Jan 30, 2022

Myanmar Generals Face Spiraling Economy, Threat of New Sanctions

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Myanmar’s coup leader-turned-premier Min Aung Hlaing is grappling with an economy weakened by clashes with armed ethnic groups, foreign investors cutting ties and the threat of more U.S. sanctions as the junta enters its second year of government.

The aftermath of the Feb. 1 coup last year is putting at risk more than a decade of growth in the country, with the World Bank estimating the economy contracted by nearly a fifth in the last fiscal year. Myanmar’s economy might expand by just 1% in the current year to end-September, the bank has forecast.

While deposed civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi is in prison with more court verdicts to come, the generals are still doubling down with more air raids on rebel strongholds and suppressing protests that’s likely to weigh further on the economy.

“The arbitrary nature of the junta’s legal moves doesn’t bode well for investor confidence,” said Moe Thuzar, a fellow at Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. “The security situation in the country will also affect its economic potential and investor confidence, especially for infrastructure and related projects,” she added.

Here’s what the generals will have to contend with in the weeks and months to come:

Sanctions Threat

Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in December the U.S. is weighing new sanctions against the junta. Since the coup, sanctions have been leveled against individuals and entities tied to the regime and state-controlled oil and gas operations could well be the next target.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury this week issued a business advisory warning investors that state-owned enterprises, gems and precious metals, real-estate and construction projects are among the areas of “greatest concern” for providing economic resources to the junta.

Fewer Investors

TotalEnergies SE, Chevron Corp., and Woodside Petroleum Ltd. have publicly laid out plans to exit Myanmar in recent days, in a sign that sanctions might be around the corner for the oil and gas sector.

Despite the headlines of Western companies exiting Myanmar, approved foreign investments stood at $3.45 billion in the first 11 months after the coup, only slightly lower than $3.78 billion in the same period in 2020, according to government data.

That’s because companies from China and Japan have continued to invest with nearly $650 million flowing in since the military takeover, the data showed. However, these projects face a deteriorating business environment.

Closed Factories

Armed conflicts intensified last year, particularly in northern and central provinces that accounted for nearly 40% of Myanmar’s economic activity before the pandemic, according to a World Bank report on Myanmar published Jan. 26. Factories and businesses are either shut or operating at a far lower capacity thanks to limited staff, supply disruptions and weak demand.

Soaring Prices

A cash crunch in Myanmar’s economy was in part driven by a run on banks and then the junta limiting withdrawals and remittances, which in turn drove up the costs of food and petroleum. The Asian Development Bank has estimated that inflation rose 6.2% in the last fiscal year -- the highest in Southeast Asia.

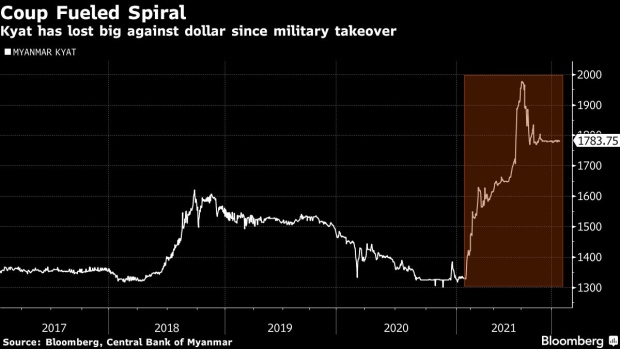

What has made it worse is the kyat plunging almost 50% against the U.S. dollar since the coup. While the currency has since stabilized, it is significantly weaker compared to pre-pandemic times and this has led to a surge in the cost of imports of fuel, cooking oil and construction equipment.

More Poverty

With rising joblessness and food staples becoming more expensive, a survey by the United Nations Development Programme published in December projected that nearly half of Myanmar’s 55 million population could be living below the national poverty line by early 2022. Some 27% of households in cities like Yangon and Mandalay reported selling a motorbike, a key mode of transport, to make ends meet, it added.

Blackouts, Shutdowns

Blackouts have become prevalent for businesses and homes following an output cut equal to 23% of the maximum national capacity. That’s due to parts of the national grid getting destroyed by rebel groups as well as temporary suspension of LNG-fired power plants due to hikes in gas prices.

The internet wasn’t spared either with the junta shutting down web access and social media to quell protests after the coup, costing the country $2.8 billion last year and forcing longterm investors like Telenor ASA to look at ways to exit its telco business. There have been increased charges on telecommunication activities and restrictions on access in recent months.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.