be with your loved one at a lawyer’s office to sign documents, it could give you both some assurance that you are going into your relationship with your eyes open, having taken advice.

Were They “Married”?

A policeman, Joseph Chambers and a lawyer, Patricia Colleen Connor, began a secret relationship in 1993 although Chambers was married at the time. In court affidavits, Chambers said he and his wife and children spent long interludes apart over the years and eventually separated in 2012 but did not officially get divorced until 2015, several months after Patricia Connor died. Chambers and Connor continued their relationship throughout the years, seeing each other at least once a week, although they never married and never lived together. They also never co-owned property nor did they have a joint bank account. Connor identified herself as “single” on her tax returns and Chambers identified himself as “separated” after 2012. For the purposes of his group benefits with his insurance company, Chambers stated that he had no common-law spouse and he did not declare Connor as a beneficiary. Neither displayed photographs of each other in their respective residences.

But friends of the Chambers and Conner regarded them as a loving couple, who referred to themselves as ‘man’ and ‘wife’ and were seen kissing and holding hands in public. They socialized together, took numerous vacations together and helped each other out financially, with Connor declaring Chambers as her sole beneficiary on a sizable RSP. One friend of Connor’s said that Connor mentioned Chambers and an aunt would be the sole beneficiaries in her will. Although they did not live together, the court heard there was an impediment to the couple living together which the judge accepted.

When Connor passed away in 2015, her will could not be found and she thus died without a will (intestate). Five half-siblings, Connor’s father’s children by a subsequent marriage, claimed that they were heirs to Connor’s estate as she had no other living relative. But Chambers also claimed that, although they were never married, he should be regarded as having a common-law relationship with her and, therefore, was her heir.

After careful consideration of the evidence, Mr. Justice Kent of the Supreme Court of British Columbia, declared that the evidence that Chambers and Connor regarded themselves as husband and wife was overwhelming and that it was probable that Connor had made Chambers her heir in a will, a will that could not be found. He declared at the time of her death, in regard to her dying without a will, Mr. Chambers was the “spouse” of Ms. Connor.

*Gracie and Dave are fictitious