Oct 31, 2022

‘Nowhere to Hide’: Bond Managers Lag Benchmark in Rare Misfire

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Active bond managers are licking their wounds amid this year’s historic fixed-income rout and are banking on a big rebound in 2023 to show their worth.

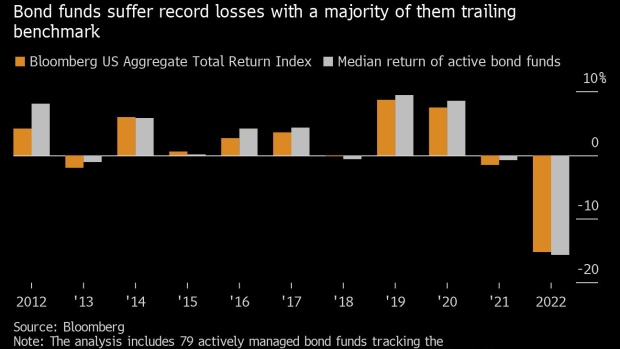

Roughly 60% of the funds pegged to Bloomberg’s flagship bond-market index have trailed the benchmark this year, the worst showing since 2018. That means most investors turning to bonds for a semblance of shelter from this year’s carnage in markets would have been better off in cheaper, passively managed index funds.

It’s a humbling display for active managers, who typically beat their benchmark by nimbly shifting between Treasuries, corporate debt, mortgages and asset-backed securities to tap the best opportunities. But 2022 has obliterated almost every corner of fixed income, with a punishing selloff fueled by aggressive Federal Reserve interest-rate hikes to tame stubbornly high inflation.

“There’s been nowhere to hide in 2022 and cash was king,” said Jack McIntyre, a portfolio manager at Brandywine Global Investment Management. “Clients don’t pay you to stay in cash for a long time.”

Active managers still dominate the US bond market, with assets totaling $3.6 trillion, up from $2.4 trillion in 2012, according to Morningstar Direct data. But index funds are growing rapidly: Their assets have surged more than 400% in that period to $1.9 trillion.

Inflection Point

The active crowd has reason to take heart as the market may finally be approaching an inflection point. Treasuries are coming off their first weekly gain since July, and softening growth is setting up a possible pivot in Fed policy that could give portfolio managers a chance to outshine their peers with sector calls and bond-picking skills. While officials are expected to deliver a fourth consecutive rate increase of 75 basis points on Wednesday, bets are mounting on a smaller boost at the central bank’s next meeting in December.

History is on the side of active managers. In the past decade, there have only been three other times when the median trailed the benchmark. In the two most recent instances, the next year brought redemption, with 70% or more outperforming the benchmark as the bond market snapped back with a stronger performance.

It would be hard to imagine a tougher environment than 2022. The 10-year yield peaked at 4.34% in October, the highest since 2007, from 1.5% at the start of the year, and the main Treasury index has tumbled 14%, dwarfing all prior annual declines.

“In the last 20 years, it’s been almost risk-free for bond fund investors,” said Russel Kinnel, director of manager research at Morningstar Research Services LLC. This year has been “a sobering reminder that bond funds of all stripes have risks.”

The preference of late is to allocate money to longer-dated bonds as the Fed’s inflation-fighting campaign increases the prospect of rate cuts starting next year. It’s an outlook that should generate price appreciation, reigniting the twin engines of fixed-income total returns. Bonds provide a regular income stream, while falling rates would drive price increases. This year, an income gain of roughly 1.3% in the main Treasury index has hardly offset a price decline of about 15%.

Surveys show investors have been adding interest-rate risk to their portfolios in a bet on lower long-term yields. JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s latest Treasury client poll was the most bullish in two years.

“We came into the year with zero Treasury exposure,” said David Giroux, who manages the $46 billion T. Rowe Price Capital Appreciation Fund. The fund, which invests in both stocks and bonds, has lost 12.8% this year, beating its benchmark. Giroux shifted money into five-year Treasuries around mid-year, then to the 10-year after its yield recently rose above 4%.

“One of the challenges for a lot of investors and not just bond managers is that they hug benchmarks,” he said. “We have always taken the attitude of going to where we see value and take advantage of what the market is giving us.”

Benchmark Pain

Sticking close to one’s benchmark has been painful this year, with markets slumping so deeply. But even managers with greater leeway in how much duration -- a measure of interest-rate sensitivity -- they can have were caught out by the inflation and rate shock.

“We have more flexibility than other managers but we didn’t take full advantage of that,” said McIntyre, noting his fund’s mandate allows him to reduce duration to 12 months. “We came in short duration at the start of the year, just not short enough. We could have run a one-year duration in our portfolios and weathered the storm better.”

The rationale for staying more exposed to bonds reflects the business model of active managers, who are supposed to navigate volatility adroitly.

Now that yields have soared, McIntyre’s fund is overweight duration in Treasuries relative to its benchmark as he expects a recession next year and falling inflation.

“Markets are very fluid and they are transitioning from a period when global central banks supported asset prices to one where they are being more supportive of the economy through restoring price stability,” said Arvind Narayanan, a senior portfolio manager and co-head of investment-grade credit at Vanguard Group Inc.

“This is an environment for active bond managers to find opportunities for their clients,” he said.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.